You are here

- Home

- Isobel Williams

Isobel Williams

Isobel Williams has written and illustrated The Supreme Court: A Guide for Bears (2017) and Catullus: Shibari Carmina (Carcanet, 2021). She has a chapter in Design in Legal Education (Routledge, 2022). Her translation of the whole of Catullus will be published in 2023.

This conversation with Henry Stead took place (in writing) between May and June 2022.

A PDF file of this conversation is available for download.

Henry Stead: Isobel, thank you for agreeing to this interview. I have so enjoyed spending time with your Catullus over the past few months. It is a collection that rewards close attention, so thank you for your patience. Can I begin by asking you about your early experiences with Latin poetry and the classical world more generally?

Isobel Williams: Thank you, Henry! It was drummed into me at a very early age that my big sister had read the Penguin Classics Iliad and Odyssey by the time she was seven. That put me off but I rallied thanks to second-hand books, a jumble sale habit and library tickets.

From bound volumes of The Strand Magazine I absorbed late Victorian images of classicism. We didn’t go abroad but my mother, who was from Wiltshire, had a Hardy-esque veneration for the numinous Old Sarum (the Romans came and went) where I picked harebells in the days before you had to buy tickets. The Workers’ Educational Association (my father was branch treasurer) provided slide lectures and gallery talks.

I saw Offenbach’s operetta La Belle Hélène (Helen of Troy in the French Second Empire) performed by Walton and Weybridge Amateur Operatic Society. I remain devoted to Carry On Cleo (1964).

I didn’t encounter poetry in Latin until grammar school.

HS: Your experience of Latin in the classroom at Woking Girls’ Grammar School comes across in your version of poem 34 especially. I wonder if you could tell us a bit about your experience of classics there, as it seems to have made quite an impression. And then what has been your relationship to Latin since school?

IW: In a febrile girls’ school atmosphere, 34 recollects the exam paper (‘turn over’), unseen translation and sick bay. I took O- and A-Level Latin thanks to inspired, dedicated teachers and I regret being a moody ingrate. I don’t recall all our set texts (studied in chunks, not complete) but in addition to sanitised Catullus I enjoyed Livy, the Aeneid and Julius Caesar’s efficient clarity in De Bello Gallico. Ovid’s Tristia rang a bell with this adolescent: me miserum, quanti montes volvuntur aquarum! [1] I have unfinished business with Horace’s town and country mice. We tackled Pro Caelio, so I was exposed to Cicero’s enduring hatchet job on Lesbia.

My surviving classics teacher, Jill Ferguson, is a supporter of the book, and a schoolfriend observed correctly that her opinion about it matters to me more than anyone else’s.

It saddens me that fights break out on #ClassicsTwitter over the issue of pupils learning things by heart. At school age, it’s a doddle. I use today what I memorised then. I say in the book that I shook off my schoolgirl self ‘trained to show the examiner that she knew what each word meant.’ This is not negative criticism of school or syllabus. If I’d got off my lazy arse and presented my teachers with a sideline of free translations, I would have been encouraged. At university I chose a Latin poetry option as a very small part of my English degree, then adult life ended formal study.

HS: About translation style: you say that these poems are ‘not (for the most part) literal translations, but take an elliptical orbit around the Latin, brushing against it or defying its gravitational pull’. This strikes me as very interesting way of translating. Most people would imagine that translation was about either achieving or, better, forging some kind of equivalence, between two languages and cultures. This practice would result in your new poem being a representation of the old poem. But this feeling of a ‘gravitational pull’ to be defied speaks of a commitment to the production of difference. Could you tell us more about this approach? Is this translation an act of rebellion?

IW: I aim to bring over the character of each poem with integrity, even if instinct says word-for-word won’t always work. But I am not a reliable witness to what I am doing. That was proved the last time I had my wallet stolen on a bus. And if I try to analyse my approach I fear it will bolt.

Sometimes I criss-cross the text, for example in 8, where I go off on what lawyers call a frolic of my own, but come back when soles (‘sun’, ‘the light of the sun’) emerges as ‘Japan’, the land of the rising sun [cries into drink]. I faithfully copied the metre of that one, the scazon.

What I don’t do is plonk Catullus down in a single new identifiable time or place, because to me he is floating between his time (you could go back further, to his sources Callimachus or Sappho) and our own, with all the cultural accretions he might have picked up on the way capable of operating simultaneously.

