You are here

- Home

- Radical Thinking Key to Achieving SDGs

Radical Thinking Key to Achieving SDGs

26 April 2019

Today's blog is written by Matt Foster, Director of the International Development Office at The Open University.

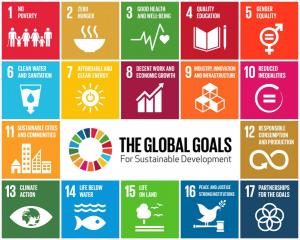

One aspect of the UK parliament’s work that has disappointingly not been making the headlines is its role in reviewing the UK’s progress towards achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This is now under way with a parliamentary enquiry in place and consultations across the country which will help to produce a voluntary national review (VNR) which will be submitted to the UN alongside VNRs from 50 other countries in July of this year. The UN’s High-level Political Forum will then use these to conduct a thematic review focused on six of the SDGs in an attempt to stimulate greater urgency and more considered action. With just over 10 years left to achieve Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (to give the SDGs their full title), we are expected to be way off track.

With the full UK review report due to be submitted by 14 June, the DSA provides an opportunity to take an early look at what’s inside and I hope that it’s one you’ll seize by joining us at our session on 19 June. During it, a panel discussion will share some initial insights into the review and – as I think it’s fair to say that the jury is still out on how seriously the UK is taking the SDGs across all sectors – we may get some indication of an answer to this. (We should also discover if the review passes the “review of the reviews test”).

It all seems a very long time since the UK government was playing such a prominent role in the formation of Agenda 2030. Indeed, 2015 – when David Cameron lobbied unsuccessfully to reduce the number of goals to a maximum of 10, as otherwise “there’s a real danger they will end up sitting on a bookshelf, gathering dust” – now feels like a golden age. Sadly, it also looks as if he was right as in 2016 the UK government stated there was no need to develop any form of implementation plan on the basis that each Ministry had embedded the SDGs in its own plans. Although later, in March 2017, the government did produce a document describing their approach to delivering the goals both domestically and internationally (Agenda 2030: Delivering the Global Goals), it’s hard to see how this could be used as a basis for a review. In fact, rather it resembles a “Brand GB” sales brochure with a few headlines in very large font about the UK’s achievements and expertise under the headings of each goal.

As someone who has worked in and around UK NGOs for many years, I’m also certain that most of these are still struggling to embrace the SDGs. Other than an impressive knowledge of the 17 goals and their 169 targets, and a shared view that “if we can get more resources, we’ll be able to deliver them”, I’ve not seen any fundamental changes to their ways of working. And, if we turn to universities, an index developed by the Times Higher Education to rank universities’ direct impact in society (using the SDGs as a framework), placed only 17 UK universities in the top 100 (out of a total of 500). Of these, the University of Manchester led the way in joint third place with the University of British Colombia. (The University of Auckland came first, with McMaster University in Ontario second.)

Although the methodology used needs considerably more scrutiny if we’re to understand what these findings really mean, I’m not sure they actually highlight anything that significant. However, a consensus does seem to be re-emerging on the need to think less about the narrow focus of each goal and target and more about the fundamentals of how to enable real change. The World in 2050 Initiative (TWI2050), for example, highlighted six exemplary transformations which offer a good starting point for working out what transformative change might really mean, while last year the World Economic Forum highlighted three ways to accelerate SDG progress which drew attention to the shifts that would be required in ways of working.

I for one certainly hope that DSA 2019 will mark a shift in our own thinking and provide a genuine catalyst for greater collaboration between universities and NGOs. While I’m pleased to report that there are already some great examples of this, there is scope to do so much more and, in particular, for universities to play a far greater role in society’s big conversations and in leading action beyond teaching and research.

With the OU’s track record of radical thinking and action (exactly 50 years ago this year, it was the first to open up higher education to the masses) I hope that as hosts of this year’s DSA Conference, we can inspire similar radical thinking and action for international development in 2019.

Tickets for #DSA2019 are now available.

Share this page:

Contact us

To find out more about our work, or to discuss a potential project, please contact:

International Development Research Office

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0)1908 858502

E: international-development-research@open.ac.uk

.jpg)