You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 3 (2012)

- Christie Brown

Christie Brown

Christie Brown is an artist and Professor of Ceramics at the University of Westminster, London. In this interview, recorded in her studio on March 21st 2011, we talk about the influence of classical antiquity on her work, focussing on number of key pieces including the Cast of Characters (1995), Fragments of Narrative (2000) and Between the Dog and the Wolf (2003). Interview by Jessica Hughes. All images copyright of the artist.

- A PDF version of this interview is also available

JH. Thank you very much for agreeing to talk to me today. We’re going to be discussing some aspects of the influence that classical antiquity has had on your work. Perhaps you could start by telling us a bit about when you started working - how did you become an artist?

CB. Well, I didn’t start off as an artist – it was a second career. I was in my late twenties before I got involved in art. I had an academic, university life, and then I went to work in television for about five years. As a teenager I was a very romantic, creative, fantasy-laden girl – I loved the theatre, I loved art, but I think there was a creative bit of me that didn’t get going till later. I had the sort of family background which said “Art school? Drama school? You’re not doing that - you’re going to do something sensible!” So I did Drama and English and Greek Civilisation at university. I think I chose the Greek because all through my teens I was mad about Shakespeare, and through him I was mad about the Greek dramatists. I got very into Aeschylus and Euripides and Aristophanes, but particularly the dark dramas like Medea – I thought they were so heavy and romantic.

JH. Did you read them in translation?

CB. Oh yes. I was doing Latin at school, and I had this old teacher from Repton college who did want me to go on and study more – I think the fact that I even took an interest in Euripides was probably unusual! But no, it was much more to do with the fantastic stories of those plays and, well, I just always loved the Greek myths. I can’t pinpoint where I came across them – perhaps because I had older siblings – but somewhere along the line in my teens I came across those extraordinary stories about the fall of Troy, and Agamemnon and Clytemnestra (I remember wanting to have two Great Danes and to call them Agamemnon and Clytemnestra!) So when I went to university it seemed like the obvious subsidiary thing to do.

JH. So you came to the Classics through literature, rather than art and material culture, then?

CB. Yes, theatre really more than literature, because I’m not a brilliant reader. I’m always feeling guilty about all the books on my shelves that I’ve still got to read!

JH. Did you go to the theatre a lot?

CB. Yes, I lived not far from Stratford-Upon-Avon, so I went to the Royal Shakespeare theatre dozens and dozens of times all through my teen years, which is partly why I did drama at university. So that general cultural storytelling background was part of my growing-up life.

JH. And when did you first encounter the art of the ancient world? I see that you’ve got a copy of Greek Art on the side here…

CB. My old copy of Greek Art, by John Boardman. Yes, every line is underlined really – this is how to get through exams, more years ago than I care to remember!

JH. Was that at university?

CB. It was at university, yes. I seem to remember that Greeks Civs, as we called it, was divided up between Greek theatre, Greek pottery and sculpture, and something else, maybe politics, I don’t know…but certainly it was the sculpture and the pottery that drew me in, and the theatre of course. We did plays – big productions of things like Sartre’s Flies, which is the story of Electra, and we did a production of Medea in the drama studio, and I loved being involved in all of that sort of stuff. It’s very melodramatic in a way, but I just thought it was marvellous. But it was much more an involvement with narrative and theatre than it was with visual culture, because I really didn’t know about contemporary art. I mean, I knew about sculpture a bit – I knew who Rodin was, but it was through the theatre and the storytelling that I got involved with all that. The objects and art came later. But it meant that when I did finally get involved with art practice, I went straight back to the classical and archaic forms of sculpture. And that really underlies everything that I do – it’s an involvement with, not just the classical, but with the archaic, the pre-classical, the Egyptian and so on…those are the cultures which have really drawn me, and of course, as a result of that, the Renaissance, which as you know was feeding off the classical. So when I started to make ceramics, and then moved from pottery into sculptural ceramics, I just headed straight back for those kinds of images to inform the figurative work I was doing.