And is it always Catullus on the slab? Translation can be autobiography, just as drawing is: ‘I see the subject. Now, please step out of my light and let me intervene between it and you…’

I dream of being a spaced-out sibyl sitting over a geological fault line from which narcotic gases emerge, intoning what comes into her head. I want to achieve freedom and spontaneity but first I must use the whole arsenal to pin down sound, metre, meaning, nuance (as far as it is known today) and context (ditto). Then, while I’m deciding what to chuck out of the window, something wanders in through the cat flap. There are changes of heart and mind. Peter Green suggests in his notes that Lesbia’s sparrow is a blue rock thrush but he sticks to sparrow in his translation.

HS: Your introduction gives a thorough portrait of the ancient poet and his afterlife. What made you want to do this kind of scholarly work? And why pass it on to the reader?

IW: The publisher Michael Schmidt, with his vast experience of readers, asked me to add more about Catullus to a scrap I’d presented, so I was happy to write a digestible piece about his little-known life.

HS: Are there any versions of Catullus that you’ve come across since publishing that you would add now to this timeline of Catullan reception?

IW: Thank you for bringing Jack Lindsay to my attention. I admire his enthusiastic rhyming but he proves inadvertently that the order of Catullus’s poems shouldn’t be changed. Lindsay redistributed them to suit his notion of how loves and lives are organised. Friction and drama are lost, but it’s useful to have that demonstrated.

HS: We can tell from the acknowledgements that you enjoy working with others. Can we begin with your experience of attending the textual criticism class at Oxford? Why did you want to audit that class, and what mark has it made on your translation? As a reader, at times you feel a real fascination with the physical manuscripts of Catullus, their lacunae and idiosyncrasies.

IW: I don’t know why I was allowed to attend the class (once a week for two terms) which was given by Stephen Harrison and Stephen Heyworth, with Tristan Franklinos poised to step up. When I was invited to draw in a certain club, the management said: ‘She sits there like a little mouse and gets us.’ I took the same approach to the class. I am no textual critic and was not there to find a definitive text – no such animal – but it helped me enormously with my own brooding about Catullus. And I’ve got the wonderful class handouts. I use Mynors’s edition as the main source but occasionally my translation reflects more than one version of events, e.g. 56.

Textual criticism has the objective-versus-subjective struggle of art restoration, the same disagreements and mysteries across centuries. Nowadays every change you make, in either discipline, has to be reversible. Not so for the original scribes handling Catullus.

HS: Your collaborations and drawing in shibari (Japanese rope bondage) clubs must have been affected by the lockdowns of the Covid 19 pandemic. This contemporary context makes its presence felt in interesting ways in your translation. How did it affect the translation process? Can you give an example of how it became generative in your relationship with Catullus?

IW: I wrote most of the book before the pandemic. Later I added 46, reflecting tedious confinement, and called 109 Lockdown, but if anything outside those two poems suggests the pandemic it’s probably a bondage reference. Lockdown was the world’s biggest group bondage performance. As for Covid-era living, it has made me translate the rest of Catullus and even the epigrams of Callimachus.

HS: You translate 51 twice. Can you tell us a bit about this decision?

IW: 51 is a monster, a monolith. Perhaps being an embellished version of Sappho contributes to that. I attempted it more than twice (a cry for help, like my multiple attempts at 85) but these made my cut, a shibari and a non-shibari version. (And see @illalesbia on Twitter who translates it a lot.)

HS: Your poems regularly engage with other texts, e.g. Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream comes up quite a bit. What is happening here, is it conscious? How does this relate to your presentation of STRANDS? They appear to show your creative (and playful) technique of reading literal bondage into its figurative expression across all sorts of expression across the ages, literary and otherwise.

IW: I’m happy to take what comes and the Dream popped into my head as it is redolent of bondage performance (domination, transformation, flying). However, the play is a manual of how not to do it: a) stealth drugs (off-your-face shibari kills), b) lack of consent, and c) the unethical handling of Demetrius, who is left in suspension.

I loved compiling the STRANDS section, a mini-anthology of bondage metaphors from Plato to the Financial Times which shows the wide prevalence of this image.

HS: Your drawings are a big part of the experience of the collection, but these are not illustrations, are they? Can you tell us about the relationship between poem and image? Is it consistent?

IW: The drawings are from performances and workshops in London, Paris and Oxford. Each pairing of picture and drawing is a close marriage. I match the emotion in the poem with the emotion in the room when I was doing that drawing. My bondage blog http://boulevardisme.blogspot.com/ is paused for the pandemic.

