You are here

- Home

- blog_categories

- Inclusive Innovation and Development

- Spatial Models and Wicked Problems - Belinda Wu

Spatial Models and Wicked Problems - Belinda Wu

30 December 2016

A scientific model can be a conceptual, mathematical or physical representation of a real-world phenomenon, one that is often only partially understood and not easily observable.

This means that although models can never hope to replicate the whole of reality, they can provide an entry point to the study of complex problems, especially when these would be too costly (both financially and in human terms), too difficult or even impossible to experiment on in reality. As the British statistician George Box put it, 'All models are wrong, but some are useful.' Models then can – and frequently do – allow us to understand complex systems through their simpler representation.

Wicked Problems

This is why, when combined with quantitative analyses, they can be particularly helpful in facilitating the evidence-based decision-making involved in some long-standing social development issues, including those known as 'wicked problems'. These are social or cultural problems that – due to the incomplete or contradictory knowledge that surrounds them, the number of people and the economic burden they involve, and their interconnected nature – are particularly difficult to solve. Typical examples include poverty, sustainability, equality and wellbeing.

Although content remains the most important aspect of any piece of information, time and space provide vital context. Indeed, without them information remains incomplete and can be dangerously misleading. By providing them, spatial models and analyses (SMAs) thus offer the potential to tackle some of these long-standing problems.

That’s why they’re used so widely in development studies – from geopolitics, spatial economy and inequality through to demographics, infrastructure planning and the sustainability of local ecological systems. The more sophisticated representation of complex social systems they allow facilitates better planning and policy-making. In the Sahara, for example, we’ve seen how GPS- and GIS-enabled models helped tribal shepherds, while farmers in Brazil were better able to prepare for climate changes. Electricity, water and transport networks can be mapped out in order to specifically include disadvantaged populations in the Global South and the spatial distribution, density, flow and evolution patterns of populations and the world’s resources can be captured to promote sustainable development.

Geography Matters!

In short: geography matters! Ultimately, everyone lives in a local area and is affected by what’s going on around them. SMAs reveal not only the usual statistical features but spatial patterns and relationships, too, which can then be visualised in a range of maps. This makes them a particularly powerful tool with which to engage both the general public and policymakers – they can do so more directly and much faster than other models. After all, not everyone understands an equation or a chart, but most people can read a map.

In addition – and of particular importance when it comes to tackling wicked problems – the geographical dimension of SMAs facilitates inclusive innovations through three main features. First, geography can offer a useful surrogate for a complex mix of factors causing an issue – a persistently low birth rate in a certain area, for instance. While we may not be sure which factors we should include in a single model to study this – it could be the outcome of a series of complex interactions between a set of political, economic, demographic, cultural and environmental factors – we can simply apply the spatial difference (by applying a lower birth probability to the female population of childbearing age) to represent the unclear causes of an issue within a location.

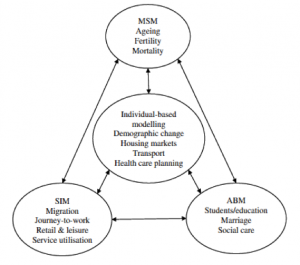

Second, geography can link data together to provide a fuller picture. Although comprehensive data are often not available in developing countries, as long as those collected through different channels share the same geography, SMAs can link them to help fill the knowledge gaps. Similarly, different paradigms – different modelling approaches – can also be linked. For example, I invented a hybrid-modelling framework (see figure 1 at top of page) that combines a micro-simulation model from economics, an agent-based model from artificial intelligence and spatial-interaction models from geography. The more sophisticated representation of complex social systems this offers facilitates vastly improved planning and policymaking.

Finally, geography provides the perfect vehicle for the delivery of developmental policies that best reflect local needs. In comparison with polices driven by macro-econometrics, the location-based policies that SMAs enable lead to improved targeting and more nuanced policies for inclusive innovations.

Fig 1: Wu, B M; Birkin, M H; and Rees, P H (2008), A spatial Micro-Simulation Model with Student Agents, Journal of Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 32, 440-453, DOI: 10.1016/j.compenvurbsys. 2008.09.013.

Dr Belinda Wu is a Research Fellow in Development Policy and Planning and a member of the SRA in International Development and Inclusive Innovation. Belinda is a Human Geographer who specialises in spatial decision-making support, and this post is a summary of the presentation from her recent workshop: What Good Can Models Do with the Wicked Problems.

Share this page:

Contact us

To find out more about our work, or to discuss a potential project, please contact:

International Development Research Office

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0)1908 858502

E: international-development-research@open.ac.uk

.jpg)