JH. And the narratives of classical myth have played a big part in your work. Was that right from the beginning of your practice? Can you remember your first piece that was influenced by classical images or ideas?

CB. Not really. Now I look back and I see all the connections – storytelling and theatre and so on, but I don’t think I was conscious of that then. In my early work, which was very lyrical, decorative and flat, it was to do with a fascination with line drawings, and a gap between fantasy and reality – these were like pieces of relief that had stepped off the wall. So the reference was a formal one rather than a narrative one. It was all about idealisation – that gap between fantasy and reality, which I saw as paralleled in our own contemporary obsession with the beautiful body. And so I played that connection between the classical Greek and Renaissance statues (Cellini and people like that) into contemporary advertising and photography. All that early work comes out of this kind of mix rather than the narratives. They tend to emerge a bit later.

JH. You can definitely see the classical forms in your early work.

CB. Yes definitely, it was all that period. You can see the contrapposto pose there.... It is very much based on this sense of an idealisation, of a sensuous body and so on. It was very successful in terms of getting me established because there is a certain beauty about them

JH. They are beautiful, and they are fragmentary, which I find interesting.

Red Lynette Reclining, 1990, Ceramic, 74 x 64 x 13 cm.

CB. Yes, they are sort of partial. But you know, all those ideas were not very well considered. I went through a two-year vocational ceramics training, which was really about making pottery, and I came out as a figurative sculptor, but the amount of theory or information was very limited. The course I teach now is a three-year BA and we’re very hot on asking the students “Why are you doing this?”, “What’s the context you’re doing it in?”, and so on. But people weren’t in 1980: they just said “Oh, that’s pretty”. And so what I looked at was either life drawing or contemporary photography or ancient Greek statues.

Moving on from there, after the flat figures I wanted to keep working with slabs, but I wanted them to be more three-dimensional, and I wanted them to have heads.

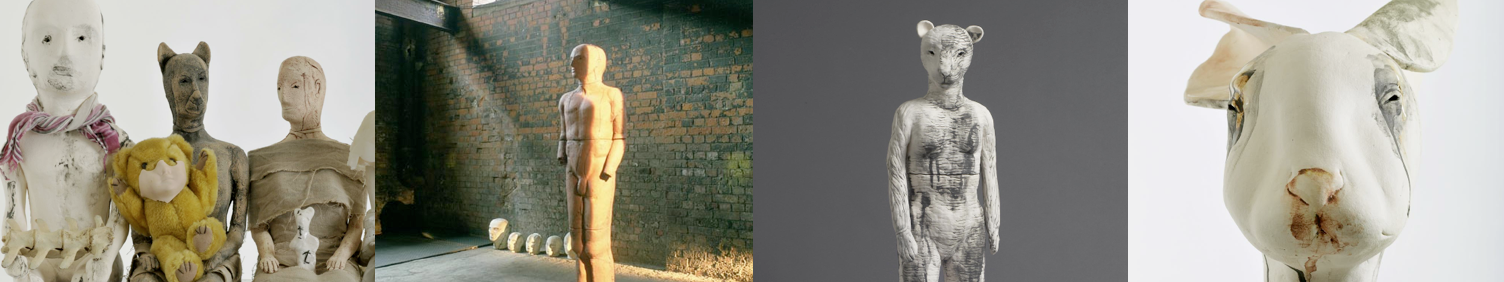

Figures from The Cast of Characters, 1995, Ceramic. L to R: Sleeping Automaton (4 x 39 x 18 cm), Ghostly Lover 2 (74 x 36 x 18 cm), The Living Dead (both 70 x 33 x 18 cm).

This little group is called The Cast of Characters, and these represent ‘archetypal’ ideas. In fact, the formal pose is much more to do with archaic forms than classical. Here I stopped with the contrapposto and instead I gave these figures a very static, rigid pose. And that took me into a whole world of metaphor about the mould, and how we are cast in the same mould – how we’re the same but different.

