A Book in a Crisis: Reflections on the Power of Reading

Professor of Twentieth-Century Literature at The Open University, Dr Sara Haslam, offers new ways of thinking about how, during the pandemic, books can both nourish and heal and how reading can be a vital act of curative self-determination in the face of oppression, confinement, illness and suffering.

The C-19 pandemic produced much comment in the early weeks and months on reading as emotional resistance/response to what was projected almost everywhere as a crisis on an international scale. Although some of that comment questioned, for understandable reasons, whether books could be any use at all given the scale of what faced communities (‘nobody wants a story when they cannot breathe’), or what place ‘comfort reading’ might have in a pandemic, this was pretty rare. And once the impact on the publishing industry became clear, what looked increasingly like a 2020 reading boom meant a proliferation of data for investigating further the relationship between reading and coping in a time of crisis.

Reading and well-being in times of high stress and enforced restriction

Researchers investigated, calibrated, discerned patterns in, the reading that populations were doing. Were readers needing to escape, to be distracted? Yes, was one clear answer, when you look at the numbers opting for crime novels and thrillers. But they were also looking for other routes to foster and protect their well-being in times of high stress and enforced restriction. Researchers in stakeholder professions such as education also began to pivot the research on physical and mental well-being under Covid towards reading as an activity closely tied to issues of social injustice and exclusion.

My work on literary caregiving attuned me to the power of reading to alleviate suffering, to create and foster social and emotional bonds – of the imagination or in real time and space – in the face of fragmentation and dislocation. Books both nourish and heal.

This understanding of reading is not new. Practices associated with bibliotherapy date back to the ancient world. But in 2021, training, career opportunities and organisations offer multiple ways of exploring related ideas given new impetus by the pandemic. The stakes are known to be high, and the language for expressing this is becoming more straightforward all the time:

Reading has saved my life, again and again

This tribute to the power of reading appears on the jacket of one pandemic-published book. An avid reader since childhood, Cathy Rentzenbrink notes in her introduction (p.3) that:

Reading built me and always has the power to put me back together again

Similar views about the power of reading, thanks to the internet, can be seen to be flourishing widely. And they are not just sustaining individuals, but are being built and held collectively also, in crisis, under siege, and as a response to poverty.

The relationship of books and reading to notions of agency and identity has quite a pedigree also. In my academic field, English Literature, one of the most famous depictions of reading as a vital act of curative self-determination in the face of oppression is more than 150 years old. Jane Eyre, that much loved and rebellious lonely orphan, finds enough strength in her focused engagement with a favourite book to fight back against her confinement and punishment in a loveless home.

Jane Eyre finds strength in a favourite book to fight back against her confinement and punishment in a loveless home

Books for the War-Wounded and Sick

Though I’ve worked on the Brontës’ fiction, in recent years my research has focused on the volunteer-led provision of books to sick and wounded soldiers during the course of the First World War. Women heading charities, like the War Library, or leading makeshift libraries, like the one at Endell Street Military Hospital, took pains to ease what was called a ‘book hunger’ at the time, affecting men ‘cut off’ from books that they loved, and from the books that helped them to express and enact their identity (Rhys 1916, 1000-1001).

The War Library offered a ‘personal touch’ in its operations, providing books the men asked for, and asking donating populations to give books they themselves cared for – such gifts would carry additional emotional freight and help to reconstruct social bonds.

In Endell Street, run by women with roots deep in the suffrage campaigns of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the library sought to cater to men with minds ‘full of horrors’, recognising that books offered comfort through familiarity and escape. Soldiers were encouraged to have no shame in their choices – whether or not they felt marginalised in class terms at the front there was freedom of expression in Endell Street. When they had recovered, they were free to return to borrow from the collection if they chose to, democratising access to books and perhaps improving their education and career potential at the same time.

An article published in The Times in 1915 advised the reading aloud of Jane Austen to the convalescent soldier.

All of her works were valuable, but the beginning should be Pride and Prejudice, the correspondent thought, as it was particularly ‘soothing to the pulse’ ‘What to Read to the Wounded, 20 April 1915, p. 6).

