You are here

- Home

- Football in Burundi is a tool for reconciliation and political legitimacy

Football in Burundi is a tool for reconciliation and political legitimacy

29 September 2020

Celestin Mvutsebanka addresses key entanglements between politics and football in Burundi. His analysis outlines how football gradually evolved from a tool for social cohesion within and between military, public and civil spheres into a tool for political legitimacy, deployed by political actors for their own propaganda. Célestin Mvutsebanka is a PhD student at the Doctoral School of the University of Burundi. He is attached to the University Research Laboratory in Physical and Sport Activities for Social Development and Health (LURADS). He is writing a thesis entitled ‘Burundian football: an instrument for strengthening collective identity and means of reconciliation between ethnic groups.’

This blog forms part of the Idjwi Series which results from a writing retreat on Idwji Island in Lake Kivu, DRC during which regional researchers gathered to present and refine their research.

In Burundi, football has become an important instrument for reconciliation, social cohesion and the consolidation of political legitimacy. Public institutions started to mobilise football to facilitate the implementation of institutional reforms induced by the peace process, such as demobilisation and the re-integration of ex-combatants, and to improve relations between political, civil and military spheres. Building on Désiré Manirakiza’s work on the sociology of football, I investigate how former combatants of the ruling political party, the National Council for the Defence of Democracy – Forces for the Defence of Democracy (CNDD-FDD), have become fervent supporters of football and continue to exploit it to legitimise their own power.

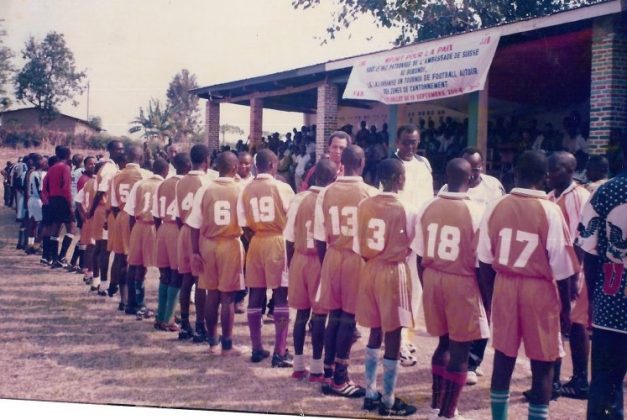

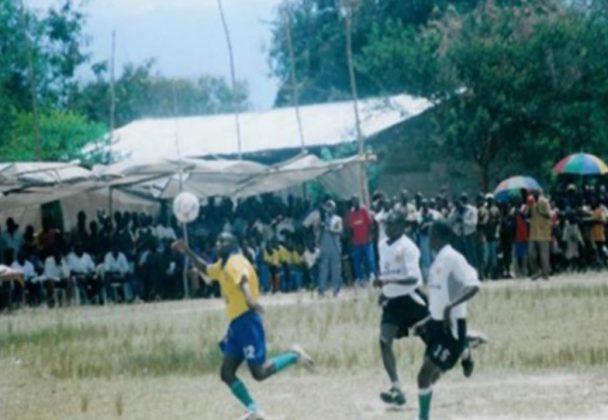

From 1993 to 2008, Burundi experienced a civil war fought between former Burundian Armed Forces (ex-FAB), then dominated by Tutsi, and the mostly Hutu armed political parties and movements. Following a ceasefire agreement signed between Burundian institutions and the then-armed CNDD-FDD political movement in 2003, CNDD-FDD combatants joined cantonment camps to integrate the official army or be demobilised. As early as December 2003, football tournaments were organised to facilitate engagement between the different components of the newly formed army, namely the ex-FAB and CNDD-FDD ex-combatants, transforming football into an instrument for reconciliation and social cohesion.

These sporting experiences were perceived as successful and extended across the country, with reconciliation efforts through football encouraged between returning refugees and residents in various villages. Since 2005, however, this process has been gradually taken over by CNDD-FDD elites.

As soon as he came to power in 2005, former President Pierre Nkurunziza, a fervent football enthusiast (recently deceased as of June 2020), continuously promoted through various initiatives the usefulness of football. He created an amateur football team (‘Halleluyah FC’), and a year later established a football academy (‘Le Messager FC’). Through his club, he organised a football championship to foster reconciliation and socialisation between members of the government and the civilian population. The competitions organised by Nkurunziza helped to consolidate his power by bringing political elites closer to the population. Similarly, an interdepartmental football championship was re-introduced and refined in 2006.

