Corporate Killing With Impunity

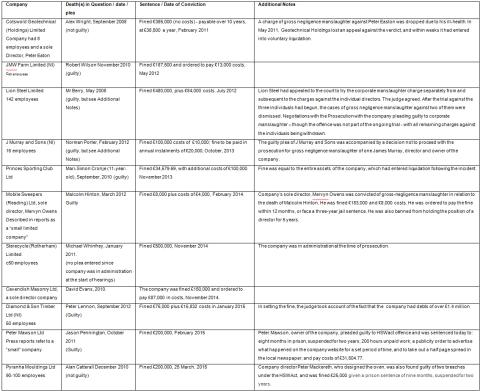

Table 1. Convictions under the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act, 2007

This week saw sentence passed following the eleventh conviction under the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act, 2007 (CMCHAct). Pyranha Mouldings, a small kayak manufacturer, was fined £200,000 following the death of a worker in 2010. Allan Catterrall had been trapped and died in an industrial oven.

The Act, rolled out across the UK seven years ago to improve accountability for corporate killing, has so far failed dismally to undermine what is essentially corporate impunity for deaths at work. Part of this failure has its roots in the Act itself, namely the exemption guaranteed to senior managers and directors in section 18, titled “No Individual Liability”. Indeed, it was only after this exemption was inserted by the Government during the legislative process that widespread business opposition to the proposed law became muted.

In England and Wales and Northern Ireland, the common law offence of gross negligence manslaughter still exists as a mechanism to hold individuals to account for their part in corporate killing, while in Scotland there is an equivalent common law offence of culpable homicide. However, there is some evidence that one effect of the CMCHAct is that in England and Wales (there have so far been no convictions in Scotland), individual liability has been sacrificed for pursuing corporate liability. In three of the first four convictions (see Table 1), decisions to proceed with corporate manslaughter prosecutions were accompanied by decisions not to proceed with charges against individual directors for the offence of gross negligence manslaughter.

Thus, some legal commentators have already referred to a nascent trend, with the threat of charges against individual directors being the ‘bait’ for a corporate manslaughter charge: ‘an offer from… the company to plead guilty in exchange for the prosecution dropping charges against individuals might look like an attractive one to a director facing a risk of prison’.

Moreover, further scrutiny of these convictions reveals two additional, key failings of the law.

First, all of the companies successfully prosecuted thus far have been small or medium sized enterprises which could have been successfully prosecuted under the common law of manslaughter (see Table 1). Thus, the large, complexly owned companies for which the new law was ostensibly designed, have so far evaded its reach. Perhaps relatedly, all of the convictions secured to date relate to offences involving a single fatality – while a key intention behind the law was to encompass multiple fatality incidents.

Second, the level of fines passed at sentencing has been relatively low. Following the passage of the CMCHAct, the Sentencing Guidelines Council had issued ‘definitive’ guidance on determining appropriate levels of penalties following successful prosecution under the Act. These guidelines marked ‘a very considerable backstep’ from a [2007] draft guideline, which had proposed that fines should be calculated within a percentage range of company turnover. The ‘definitive’ guidelines removed any link with turnover, with the key rationale for setting the level of fine being the ‘seriousness of the offence’ and factors contributing to this. Calculated in this way, fines should ‘be punitive and sufficient to have an impact on the defendant’, so that the ‘appropriate fine will seldom be less than £500,000 and may be measured in millions of pounds’. In fact, and as Table 1 indicates, only one fine has so far reached this putative minimum – although it should be noted that the fine of £500,000 was imposed upon a company which at the start of the trial was in fact in administration (Sterecycle [Rotherham] Ltd). Interestingly, a recognition of the poverty of current sentencing practice under the Act has prompted a new set of draft guidelines, currently under consideration, in which it is proposed that there be a more explicit link between fines and turnover – although the proposal is focused on larger sized companies, none of which have yet been convicted.

Each year in the UK, up to 50,000 workers die from fatal injuries and work-related illnesses, of which a significant but unknown proportion are likely to be the result of legal breaches by their employers. This annual total ranks highly in comparison with virtually all other recorded causes of premature death in the UK, and dwarfs the just-over 600 ‘conventional’ murders recorded in the most recent figures across the three jurisdictions of the UK. Such observations alone make the rate of convictions under the CMCHAct look like a spectacular failure on the part of police forces and the Crown Prosecution Service. The CMCHAct is beginning to look very much like another weak, and at best, symbolic attempt to hold to account companies which kill – one which barely dents the impunity which corporations continue to enjoy as they put profits before human lives.

Steve Tombs, The Open University