Chatterton, April 1826: Britain’s Hidden Massacre

The Morning of the Massacre

The Chatterton Massacre took place on the morning of the 26th of April 1826 outside Aitkens and Lords Mill, in the village of Chatterton, near Ramsbottom, east Lancashire. At least six people were shot dead by British soldiers. The massacre occurred on the third day of the weavers uprising, which had started on the 24th of April 1826 at Whinney Hill, Accrington and had spread through Oswaldtwistle, Blackburn, Darwen, Helmshore and Haslingden over its first two days. On the third day an enormous crowd, estimated of between 3,000 to 4,000 people, made their way from the adjacent towns of Haslingden and Rawtenstall along the sides of the south Pennine moors to Dearden Clough Mill in Edenfield and then down the steep hill towards the mill at Chatterton. When they arrived at Chatterton Old Lane, the local magistrate and the soldiers were waiting for them.

Not long before 11.00am, the local magistrate, William Grant, read a short extract from the 1714 Riot Act. The reading of the Riot Act was significant for two reasons: first, it meant that soldiers could kill people in the crowd and there would be no resulting criminal prosecutions and second, its reading was hugely significant for the mill owners because it meant that through the Lancaster Assize Courts, they could claim back full compensation for any damage done to their property by the crowd.

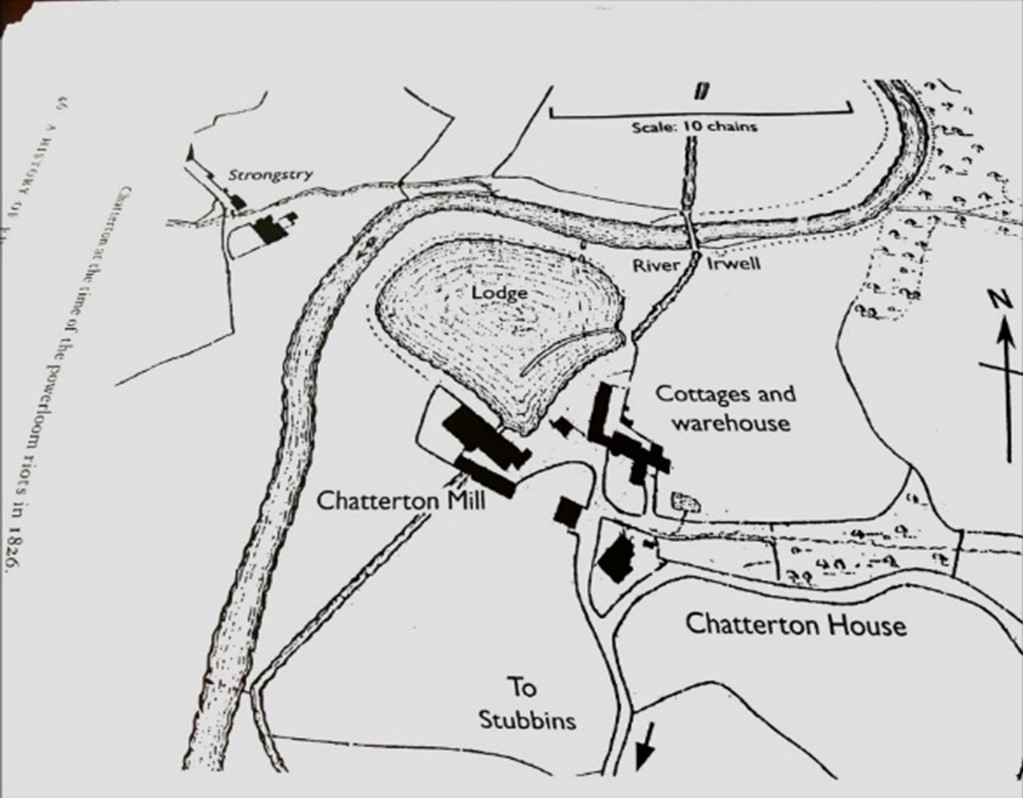

Those defending the mill, under the leadership of Colonel Kearney, comprised of both cavalry and riflemen from the British Army. Under Kearney’s command were 15 Queen’s Bays cavalrymen, in their famous red uniforms and black hats. As the large crowd descended upon Chatterton, the Queen’s Bays made their way to the hill behind the cottages opposite the mill and awaited further instructions.

The Queen’s Bays by Michael Angelo Hayes

Also at Kearney’s disposal were 20 Riflemen from the 60th Duke of York Own Rifles. Dressed in dark green uniforms, these were highly trained sharp shooters with long range Baker rifles. The 60th Rifles were also experienced in close combat skirmishers.

60th Duke of York Own Rifles by Charles Stadden

Under the orders of Colonel Kearney, the 20 riflemen lined up in two ranks of 10 at the bottom of Chatterton Old Lane, just outside the house of the mill owner, and opened fire. The soldiers fired 600 bullets into a crowd of 3,000 people over a period of 15 minutes. Clearly, many of the soldiers deliberately aimed to miss, perhaps shooting into the ground, into the brickwork of the mill, warehouse and cottages or over heads of the protestors. At least four people were seriously wounded although the exact number of those shot remains unknown, including the number (if any) who later died of their wounds. What is known is that during this sustained volley of 600 bullets four people were shot and died immediately or very shortly afterwards.

