Sharing Stories for Children – Discovering the World’s Languages in One City

Tom Cheesman, curator of a fascinating new multilingual story sharing website, offers insights into how children’s tales opened up new worlds for Swansea locals under lockdown.

‘More Stories Swansea’ is a community art project, designed for pandemic conditions. Seed-funded by Swansea Council, the project aims to bring the city’s diverse local communities together, sharing languages and cultures across the internet and beyond.

We invite local people to record stories for children: fables and folk tales from their cultural traditions. They record on the phone and send in the audio files. We post the audio on our website (with a summary written in English and Welsh). Then, we invite local people to create illustrations and animations to go with the stories.

This game has a few simple rules. The participants must live in Swansea. They can tell a story in any language except English or Welsh, the official languages of Wales. Stories must be no more than 3 minutes long – the shorter the better. Stories and visual artworks must be suitable for children.

So far, we have posted 26 stories in a dozen different languages, plus half a dozen animated films and various other visual artworks. A mixtape of voices and visuals is on YouTube.

Zinia, a student beautician originally from Bangladesh, said at our first public Zoom meeting: “I was really happy to be involved in this project. It’s pandemic time, it’s really hard to cope. I have a five-year-old. And I really want people to know about my culture, how kids grow up there – I want to tell the differences. This is the best way to engage kids, they can see their story, see the differences, instead of feeling sad, when they can’t go out, can’t meet their friends. It was so fun!”

Zinia told her story, “The Cow Boy and the Tiger”, in Bangla (story #1 on our site). Dai Griffiths, a music student, turned it into an animated film. He researched Bangladeshi villages, houses, landscapes and breeds of cow: “It was really fun learning about the culture. As a westerner, it really opened my eyes to what else there is in the world.”

Dai did his own voiceover in English. But when artist and educator Lucy Donald animated Shahsavar Rahman’s story “The Lion and the Mouse”, she used Shahsavar’s voice, speaking Kurdish Sorani (story #19). Lucy and Shah met on Zoom to ensure that her animation fits the timing of his narration, and to discuss how her designs could best reflect Kurdish culture and make use of visual humour. “It’s a story I know really well,” Lucy said, “and it’s magical to hear it in a different language. Even without knowing any Sorani, I could hear the warmth and kindness in Shah’s voice, and that was really inspiring. You can hear the depth of Kurdish history within the spoken word.”

Shahsavar, a professional interpreter, said he believed storytelling has great power to change the world: “Stories can change how we relate to each other, change prejudices, change the politics of refugees, migration, integration. And they can change children’s minds.” He spoke of hearing stories from his grandparents and how they formed his character.