JH. Who are The Cast of Characters? Do they have their own individual identities?

CB. Yes, this one is called Automaton, for instance. There are about six automata, and this one is part of a series called The Ghostly Lover. This is another pair of twins, called The Living Dead, and then there was another pair of twins called the Delphic Twins, which was about narcissism, and knowing yourself.

JH.The Delphic Twins is an ancient statue, isn’t it?

CB. Yes it is, and the ‘Know Thyself’ motto is written over the Delphic Oracle. I was in psychoanalysis myself, which is all about finding out about who you are, and making your own life better in order to make other peoples’ lives better. So this ‘Know Thyself’ motto that was written over the Delphi temple was a key issue. And these figures just look at each another – they are absolutely fixed on each other.

JH. That’s a fascinating connection to make between the Delphic Motto and the Delphic Twins. Are they made from the same mould?

CB. Yes, and the whole series were made from only three or four different moulds. Here’s the Stone Mother, and the Child of Glass.

The Delphic Twins, 1995, both 73 x 38 x 19 cm.

JH. Are these other figures drawn from psychoanalysis too?

CB. Yes, they are drawn from Jungian theory about archetypes, rather than Freudian. Freud didn’t invent the concept of the archetype – that’s a Jungian idea, that we all have these archetypal people within us, so for instance Muses, wise old people, sexy young people…. These are my own archetypes, not anyone else’s. It was an intensely personal piece of work. And this group, as well as taking me down a more three-dimensional route, got me using big moulds, which brings me onto the show at the Wapping Power Station.

JH. So this was the one commissioned by the Women’s Playhouse Trust?

CB. Yes. The Women’s Playhouse Trust was a feminist theatre company in the seventies, run by an extraordinary, dynamic woman called Jules Wright, who still runs the Wapping Project. She had found this amazing building, and originally I think that she probably saw it as a potential theatre. But the acoustics are terrible, and so she’s never really been able to use it as a theatre, although she does have dance performances there. So this meant that she shifted her focus and started to put art exhibitions and big projects like that (there’s also a beautiful restaurant there). She bought some of my early work and she really liked it, and then she saw the Cast of Characters in a show and asked if I would like to go and visit the Power Station. It was a huge project – to make a group of work in response to this space, which had a sort of Romanesque church feel to it, very high, with high windows on either side. It was the first time anyone had asked me to make group of works in response to a particular place, and there were lots of things to respond to…formal things like the colour of the building, the red bricks and white tiles, which were the sorts of colours I’d been working with anyway - but also the fact that it had been a power station. So I decided I was going to make this group of figures about myths of origin.

