You are here

- Home

- blog_categories

- Inclusive Innovation and Development

- How can children in low- and middle-income contexts learn more easily when English is the medium of instruction?

How can children in low- and middle-income contexts learn more easily when English is the medium of instruction?

28 November 2017

There has been a strong push towards universal primary education. But can we make it easier for children to understand in lessons?

Across the world, governments give great importance to using English in classrooms as a language of instruction. They want to build young people’s intellectual and economic capital and to maximise their opportunities in an increasingly global world.

But there are strong arguments – backed by UNESCO and academic research – for education and learning to be conducted in a language spoken well by both learners and teachers. The mother tongue is often considered best.

How should education systems navigate these two important priorities to optimise children’s learning? It can seem like an impossible task, as these two ambitions may be unhelpfully positioned as opposites. It can seem particularly difficult in countries where English is rarely or never spoken at home and where there are many languages in use amongst the population.

Support for policy makers and practitioners

Our research project looks at how English as a medium of instruction currently operates in low and middle income (LMIC) contexts, and how the policies of governments, or of groups of schools, translate into practice in schools and classrooms. We have sought to provide insight and support to those responsible for setting policy or enacting it in complex language environments across the world.

The work involved collaboration between three complementary bodies, each of which brings particular insights. The research has been conducted by an Open University team which specialises in developing primary education and teaching in LMICs, notably in Africa and Asia. It’s been conceptualised and funded by Education Development Trust and British Council. Education Development Trust is a not-for-profit organisation that works with governments in many countries to improve educational outcomes for children. British Council trains and deploys English language teachers across the world.

Important time to rethink language in education

Why now? This project is driven by Goal 4 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. It calls on governments to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. Many nations have made great strides to secure universal access at least to primary and basic education. But there has been increasing concern among those trying to raise the inclusiveness and quality of learning, for example, in maths and literacy. They see that children are struggling to understand because of the language of instruction. Language can, for some, be a barrier rather than a route to learning.

Study design

To understand what’s going on, we started by reviewing over 75 relevant, high-quality international research publications focussing on language used in classrooms in low and middle income countries (LMICs). We paid particular attention to Ghana and India, countries in Africa and in Asia where we observed, on the ground, the realities of learning through English at primary school.

These two very different contexts provide valuable lessons that help policy makers, educators, teacher trainers and schools to navigate the complexities of multilingual EMI environments.

Ghana promotes an early exit, transitional bilingual education model, in which children are required to switch from learning through a government-supported Ghanaian language at the lower primary level to learning through English at the upper primary level.

India recommends that the state language be used as the medium of instruction in government schools: another modern Indian language and English are taught as curricular subjects. However, in response to dissatisfaction with the low-quality of government schools in India, low-cost private schools which use EMI are growing in popularity.

Different African and Asian EMI contexts

These two models represent two rather typical contexts in which EMI is used in primary education. In Sub-Saharan Africa, there is often a transition to EMI in government schools at the upper primary level. In South Asia and beyond EMI is increasingly being used in low-cost private schools.

The language-in-education policies in both these contexts have been fraught with difficulties in implementation. Evidence suggests that there continue to be difficulties in improving educational quality and this is in part related to language of instruction. This is hardly surprising: the majority of children have to learn the language of instruction while also learning curriculum content. This is bound to create challenges and contribute to low levels of achievement and progression through the education system in both contexts.

Our task in this project has been to identify these challenges and understand the opportunities offered within these English Medium contexts for improving learning amid the multilingual national settings.

Join the conversation

Over the forthcoming five blogs you will hear from the whole research team. The Open University researchers will set out the latest evidence from around world, alongside particular findings in Ghana and India. You will also hear from Education Development Trust on how the project’s findings should affect advice to policy makers and practitioners on making the most of multilingual opportunities in EMI contexts. The British Council will set out its thinking on the future of English in the classroom as it strives to support both learning and language in LMIC contexts.

We want to start a conversation about how best to use language (s) in the classroom in EMI contexts and look forward to you joining this conversation and contributing to this important debate. You can either do this on Twitter using the hashtag #EMIclassrooms or email us at ID-OU@open.ac.uk.

You can download the research report for free from The Open University: Multilingual classrooms: opportunities and challenges for English medium instruction in low and middle income contexts

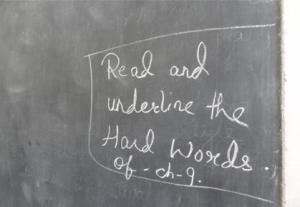

Photo by Dr Lina Adinolfi. Photo is not to be used without seeking permission from Dr Adinolfi.

Share this page:

Contact us

To find out more about our work, or to discuss a potential project, please contact:

International Development Research Office

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0)1908 858502

E: international-development-research@open.ac.uk

.jpg)