HS: About bondage, sadomasochism and shibari: Now, I’ve taken a while to get here because as I was reading the collection, I learned quickly that although this is presented as the innovative hook for the translation, it sits within a far broader nexus of contemporary social contexts. It may be dominant, but it is not centrally operative in around half the poems. You say: ‘I use shibari simply as context’. Can you expand on this? What exactly do you mean by that? And did the framework of bondage ever feel restrictive to you while you were preparing the translation?

IW: Someone I met at life class suggested I might like to draw shibari, then explained what it was. For me it turned out to be a surprisingly fast-moving subject to draw – with detachment, which helps with observation. I also went the fetish club Torture Garden (no drawing allowed) a few times to see what people were wearing. (Shibari is a subset of fetish.) People who think it is daring or transgressive to go to such places should get out more, preferably to Kensington Gardeners’ Club which has the same congenial, unruffled special-interest vibe, with tea.

The shibari world gave me a locus for this ancient Roman switch, who is a howling submissive with Lesbia and a bitchy dominant with the boys. I also feel he would appreciate the technicalities of this martial-art-derived discipline. The context, which supplied metaphor and idiom, could be used or ignored as appropriate to each poem. I could stop worrying and focus on the writing.

HS: Poems 7 and 99 seem important to get a handle on the shibari context. In 7 there is a joyful humour in the application of the new context, for example cum tacet nox becomes ‘when the night is ball-gagged’. But there is a seriousness too, for example, in the use of the Japanese words for different styles of bondage. 99 sees Juventius exacting his revenge on Catullus, for ‘helping himself’ (to a kiss?), literally suspended in an ‘inverted crucifix’ and then ‘spatchcocked’. While 7 (and, e.g. 86) seems to evoke an elevated artistic form, 99 (and e.g. 6, 45, 63, 76-81) conjures a hazy demimonde of German sex clubs in Vauxhall. Does this represent the diversity of the shibari scene?

IW: Shibari performance clubs, which promote a nerdy devotion to knots, are not sex clubs, nor can drink or drugs be in the mix when practitioners must always know where their safety shears are. The book does however suggest a wider context for Catullus’s late Roman Republic circle, ranging (unlike me) from sweaty dives to swanky private orgies.

I’m glad you find seriousness in the Japanese of 7, in a passage where Catullus himself is obscure. With regard to 99, it pays to remember that he could have walked away from the conflicts he describes (assuming they exist). But maybe conflict powers his creativity. And he is transactional. He dwells on what people owe him emotionally and financially. He is aware of boundaries, even if he decides to subvert them. If he were your guest at a fusty private members’ club he'd behave impeccably, perhaps making a discreet arrangement with a young waiter later. Ovid would turn up in the wrong shoes, make calls in the no-phone area and leave early to shag a friend’s wife.

‘Elevated artistic form’: the shibari crowd will be cheering – their commitment to technique and artistic impression recalls Olympic figure skating.

HS: Ipsitilla writes back! I love this poem. Could you tell us a bit about how it came about?