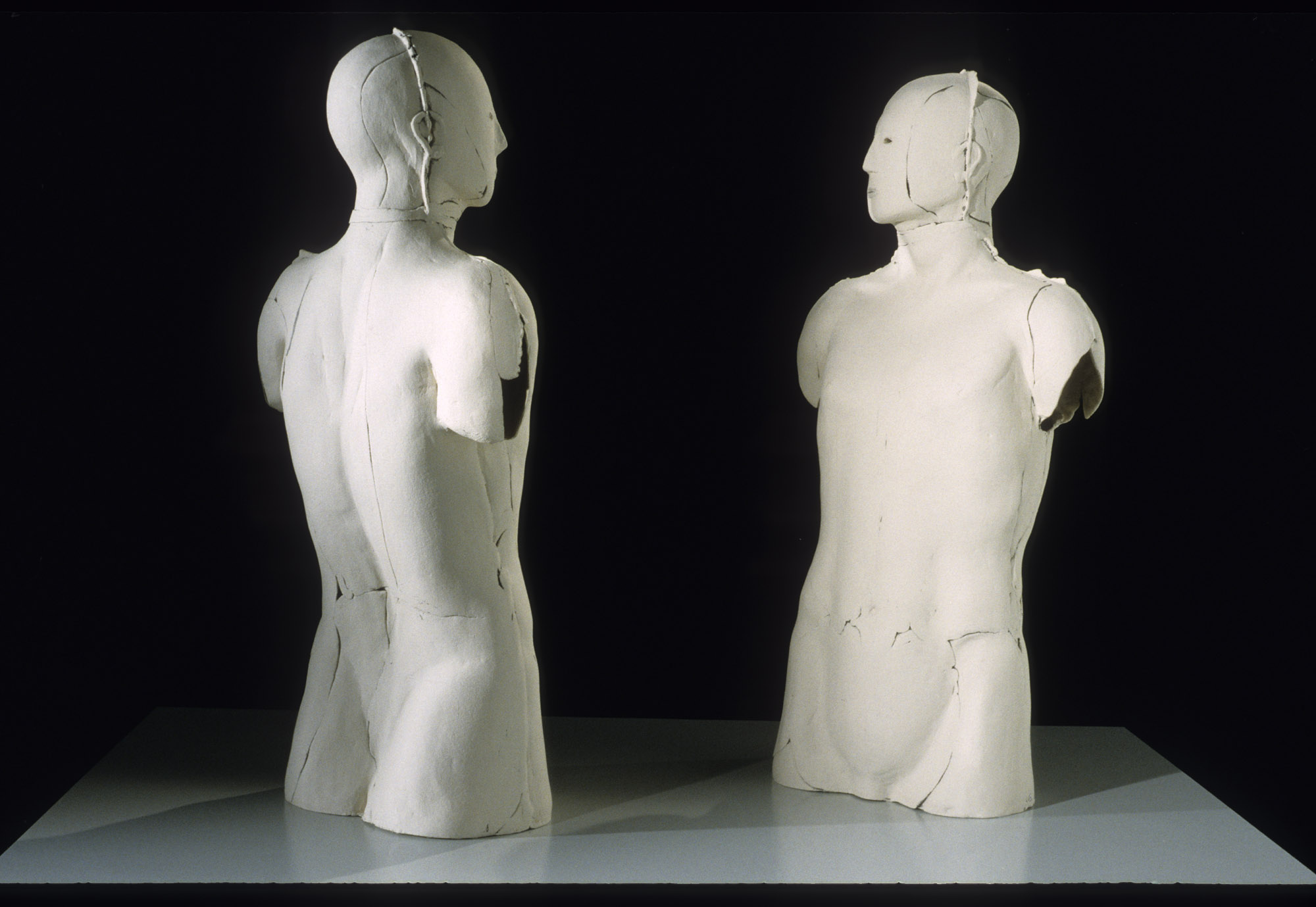

Fragments of Narrative, Installation shot, Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, 2000.

That’s the main space [pictured above], and then there are two little rooms at the back. I put big figures in the little rooms, and then little figures in the big room, which somehow made it even bigger than it was, like a marketplace with people walking in and out of it.

JH. And classical myth played a big part in this exhibition?

Prometheus, 1998/9, Brick Clay, 168 x 43 x 36 cm.

CB. Yes. So this is Prometheus. I had this idea – because it was a power station – this idea about animating, bringing things to life, so I was focusing on these characters. This is the myth about Prometheus making human beings out of clay, before the goddess Athena breathed life into them. So that’s my Prometheus, and this group on the left is Pygmalion and Galatea – she’s looking a bit desperate! And this one on the right is Olympia, a big puppet doll from Hoffman’s Tales. There are all kinds of animated beings here. All of those myths are about transgressive behaviour, aren’t they? It’s down to gods to create human life, it’s not down to us…and I just find all that edgy ‘in-betweenness’ quite interesting. And I love that story of Pygmalion and Galatea. It’s such a crazy story really, isn’t it?

Red Pygmalion and White Galatea. Installation shot, Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, 2000.

JH. It really is, and that is such an interesting interpretation of it. Did you use Ovid as your source?

CB. Well, I knew the story anyway. I seem to feel that I know the stories very well, without being very clear on when I read them. I must had some early Greek myths books when I was a kid, because I knew a lot of the stories – they were really sort of ‘instilled’ in my brain. I don’t think I read original Ovid until quite recently, and even then I hadn’t read the whole thing. But I did read Ted Hughes’ translations.