Indiscriminate State Killings

The first person who was killed was James Lord, who was shot in the back of the head after throwing a stone at a Colonel Kearney. Shortly afterwards soldiers fatally shot John Ashworth and James Rothwell, who both died instantaneously. Undeterred by the shootings, the crowd continued to break into Aitkens and Lords factory and successfully destroyed all the powerlooms within. However, Richard Lund, who was attempting to make his escape out of the back of the factory through a window was also fatally shot. He managed to crawl in agony across the river Irwell but died moments later on the other side of the riverbank.

Some of the protestors were carrying wounded, some of them were wounded themselves. The mill owner by this point had fled with his family and soldiers from the 60th Duke of York Own Rifles were now in skirmisher mode as they attempted to disperse protestors and bystanders gathered in and around the mill. Around 200 protestors were dispersed in the direction of Stubbins and Ramsbottom, and these protestors continued in their attempts to destroy powerlooms along the banks of the Irwell, most notably at mills in Higher Summerseat and in Elton, Bury. The remaining 2,000 and more protestors were also successfully dispersed by the soldiers and cavalry, before making their way back towards Rawtenstall where they regrouped and continued their quest in the mills along the road towards Bacup.

Map of Chatterton Mill in 1826, cited in Simpson (2003)

But this wasn't the end of the killings. What happened as the crowd dispersed demonstrates that this tragedy should, without question, be referred to as a massacre (rather than a ‘riot’ or ‘fight’). The soldiers’ actions resulted in two further indiscriminate killings. Behind the Chatterton cottages, many people had gathered to watch and, for the vast majority, encourage the powerloom destruction. One of the people gathered was a 23 year old woman called Mary Simpson, who had made her way to Edenfield that morning to catch the coach to Manchester. However, because of the size of the 3,000-4,000 strong crowd earlier that morning she was delayed and the coach to Manchester had left without her. Whilst waiting for the next coach she had decided to go down and see what was happening in Chatterton. As the soldiers made their way onto the hill to disperse the crowd she was shot in the thigh, possibly by a stray shot or a ricochet, and bled to death. Mary Simpson was merely a bystander with no involvement in the uprising, yet the army claimed in the days following the massacre that she had been actively involved in the protests. This ‘negative reputation’ was spread to justify her killing, but there were sufficient people with knowledge of her interrupted journey to Manchester to successfully rebuke such blatant lies.

There was to be one further indiscriminate killing at Chatterton on the morning of 26th of April 1826. This was the death of a man called James Whatacre. Before the protesters had arrived in Edenfield, James Whatacre had been at Dearden Clough Mill where, in the interests of the mill owner, he had helped take off some of the wraps of the powerloom to save them from being destroyed in the uprising. James Whatacre, with his friend Richard Leech and then walked down to Chatterton and were hiding near to the cottages opposite the Aitkens and Lords Mill when, for some reason, Whatacre thought he would be safer to try and get into No. 12 Chatterton Cottages, the dwelling of Mrs Upton. As James Whatacre was banging on the door of Mrs Upton's house, he was shot dead at close range by one of the British soldiers.

.jpg)

The Murder of James Whatacre, cited in Turner (1992)

Whatacre bled to death on the doorstep and died from his wounds a few minutes later. Leech ran away. The soldiers ignored Whatacre. They stormed into the house, grabbed a protester who was hiding upstairs under Mrs Upton’s bed and then left with their captive. On leaving No. 12 Chatterton Cottages, the soldiers walked over the dying body of James Whatacre without offering any assistance.

The Response of the State

The response of the state to Chatterton and the wider problem of food poverty in east Lancashire was not acknowledgement of the very real threat of mass starvation but to punish the people involved in the uprising. This punitive mentality can be witnessed across the state response, from the demands of the then Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel, that none of the protestors should receive any of the charitable relief organised in London from May 1826, through to the harsh punishments received by protestors at the Lancaster Assize later in the year. Thomas Ashworth, who was one of the protestors in the uprising, died on the 26th of September 1826 from a ‘visitation of God’ (heart attack) after receiving the death penalty for his part in the uprising. A total of 41 protestors received the death sentence, and whereas 31 of those were later commuted to prison sentences, 10 people who were part of the crowd during the uprising, including the local woman Marry Hindle, were transported to Australia.

Mary Hindle, who had been arrested on day two of the uprising outside of William Turners’ mill in Helmshore, was not directly involved in the powerloom destruction. She insisted she was looking for her six year old daughter who had travelled to Helmshore from Haslingden to witness the protests at Turners’ Mill. Although it is likely Mary Hindle gave some encouragement to those breaking powerlooms, she was merely one of many who did so, as the whole community of east Lancashire was in desperate need and understandably very supportive of people doing something to send a message about the already deadly consequences of starvation and other related illnesses. Mary Hindle was transported to New South Wales and several years later she took her own life on hearing that her family back home had died. Tragically, the death toll in east Lancashire due to starvation and related illnesses was continue for long after the massacre and prosecutions.