The Library of Daraya: Coping Under Siege in Syria

In Delphine Minoui’s recent book about the library of Daraya, formed under siege in Syria and precious beyond belief to those fighters and civilian populations left behind in the starving city, Pride and Prejudice was a first purchase for one of Minoui’s protagonists, post-siege in Istanbul. Her account draws out the passion for books imbued in the captive and largely underground population as they gather and then read and re-read the books that will form their library in a devastated city from 2013.

Cut off from loved ones, books become symbols of the future they hope to build, of the growth they can pursue in their minds – and of love.

The same survivor who buys Pride and Prejudice before their first Turkish meeting writes to Minoui about the books his finacée sends to him in lieu of physical contact. He’s not keen on the romances she favours, but considers a treasure Psychology and You, by Julia C. Berryman (in general self-help books are very popular titles in the Daraya library).

And yet what comes over more strongly still from her account is the collective endeavour that this library represents – and not just because of the lives that are risked in putting it together. Eager not to steal from the co-civilians who have had to leave their devastated city, the ‘book collectors’ led by Ahmad Muaddamani, Abu Malek al-Shami and Abu el-Ezz inscribe the texts with the addresses where they have been found, and/or owners’ names so that they can be reclaimed.

And there are ‘trends’, Minoui is surprised to point out, even in war conditions: there is much re-reading, for example, of Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, and Ibn Khaldun’s Kitab al Ibar [The Book of Lessons]. Other popular titles are Mustafa Khalifa’s semi-autobiographical The Shell, a ‘chilling… terrifying’ account of Khalifa’s 12 year detention in a desert prison in Palmyra (p. 49).

Titles like The Shell are thought to be essential by Daraya’s readers because they contain repressed knowledge. But the books of another writer, the Palestinian Mahmoud Darwish are deemed essential also: they are Ahmad’s ‘greatest comfort’ (p. 120). ‘I listen to these poems’, Ahmad says over yet another intermittent Skype connection to Minoui, ‘like you’d listen to a secret voice whispering things you’re unable to express’ (p. 121).

Daraya was evacuated in August 2016. Troops moved in and the library was pillaged for its books, later sold at Damascus flea markets by soldiers. But Ahmad’s siege history reading means that he does not think of this as an end.

The books of Daraya’s library, and all they represented, remain a source of nourishment and strength, and also fuel to a continued resistance based on the power of the written word.

Those reading about him surely must agree.

Reading and the Covid Chronicles project

The Covid Chronicles project has received copious testimonies from refugees and asylum seekers around the world that underscore the healing power of the arts and of especially of reading. In a blog We Need to Talk About Mental Health, the ways in which, under lockdown confinement, people turned to books for comfort and solace is described. We hope to do more follow-up research over the summer on the personal reflective journeys some readers embarked on, triggered by reading books like Elif Shafik’s The 40 Rules of Love. One Kurdish Iranian female refugee reader in her 60s described to us how, during lockdown, she used this book as a form of self-therapy to reflect on the many forms of love she has experienced in her life. Her meditations on love, life and loss that she shared with us were deep and poignant.