JH. So when you first thought of making a Pygmalion piece, it wasn’t the case that you then went to the text and read through bits…it came more from your implicit memories of the story?

CB. Well, I just knew there was this story of him creating this idealised woman, you know. And you see, that all keys into other things to do with the early work, like when I’m dealing with idealisation, and with how people need power and control in relationships, and so they idealise their partners, or put them on pedestals. This is the perfect story for people engaged with those ideas - Pygmalion couldn’t cope with real women out on the street, so he had to make own statue that he had total control over.

JH. She is white - is that a reflection of her being ivory in the story?

CB. Yes, although she is made out of white clay. I worked in the two colours, which is partly because of the building, which is full of these white tiles and red bricks. So the red figures were made out of brick clay, which is quite coarse and rough, and the white figures were always made out of a white clay which is like all this stuff (gestures to the other works in the studio). I haven’t got a close-up of her face…

JH. They are quite android-like, in a way - quite futuristic.

CB. Yes, they are. Well you know, if the beginning is the Prometheus-type myths, it comes right through into Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and the Golem, and then right through to Bladerunner and I, Robot…. It’s all about the slightly transgressive creation of life. I just happened to tune into I, Robot the other day for five minutes, and I thought ‘Oh my goodness!’ Forty thousand robots, and one of them is this rogue one, and his eyes move suddenly – and I thought ‘Well it’s the same old story - you make something, and then it turns against you if you’re not careful’.

JH. Can you say a bit about how the figures in this Pygmalion installation are positioned, and their relationship to the story. Why are they so far apart? There doesn’t seem to be any interaction between them.

CB. Well there is a kind of interaction. He is looking at her a bit more than is apparent in that photo. I think I was also very conscious of trying to create a dynamic space with sculpture. There are always two things going on, aren’t there? There’s kind of a narrative thing, and there’s a spatial, formal thing.

JH. So is he stepping back to admire his handiwork? What point in the myth are we at? Or can you not tie it down so specifically?

CB. Not really, no.

JH. And this Olympia - what’s her story?

CB. She’s a broken doll. She’s another kind of Pygmalionesque character, in that she’s been created by a puppet-maker and she’s idealised and beautiful. She’s an automaton, a full-sized automaton. And a young man comes to the Puppet-Master’s shop, sees this beautiful dancer, and she dances for him. He takes her away, but then he realises she’s just a doll, and not a real person, and so he breaks her up.

JH. So it’s almost the opposite, then, of Galatea?

CB. Absolutely. It is the opposite of Galatea. I remember the tales of Hoffman when I was a child, giving me bad dreams! But also Pygmalion and Galatea, without even reading Ovid...you know, when I was a kid, my father loved My Fair Lady, which is based on Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. Those themes run through so many things, don’t they? They’re archetypal stories.

JH. Going back to Prometheus, I remember reading that you included a helper figure in the Prometheus story? Where does that come from?

CB. Yes, well…these are all the helpers (shows image). This is Prometheus’ helper in the centre, but all the others are helpers as well – they’re Galatea’s helpers, and Pygmalion’s helpers.

JH. But those characters are in the little rooms, so they’re not placed together with their helpers?

CB. No, the helpers are in the big space. I couldn’t specifically say why they’re not with their ‘masters’ and ‘mistresses’, if you like, or why they’re doing their own thing. They are based on the Egyptian concept of Shabti. That’s the idea that you have got to take something with you into the next life to do all the chores, like the ploughing of the fields and growing the crops and harvesting the crops to have food. In a way, these tricky characters are all Shabti figures.

JH. So you’ve taken an element of Egyptian culture and mixed it into the classical myth.

CB. Yes, it’s a totally eclectic mix. I draw on whatever I like. It tends to have an ancient feel to it, but it could come from any culture, really. But it is about cultures that have got a lot of stories connected with them, and Egypt is a very powerful one.

