You are here

- Home

- blog_categories

- Inclusive Innovation and Development

- Studying teachers' use of language in Indian low-cost English medium schools

Studying teachers' use of language in Indian low-cost English medium schools

18 December 2017

By Dr Lina Adinolfi

The teacher calls out: ‘Mobile phone is a very important means of communication. It is a very important…?’ ‘Means of communication!’ the class chants back. ‘You can buy postcards. You can buy …?’ prompts the teacher. ‘Postcards!’ the children respond in unison. Every so often the teacher asks: ‘Understand?’ and the students reply: ‘Yes, Sir!’

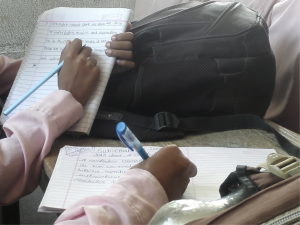

I am in a Social Science lesson in a school in northern India, where 35 children aged 11 are seated shoulder to shoulder in closely fitted rows, their textbooks and note books balanced on top of their school bag on the cramped desk space in front of them.

This is one of India’s growing numbers of low-cost English medium (LCEM) private primary schools. Demand for these schools – the majority of which are unregulated – has been driven largely by parental dissatisfaction with the quality of provision in the government system. The recent emergence of this sector is testimony to the sacrifices that poor families will make to secure what they believe to be a better education for their children.

The use of English as the medium of instruction (EMI) in such schools nevertheless runs counter to the national language-in-education policy which recommends that the state language (often but not always corresponding to the children’s mother tongue) be used as the main medium of teaching and learning, with an additional Indian language and English being taught as curricular subjects.

With its population of 1.2 billion accommodating multiple religious, linguistic and economic groupings across its 35 states and union territories, India is one of the most diverse nations in the world. Of its 450 or more recognised languages, which employ 25 unique writing systems, English maintains an elite status and, as a legacy of the colonial period, continues to be the medium of instruction in higher education.

In visiting a sample of LCEM schools in a relatively deprived Hindi-speaking state in northern India, the intention was to learn more about their teaching practices. A Hindi-medium government primary school in the same area was also visited for the purpose of comparison.

Didactic approach is common practice

Independent of the subject taught, a common feature of the nine lessons observed in the LCEM private schools visited was the traditional, strongly didactic transmission approach employed. This regularly involved the teacher reading lengthy passages out loud from the English textbooks, paraphrasing each sentence into Hindi as they did so, while the students followed the same text in their own books.

While the LCEM school teachers had a degree in the subject they taught, they had undergone no formal pedagogic training and reported having received no induction or guidance on classroom language use. Yet the practice of moving between English and Hindi in order to facilitate student understanding appeared to be both intuitive and legitimate. Given that EMI is often construed to mean ‘English only’, the extent of teacher codeswitching in this context was thus somewhat unexpected. Similar movements between languages were observed by the teachers of the two English language lessons observed in the Hindi-medium government primary school visited.

Of interest, however, was the observation that, although much of such codeswitching involved the translation and paraphrasing of words and phrases, little distinction seemed to be made between what the students might already understand and what they might not. More significantly, there were no instances of teachers drawing the students’ attention to any aspect of the English language encountered – no contrasting of one word with another of similar meaning, no explanation of its form, no focusing on a specific sentence construction.

Moreover, such codeswitching was only on the part of the teachers. In general, the students spoke very little. One of few exceptions was in the LCEM school Social Science lesson referred to above, whose teacher regularly repeated sentences from the English textbook, using rising intonation as a prompt for the students to supply the missing word or phrase in the second of such pairs of utterances. The children responded in masse, often shouting out the answer loudly.

Students are mainly silent

However, in most of the lessons visited in both types of school, the students were not encouraged or invited to speak in any language. In one English language lesson, the students were offered no opportunity to speak at all. A single child’s reading aloud of a short passage from the English textbook corresponded to almost all of the student talk that occurred in three of the classes observed.

Whole class English responses to highly constrained teacher questions or prompts corresponded to the most common forms of student talk, as in the example above. In nine of the 11 observed lessons, the students had no or limited opportunities to respond to the teacher individually and in the other two lessons, only very few students did so.