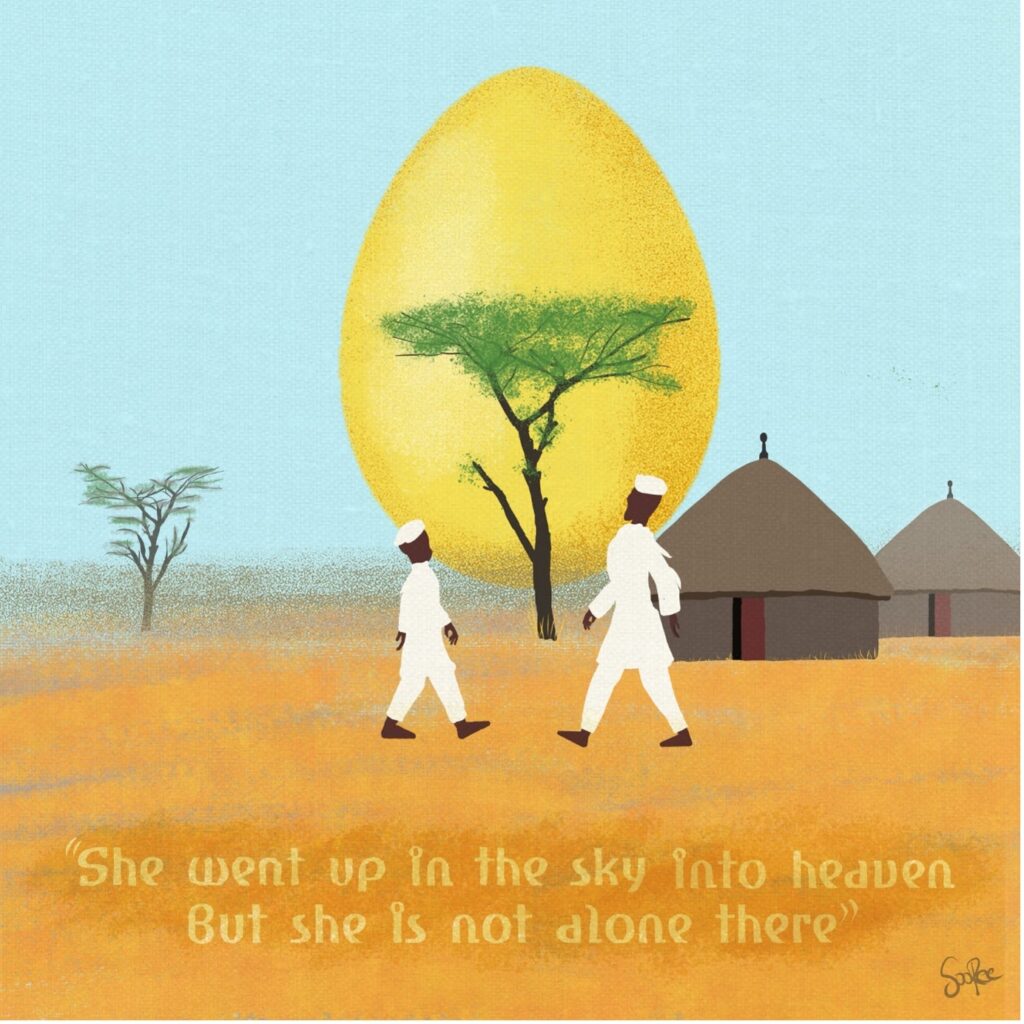

Million Woldemarian (a former flight safety engineer) explained how, when he was 8, his mother told him the story he recorded in Amharic (story #2). It’s a story about stories: about telling a story to comfort a grieving child. Million’s childhood friend had lost his mother; then Million’s mother told this story. A widowed father comforts his young son with the story that his mother is up there in heaven, with a hen which lays golden eggs, which she will send to us.

Such stories are much more than items of culture: they are intensely personal, emotional memories. Gwri Pennar, who created an illustration for Million’s story, commented that many of us can identify with it in these pandemic times of bereavement. Gwri researched Ethiopian landscapes, architecture and clothing, and created a powerful visual symbol of hope: the motherly golden egg rising like the sun.

The mythic image of the golden egg is found in many ancient cultures. Stories known in the West as ‘Aesop’s Fables’ never ‘belonged’ to Ancient Greece, they have always been told in many world languages. Cultural specifics are at the same time human universals. And each of these stories has an individual voice: an individual who lives here.

Other stories include startling witchcraft tales from the Congo in French, and from Piedmont in Italian; a story of the wise fool, the Sufi Nasreddin, told in Farsi; popular traditional lyrics from El Salvador and Guinea; micro-fiction from Uruguay; Chinese moral tales about the dignity of labour; a creation myth from Patagonia; and much more. Some visual artwork is by students, some by refugees.

Swansea People’s Multilingual Storytelling Audio Library keeps growing. We are talking to local schoolteachers about getting children recording (themselves or family members), translating, illustrating and animating. When lockdown eases, the project can be the focus of training around storytelling, digital technologies, languages, arts and cultural exchange.

There are 200 languages spoken in Swansea schools. There is plenty of scope to grow.

The project is owned by Hafan Books: ’hafan’ is ‘haven’ in Welsh. Since 2003 we have been publishing poetry, stories, drama and more by migrants and other local people, on behalf of Swansea Asylum Seekers Support.