JH. What does Prometheus’ helper have with him?

CB. Those are the yarrow stalks that he steals the fire with. And this figure is Athena. In terms of the narrative, it wasn’t so specific that you could say, “oh well she’s talking to him”, or say why she’s standing next to him, but I just liked standing these big figures in this small space.

JH. It must have been amazing to walk round that space and encounter figures from different narratives that are all mixed up…you know, going into one room and seeing Prometheus and then Athena, and maybe if you know the myth you’d say “Ah, that’s funny, they’re going to meet eventually!”

CB. Yes, I wonder how many people really knew the myth. They knew the titles, but that would be interesting to find out. I never asked anyone ‘What does the word Prometheus mean to you?’

JH. Well, they’re very evocative words even if you don’t know the actual line-by-line story.

Golem, 1998, Brick Clay, 186 x 48 x 37 cm

CB. Yes. I’m sure a lot of people would be aware of some of those stories. And of course that’s why the Golem is here, not because he connects in a timeline, because he doesn’t. But because like Olympia he’s yet another story of a transgressive creature made of clay who turns against his master in the end. He was made by a fifteenth-century Czech Rabbi in Prague, and as a protection against pogroms, and so he’s a very famous Jewish myth. He’s this protector, a big clay man that you bring to life by – well there are various ways, but the main one is that you write the name of God on a piece of paper and you put it in his mouth.

JH. Is that why he’s lying down?

CB. Yes, he’s not been animated yet. He’s waiting to wake up.

Resource, 1998/9, Brick Clay.

And here we have the first reference to ex-votos, in the same show. And it was very much inspired by that sense of…well, there are lots of themes to this piece. It was inspired formally and structurally by seeing ex-votos in Italian churches. I have a Brazilian friend who goes back to Brazil a lot, and she’s always bringing me ex-votos in wax and wood. So that was how the formality of them came along. But all the torsos are all from the old moulds that are no longer used - they’re all from Cast of Characters moulds. It was such a big room and I really wanted to do a big wall piece. It was called Resource, like Human Resources, so it’s a bit of a tribute to the people who used to work there. But there’s also that idea that you gain knowledge from ancient fragments, which of course is how the art academies all started. You know, you had to draw ancient Greek fragments repeatedly, and that’s how you learnt to be a great artist.

It was really after the Wapping show that I got into academia, and academia obliges you to think – I mean, it’s very positive in that way - it obliges you to think about what you are doing more.

JH. When you say you got into academia, what do you mean? Did you go back to studying?