As soon as he came to power in 2005, former President Pierre Nkurunziza, a fervent football enthusiast (recently deceased as of June 2020), continuously promoted through various initiatives the usefulness of football. He created an amateur football team (‘Halleluyah FC’), and a year later established a football academy (‘Le Messager FC’). Through his club, he organised a football championship to foster reconciliation and socialisation between members of the government and the civilian population. The competitions organised by Nkurunziza helped to consolidate his power by bringing political elites closer to the population. Similarly, an interdepartmental football championship was re-introduced and refined in 2006.

Image (left) shows a match of reconciliation between former Burundian Armed Forces (ex-FAB) and former combatants of the CNDD-FDD in December 2003, in a cantonment camp located in Bubanza (western Burundi). Source: National Olympic Committee of Burundi.

In the same vein as former President Nkurunziza, Révérien Ndikuriyo, former President of the Senate and President of the Burundian Football Federation (F.F.B), also organised several reconciliatory football matches. Among his initiatives are the creation of Black Eagle club (‘Aigle Noir’ – also the symbol of the ruling party) and the construction of a football stadium in the rural province of Makamba.

Image (right) shows a match of reconciliation between the Tutsi and the Hutu, in December 2003, in Bubanza. Source: National Olympic Committee of Burundi.

In most cases these games, aimed at reconciling and building social cohesion, often conclude with propaganda speeches. Such initiatives can be viewed as the ‘politics of presence’ or ‘legitimation by proximity’, where political elites make significant efforts to remain close to their electorates. Yet, since 2005, the two leaders of the CNDD-FDD party have been accused by their political opponents of instrumentalising football for electoral purposes.

Despite such accusations, Révérien Ndikuriyo has continued to establish football associations in all communes and provinces of the country as promised in his electoral campaign – his initiatives have helped mobilise Burundian youth, an important part of the voting population. Later, under the influence of Nkurunziza, Révérien launched the project ‘On every country’s hill, a football team’, and in a further instrumentalisation of the sport the two leaders introduced a senior football championship in 2006, in which teams compete for a cup in honour of the President. The cup is attended by a large audience and has become an opportunity for a demonstrative display of power by the regime, illustrating a gradual collusion between politics and football.

This political instrumentalisation of football by elite members of the state has been widely imitated. Several political figures of the CNDD-FDD started taking charge of their respective hometown football teams. For those political leaders, gathering local populations in shared spaces was about maximising their political successes. For instance, among many others, the current Ombudsman of the country Edouard Nduwimana, the former Second Vice-President of the Republic Joseph Butore, and former President of the National Assembly Pascal Nyabenda are all president of their hometowns football clubs. The sport’s politicisation across the country is motivated by its effective contribution to electoral rallies, assessing loyalty of a population to the regime and demonstrating the leadership and strength of the CNDD-FDD party.

Entanglements of football and politics are also seen in the organisation of games during Community Development Works (TDCs) that take place in Burundi every weekend. Désiré Manirakiza understands TDCs as an integral part of grassroots politics and the country’s ‘body politics’: they encompass practices in which political elites perform manual labour for the construction of public facilities – including but not limited to sport facilities – for political ends. My research additionally draws attention to how party-affiliated youths take advantage of TDCs and football matches to exercise a form of ‘social control’ by identifying those who do not participate in these activities, treating such people as opponents of the regime.

Burundi’s ‘reconciliatory football’ has always been as much about marking political scores as fostering social cohesion between communities and former combatants. That former CNDD-FDD combatants today have become fervent ambassadors for a sport with clear political incentives has no sign of changing.

Read more in the paper, ‘The Burundian football under the sway of the political authority: towards a systemization of its development and instrumentalization as a reconciliation strategy’ by Célestin Mvutsebanka, and ‘Quand le Football Burundais devient un Enjeu Identitaire et Politique’ by Célestin Mvutsebanka and Salvator Nahimana.

The Idwji Writing Retreat was jointly funded by The Open University’s Strategic Research Area in International Development and Inclusive Innovation and the Centre for Public Authority and International Development (CPAID), LSE.

Photo by Jannik Skorna on Unsplash.

Share this page:

Contact us

To find out more about our work, or to discuss a potential project, please contact:

International Development Research Office

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0)1908 858502

E: international-development-research@open.ac.uk

.jpg)