Widespread knowledge of the truth of the Chatterton Massacre was something that the government and the army tried to close-down as quickly as possible. The inquest into the six deaths was held the following day on the 27th of April 1826 in Edenfield. No members of the press were allowed to attend. This exclusion was incredibly significant because many of the local east Lancastrian people, and the local handloom weavers, were poorly educated. The handloom weavers did not have a lot of reading and writing skills and long narratives and testimonies of their lives or biographies are rare. The weavers and their families were focused on day to day survival and eking out an existence in very difficult economic circumstances. However, one of the places historically where the views of ordinary working class people were given a public voice was in the corners court. Hence it is profoundly significant that this avenue for their voice to be heard and amplified by the media was in effect closed-down.

The coroners court came to the three different verdicts with regards to the people shot by the soldiers. The first four deaths, James Lord, John Ashworth, James Rothwell and Richard Lund, were given an inquest verdict of ‘shot as part of the mob’. The verdict for the death of Mary Simpson was ‘accidental death’ but the death of James Whatacre was considered as ‘murder by an unknown soldier’. It seems that some local people knew who the soldier was, but this was never fully investigated by the coroner’s court. Within weeks of the inquest’s conclusion the 60th Duke of York Own Rifles were redeployed to Portugal and with it the ending of any further scrutiny into their actions.

Perhaps though most illuminating following the Chatterton massacre was the absence of any prosecutions of protestors at the 1826 Lancashire Assize (there was one prosecution brought against someone from Chatterton in 1827, but this person was acquitted). At virtually every other site of the uprising criminal charges were laid, but there were none from Chatterton in the year of 1826. This raises questions about the justification given for the shooting at the time – that the soldiers feared for their lives and that the unruly ‘mob’ was out of control and a threat to life as well as property and thus were required to dispense more than 600 bullets.

Yet if the crowd were out of control at Chatterton, why were there no criminal prosecutions? If the crowd had become so dangerous that the very lives of the soldiers were under perceived to be under threat, why were the no significant recorded injuries to the soldiers? Why were all the people who died or seriously injured from the crowd? It can be reasonably assumed that the reason why there was no criminal prosecution was because nobody in a position of power wanted an alternative narrative or definition of events to that proposed by the state platformed. The Lancaster Assize would have been another opportunity for the local people to give their side of the story. A criminal court case was an important avenue for testimonies from ordinary people to be recorded and may perhaps have led to an interpretation of events that contradicted that of the state.

Britain’s Hidden Massacre

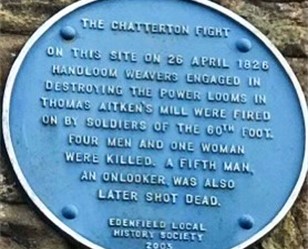

The deadly events at Chatterton on the 26th of April 1826 are still often described as a ‘riot’ (including descriptions in local council leaflets) or a ‘fight’ (including the official Blue Plaque commemorating the deaths) rather than a massacre. Yet neither ‘riot’ nor ‘fight’ can adequately convey the deadly nature of events that day nor the indiscriminate way in which at least six people were killed.

Referring to an event as a ‘riot’ implies an instance of collective, public violence by an unruly an ill-disciplined group of people. Even though the use of the term ‘riot’ had a more sympathetic meaning in the nineteenth century, today it implies moral condemnation and blame. Given the account above, to describe these events as a ‘riot’ is to completely invert reality. It was not the crowd who deployed deadly violence, but the state. To call this the ‘Chatterton Riot’ is to invisibilise the terrible truth that at least six people were shot dead. It erases the memory of those who died and obscures the motivation of the people involved, who were protesting to highlight a very real threat of mass starvation.

The Blue Plaque at Chatterton

To call this the ‘Chatterton Fight’ also hides the brutal reality of state violence. A fight implies a mutual exchange of blows, but, at least in terms of serious injuries and death, what happened at Chatterton was very one sided. The only adequate way to refer to what happened is to call these indiscriminate killings for what they are: a massacre. The categorisation and dominant interpretation of what happened at Chatterton on the morning of the 26th of April 1826 is an ideological construct that reflects power relations. To call this a fight or riot is to see through the eyes of the state. The weavers – impoverished, illiterate and without either powerful allies or any collective institutions to argue their case – had much less power and influence than those in authority.

The definition of indiscriminate state killings as massacre largely depends on whether it is defined as such as the time and whether those advocating this interpretation can muster enough influence and political forces for it to take hold and become part of the public conscience. Back in 1826 or indeed many of the years following, no such political forces were mobilised. Consequently, the events are Chatterton are not officially named as one of the massacres in this country. The indiscriminate killings at Chatterton 196 years ago are then, in effect, Britain’s’ hidden massacre. This must change.