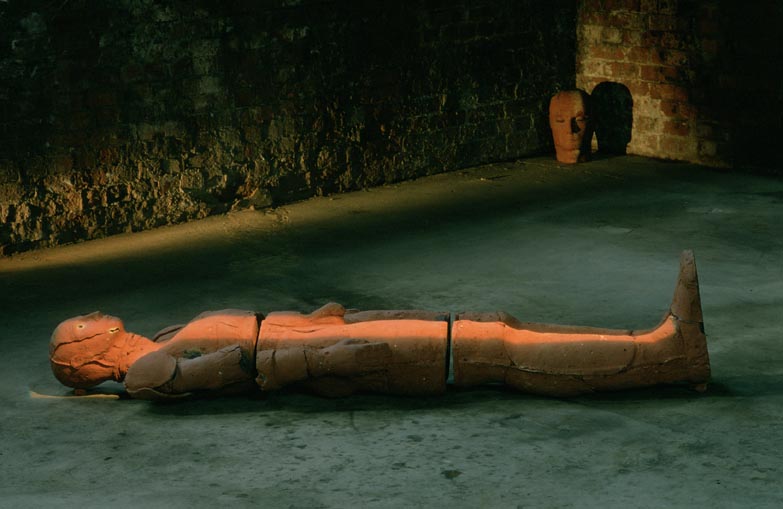

CB. No, I was working in academia and I was teaching in the Ceramics department from about 1993, but it wasn’t really until the Fragments of Narrative show in the Power Station that I became part of the research culture, and people would say “Can you write about this” and “What’s this about?” and so on and so forth. So I got a bit of a sabbatical in 2003, and that’s when I started to make this series called Between the Dog and Wolf, and out of this came the idea of exploring change and metamorphosis. Sometimes you get inspiration from curious places, so I was in a French garden in twilight, and my French friend said C’est entre chien et loup, and I just thought it was such a wonderful phrase to capture. You know, it was this beautiful summer evening, and the bats were beginning to fly in the sky, which was still that deep blue, and you could still see the black trees but it wasn’t quite dark.

Entre Chien et Loup, 2004, Ceramic and Mixed Media (dimensions variable)

JH. Is that a common idiom in French?

CB. Yes it is – Between the Dog and the Wolf. So it’s that lovely sense of – you know, you’ve got the tame daylight doggie and this wild wolf. That was the inspiration behind this group (shows image), and that’s where the human-animal hybrid first began to kind of peek out.

JH. These figures look quite different from classical hybrids, don’t they? The type of animals that you’ve chosen - they’re kind of ambivalent, in terms of identifying what they are.

CB. Oh yes, they’re not very clear at all. I think she’s (points to one of the figures) probably the clearest because she’s got a kind of cow’s nose and tail. But this one’s got a sort of cat head and then these slightly spiky wings, and she’s got a mix of bird beak and then these net wings, and then white arms, and some have little claw feet. It was a very much more an intuitive way of creating. It’s the same mould, same figure, but she’s just sprouting all these different bits and pieces.

JH. Is there any significance in fact that they’re all female?

CB. Yes I think so. I’d made lot of male figures in the Wapping show, and just thought it was time. Sometimes you just work quite intuitively, and I’d seen some very beautiful figure in Brooklyn museum, which was very static, but quite feminine. And then I got this Between the Dog and the Wolf idea. It was a time of transition, and I was exploring that idea about transition and change, and also I was trying to broaden where I showed the work. Because if you come out of ceramics it’s very easy to get stuck in a small-scale ‘objects on a plinth’ kind of thing.

The last piece I’ve got to show you is this - the full piece of Ex-Votos, which was also part of Between the Dog and Wolf. This one for me is a really important piece, because it’s got this mix of archaeological dig and a burial site. The heads are two moulds, one male and one female, so it’s sort of all humanity. And their heads are full of shards – they’re not just spilling out, they’re right inside the heads, these objects of memory and history.

Ex-Votos, Brick clay, 2003-2004 dimensions variable

JH. And that work is called Ex-votos? Did you actually conceive of these as ex-voto offerings, or is just that the title add an extra layer that is about healing?

CB. Well, I didn’t conceive of them as ex-votos because…it’s an artwork (both laugh).

JH. Right! I suppose I mean that they are so much like ‘real’ Etruscan votive heads, but then after reading other things you’d written, I wondered if the objects actually had another significance that might be quite different?

CB. Well it is really about the connection between archaeology and psychoanalysis – these two modernist constructions that began in the nineteenth century and such a huge influence on our lives now. Within Freudian psychology, the archaeology metaphor is a known thing that people have written a lot about. And of course, it makes sense, because you are taking away these layers and layers of things to uncover certain truths, towards some greater knowledge. So in terms of the archaeological dig, if you are encountering all these memories and histories that are in the shards, and you are scraping away the layers, there’s hopefully some kind of healing going on. Which is ultimately what psychoanalysis is all about. So that is the connection with the ex-voto – that I want to be made better by finding out this kind of stuff.

JH. Well thank you so much for showing us some of your past work, and for talking us through the complex relationship you have with classical antiquity. It’s fascinating to see how all these themes are intertwined in your work – archaeology, psychoanalysis, myth and metamorphosis - and how you have responded to all these different narrative and visual elements of ancient culture.

CB. You’re welcome!

Find out more...

Christie Brown's website contains more details of her work, and news of forthcoming exhibitions.