With the exception of one lesson in which a small number of students talked in pairs as they worked through the textbook activities, such collaborative peer talk was not encouraged. One or two students also responded to the teacher’s invitation to ask her questions in that class. However, no child requested clarification in any of the other lessons observed.

The limited forms of student talk made it difficult to gauge the children’s levels of comprehension and proficiency in English, as a class or individually. Classroom learning thus primarily involved listening to the teacher, completing short comprehension questions in the textbook, and copying from the board, with revision for written tests for homework.

Teacher-dominated pedagogy

Although teacher talk far outweighed student talk overall, in some cases the teachers themselves spoke very little. In one lesson, most of the class time involved the teacher silently writing on the board while the students copied the lists of words into their notebooks. The majority of teachers had very limited competence in English and were heavily reliant on the language of the textbook.

While valuable, the bilingual instructional practice of codeswitching to support learning was thus combined with a highly didactic transmission teaching style in which students were largely silent. A reflection of cultural mores and the teachers’ own experiences of schooling, Indian attitudes towards effective educational practices are difficult to shift, as evidenced in government teachers talking enthusiastically about the new forms of student-centred learning that they have learnt about in their training, while struggling to enact them in their classrooms.

India’s crisis in learning

A number of factors are thought to contribute to the widespread problem of student underachievement across the Indian education system as a whole. The majority of Indian children who complete primary school do so without having attained the intended levels of home language literacy, core subject knowledge, or English language ability. This greatly restricts their prospects for continuing into secondary and higher education.

According to the most recent Annual Status of Education Report (2016), the proportion of children in the third year of primary school (Class 3) who are able to read a text of at least first-year level is 42.5%, with 73.1% of students being able to read at this level by Class 8. Similarly, the level of arithmetic, as measured by children's ability to do a 2-digit subtraction in Class 3 is 27.7%, while for their ability to do simple division problems in Class 5, it is 26%.

Although India has been committed to universal primary education since 2009 and enrolment is currently over 96%, only 51.4% of the country’s population complete primary education, with the percentage dropping to 37.5% for the completion of lower secondary and 26.8% for upper secondary.

Different atmospheres in the two types of school

This study revealed that the teachers used a similar bilingual instructional approach in both the LCEM schools and English lessons of the government schools visited. A notable difference, however, was the atmosphere in each type of school. The LCEM private schools were distinguished by their high levels of discipline and rigorous student testing regimes, in a bid, presumably, to contribute to results that would satisfy the fee paying parents to whom they were accountable. Their overcrowded classrooms, in turn, reflected their focus on profitability.

In contrast, the government school, which catered for some the poorest children in the area, consciously adopted a nationally promoted ‘loving’ approach, encouraged outdoor play, and acknowledged the considerable challenges facing the first generation learners in their care.

The country’s government school system is currently undergoing an extensive programme of investment and improvement. Of value would be for the public and private education sectors to work together in jointly reviewing their practices, with the aim of placing effective learning at the heart of classroom teaching in India.

Dr Lina Adinolfi is a Lecturer with expertise in language in education within the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics at The Open University, UK. She was the Academic Lead for this study’s fieldwork in India, with the support of Snehal Shah. A copy of the EMI research report can be found here.

This is the fourth in a series of six blogs by the EMI research team. To read more in the series:

Great opportunities to support EMI with multilingual practices by Dr Elizabeth J. Erling, formerly Senior Lecturer in English Language Teaching and International Teacher Education at The Open University, is now Professor of ELT Research and Methodology at the University of Graz.

Ghana’s teachers need permission and support to incorporate local languages into EMI teaching by Kimberly Safford is a Senior Lecturer in Primary Education Studies and International Teacher Development at The Open University.

Photo by Dr Lina Adinolfi. Photo is not to be used without seeking permission from Dr Adinolfi.

Share this page:

Contact us

To find out more about our work, or to discuss a potential project, please contact:

International Development Research Office

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0)1908 858502

E: international-development-research@open.ac.uk

.jpg)