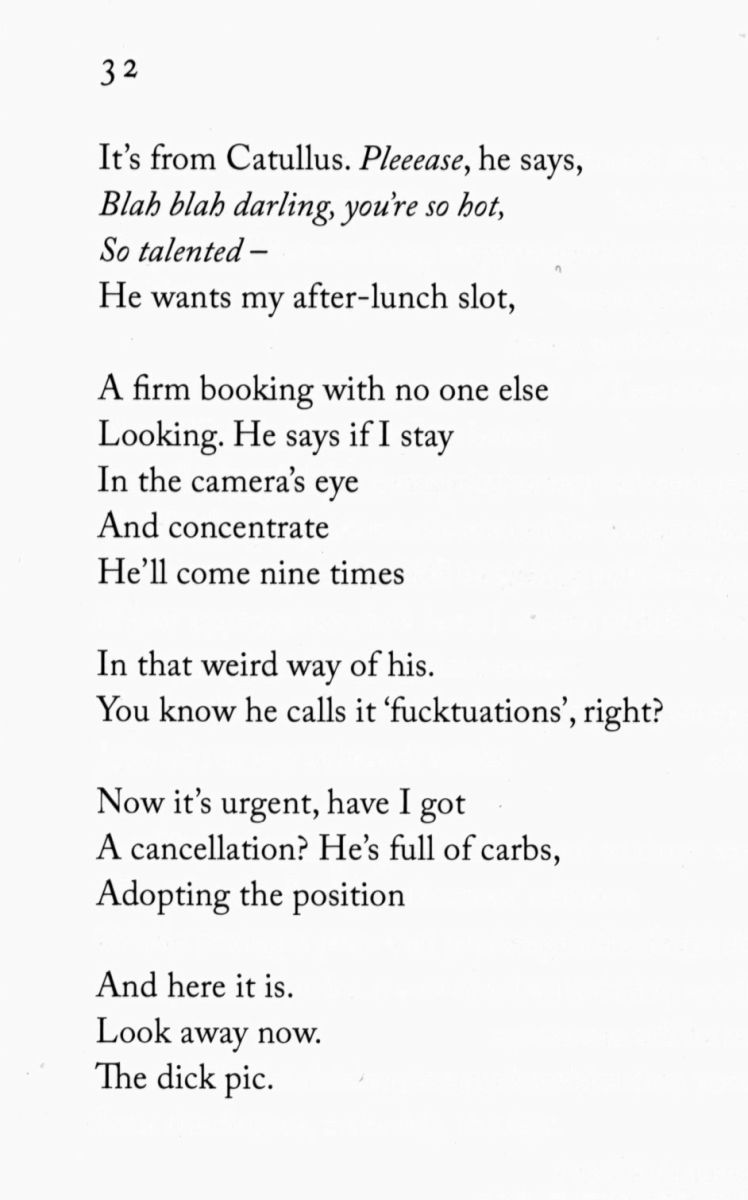

IW: At first 32 seems a mess of cognitive dissonance. His coy coinage fututiones – ‘fucktuations’ – is revolting. And does his silly warning to prepare for nine successive bouts cut any ice with a busy professional? I voice it as an exasperated woman, not a wheedling prick.

On the other hand… Catullus, who knows all about comic timing, probably read out his works as after-dinner entertainment and the ‘nine times’ line would get a laugh – self-disparagement can’t be ruled out from this poem about something unachieved.

This reminds me of Ad Pyrrham (1959) edited by Ronald Storrs, a fascinating multilingual anthology of overwhelmingly male translations of Horace's Book l, Ode 5. Two of the very few women, Aphra Behn and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, switch the ode from the male to the female perspective. I’d like to buy a copy if anybody has one.

HS: Now, I’d like to circle back to your approach to translation. In your introduction you liken translation to shibari, saying that the process creates an impression like ‘rope marks on the skin’. Here is the full quote. You say: ‘Translators must try to avoid giving a text the head of a donkey through misreading or doubtful taste, but at least they do no permanent harm to the original. Rope marks on the skin should leave a pleasing pattern but will soon fade.’ What does this metaphor tells us about your relationship to Catullus and your approach to translation?

IW: The marks on the skin when the ropes are removed ruthlessly expose the rigger’s skill, or lack of it, and should be orderly, not awry. In context, the ass’s head is Bottom’s and I’m punning with the rope bottom, the person tied. Translators do no permanent harm to a source – unless they put someone off it for life, of course.

I believe Catullus thought he was writing for posterity. Our relationship? He’s on my marble slab with a few bits missing – perhaps they’ll turn up at the back of the freezer. I approach translation with respect, humility, sharp tools and a bucket.

HS: You also tell us: ‘Shibari is a form of translation. The top arranges the bottom in a shape he or she could not hold or maybe even attain alone.’ If we read ‘translation’ back from this: the role of the translator is perhaps surprisingly active and creative. How would you explain this?

IW: I don’t believe in synonym, let alone translation. Small boy ≠ little boy. Change takes place; the translator decides what kind. An old friend barked the following at me:

- ‘What right have you got to translate Catullus?’

- ‘Translation isn’t writing!’

I am going to duck both those. Some people think translation is what happened before they gave up on French at school and that there is one right answer. The anthology Ad Pyrrham (above) is a lovely reminder that translations are as individual as our fingerprints.

HS: Who is the perfect cross-over shibari/Catullus figure?

IW: I asked La Quarta Corda – Florentine bondage rigger, violinist and more – to film himself reading any Catullus poem. He produced the most mesmerising reading of Latin (Poem 36) I’ve ever seen.

For those interested, other readings and performances from the book are here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VMnC1SGTzU&t=743s

Thank you very much for such a close reading, Henry. Had this been a spoken interview there would have been a lot of ‘er um dunno’ from me. It’s been great to have the virtual company.

----

[1] Loeb translation Wretched me! what vast mountains of water heave themselves aloft!