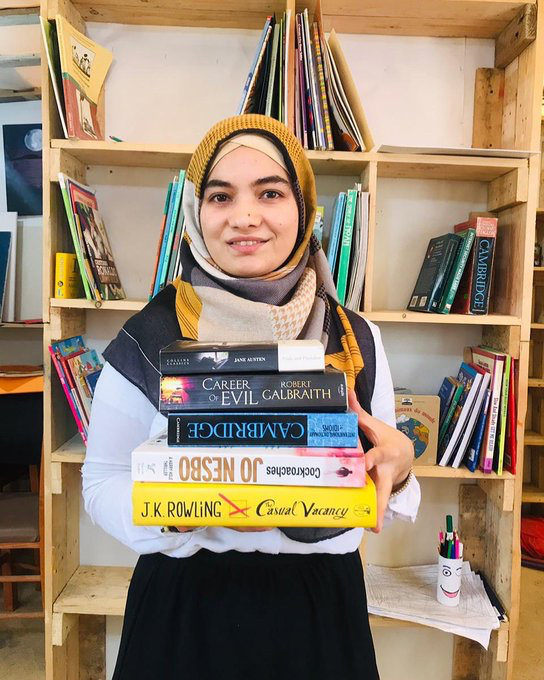

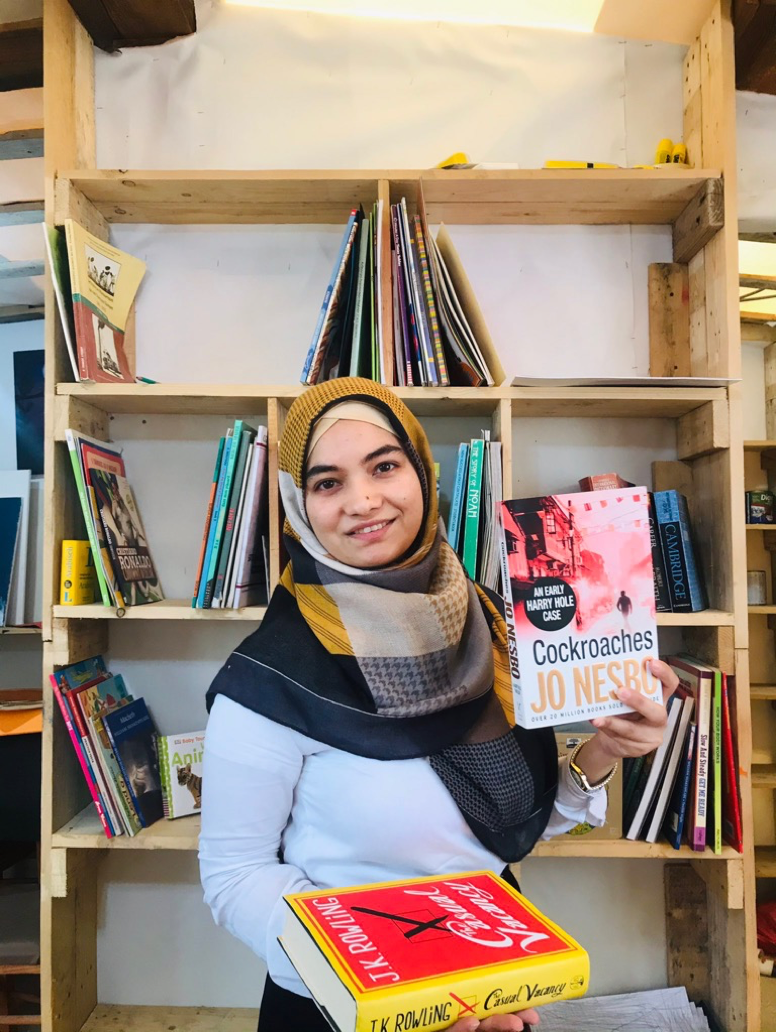

Another contributor to the project, Parwana Amiri, an 18-year-old Afghan refugee living in inhospitable conditions in Ritsona camp in Greece while awaiting processing of her family’s asylum claim, is a passionate advocate of refugee rights and education – and a book lover. She describes herself as a human’s right activist, author, poet and teacher and, even a cursory scan of her Twitter and Facebook accounts, reveals her deep love of books and reading. For #WorldBookDay @parwana_amiri wrote the following tweet:

I welcome you to my small library, constructed in my self-constructed class where I and some other teachers teach to residents of the camp. Thanks, dear Sonia and people in Poland for your nice donation to our school.

In an interview for the cov19chronicles project Pawana described how, as an avid reader, she taught herself English by reading books and how she imparts her love of books to the children in the camp who receive no formal education but are taught by herself and other volunteers. She expresses deep thanks to those who took time to donate books for her library and urges others to do similarly. Indeed, there are many book donation schemes for readers living in war-torn countries such as Books Aid International whose very raison d’etre is based on the belief that:

Books have the power to change lives

Their mission is to provide books, resources and training to support an environment in which reading for pleasure, study and lifelong learning can flourish.

My research has shown that many readers and book lovers make significant connections with their reading, across time and space. In the next stage of this work with the Covid Chronicles project, we hope to explore these connections in more depth. In the meantime, should you wish to read more about the vital role of Arts and Humanities in pandemic times, you might enjoy a series of thought-provoking blogs by our colleagues at The Open University.

Sara Haslam is Professor of Twentieth Century Literature at The Open University

If you have enjoyed reading this blog post please share by clicking the buttons below. Sharing will also help us get our message to more people.