You are here

- Home

- The latest significant step in the UK’s development agenda

The latest significant step in the UK’s development agenda

22 June 2020

The merger of the UK’s Department for International Development into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office reflects a narrow nationalist agenda that stands opposed to the global upheaval against racism and the colonial past, argue Susan Newman and Sara Stevano.

Johnson’s announcement on 16 June that Department for International Development (DfID) would be merged into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) has been met with criticism and condemnation from aid charities, NGOs and humanitarian organisations. By institutionally tying aid to UK foreign policy objectives, the merger would shift humanitarian aid away from the immediate needs for relief and longer-term development.

This latest move to merge the departments should be seen as the latest, and a very significant, step in the restructuring and redefinition of British Official Development Assistance (ODA) to serve the interests of British capital investment abroad, that has been taking place over the last decade. These developments need to be considered within a wider shift in development policy that has been shaped by the demand for new assets by investors in the global North in the context of a global savings glut that has grown out of economic slowdown.

The last 30 years have seen dramatic transformations in the role of British aid in international development. DfID was formed in 1997, when it was separated from the FCO. Such disincorporation came with a partial redefinition of development away from the protection of capital’s interests enmeshed with the UK’s former colonial ties, and an embracing of the security agenda and the universalisation of development as moral imperatives. The UK played a significant role in shaping the global development agenda, with Clare Short, Secretary of DfID under New Labour, taking the lead in the promotion of the International Development Goals (IDGs), which paved the way to the development of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Amidst the economic and political turbulence of the global financial crisis and its austerity-shaped aftermath, there has been a recent shift in the strategic focus of the UK aid strategy. Growing importance is now again attached to promotion of the UK’s national interest. A key mechanism for achieving this, as set out in the 2015 aid strategy, has been to direct the aid budget away from DfID to other government departments and cross-government initiatives. Between 2014 and 2016, there was a 12 percentage point drop in the proportion of the ODA budget received by DfID, so that by 2016 more than a quarter of the aid budget (£3.5 billion) was being spent outside DfID, up from 14% two years earlier.

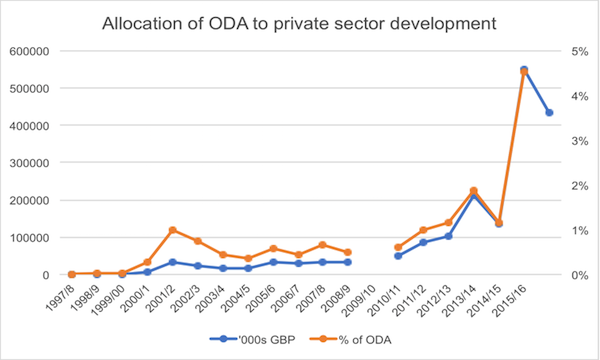

There is a long history of private sector involvement in British overseas development but there are qualitative changes linked to the restructuring of the British ODA apparatus. Striking changes can be observed in the allocation of ODA to private sector development, with dramatic increases from 2013/2014 onwards.

Source: Created by authors using data from DFID Annual Report 1997-2015/2016

Commercial interests and private sectors involvement have been part and parcel of British ODA since the outset with concessional lending tied to procurement of goods from the UK and the provision of export credit at favourable terms by private banks subsidised and guaranteed by government to win business from developing countries. For the majority of its history, ODA has been the remit of the Foreign Office. The Colonial Development Corporation (now named the Commonwealth Development Corporation, CDC) was formed in 1948 with the mission to ‘do good without losing money’ and ‘augmenting the productive capacity of the colonies to provide food and raw materials to meet the pressing needs of post-war Britain’. CDC was partially privatised in 1999 only to be brought back into government ownership, via its purchases of all private equity in CDC in 2012, to become the UK’s main development financial institution. Mawdsley refers to the CDC as the ‘centrepiece of existing mechanisms’ to encourage partnerships with business. For example, the CDC has taken an interest in the so-called gig economy in Africa owing to its potential to generate returns for investors with limited investment sufficient to offer some ‘perks’ to workers, such as training and links multinational companies, that cannot be obtained via employment in the informal economy.

Johnson described the DfID budget as a ‘great cashpoint in a sky’. DfID’s budget had indeed bucked the trend during a decade of austerity. Not only were no cuts made to the department, an injection of finance was made to bring CDC back into full government ownership under the Commonwealth Development Act of 2017. Over the last 10 years, DfID has undergone considerable internal restructuring in relation to its strategy to support private investment in the Global South through vehicles such as public–private partnerships and development impact bonds. An expansion in the expenditure of its Corporate Performance Group from 0.05% of the DfID budget in 2008/9 to 3.2% by 2015/16, and its commitment to Payment by Results as part of aid strategy in 2015, reflect a shifting role for DfID towards the monitoring and evaluation of private businesses on behalf of UK investors.

The merger of DfID into the FCO is thus the latest in an ongoing reorientation of British ODA. It is nonetheless significant because it marks a more defined break away from aid as humanitarianism. The re-incorporation of DfID into the FCO reduces the possibility to align British aid with the interests and development plans of recipient countries, thus giving rise to a ‘new-model colonial policy’, as recently argued by Oqubay. It places ODA firmly within a narrow nationalist agenda with deep resonances with empire that stands opposed to the raging Black Lives Matter movement and the calls for reckoning with the imperialist history of the UK. This is all the more significant in the current historical moment, when the anti-racist movements have been reignited in the UK as the Covid-19 pandemic is making visible how institutionalised racism can make the difference between life and death, with BAME people disproportionately affected by coronavirus owing to their economic deprivation, social marginalisation and over-representation among low-paid ‘essential’ workers.

This merger drastically completes a longer-term process of restructuring of British ODA by annihilating the possibility for aid to be used primarily for humanitarian relief based on immediate needs or to deal with longer term issues of poverty reduction and economic transformation through industrial policy. As unwelcome as this merger may have been at any time, its announcement amidst a pandemic that is ripping through the Global South, the global economy set for a protracted downturn, the global upheaval against racism and the colonial past in opposition to right-wing nationalist populism make it particularly damaging and politically charged.

Professor Susan Newman is Head of Discipline for Economics at The Open University. Dr Sara Stevano is Lecturer in Economics in the School of Oriental and African Studies.

Image: Michael Haig/Department for International Development

Share this page:

Contact us

To find out more about our work, or to discuss a potential project, please contact:

International Development Research Office

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0)1908 858502

E: international-development-research@open.ac.uk

.jpg)