You are here

- Home

- Blog

- Do techniques for generating suspects contaminate procedures for identifying perpetrators?

Do techniques for generating suspects contaminate procedures for identifying perpetrators?

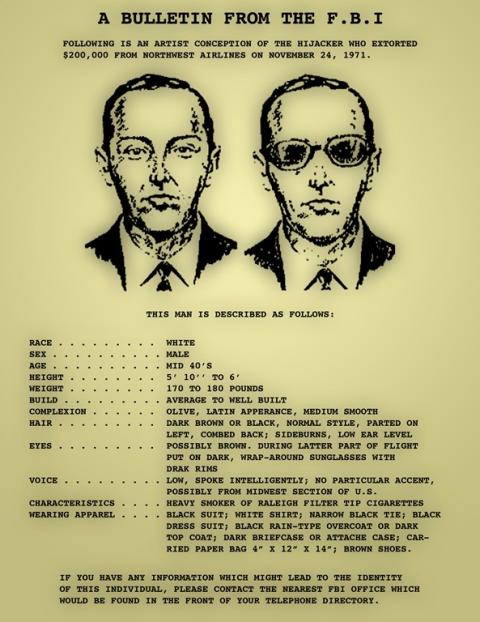

Français : Gouvernement Fédéral des Etats-Unis English: U.S. Federal Government [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

There is considerable evidence that mistaken identification by an eyewitness is the leading cause of miscarriages of justice. For example, research done by The Innocence Project, has found that eyewitness misidentification plays a role in more than 70% of overturned convictions and is the single greatest contributing factor in wrongful convictions. So, what should we do? Abandon eyewitness evidence because it is too unreliable? As tempting as that might be, think of all the victims who you then also abandon by refusing them access to justice. Rely solely on forensic evidence maybe? Nice idea, but in reality, forensic science is not like it is in CSI TV shows. For one thing, it is used in only a small percentage of cases and estimates suggest that in only about 2% of criminal cases does forensic science link a suspect to the crime scene or victim (Peterson, Sommers, Baskin & Johnson, 2010). For another thing, The Innocence Project estimates that the misapplication of forensic science is itself a major contributing factor to miscarriages of justice (indeed is second only to eyewitness misidentification), and features in about 45% of cases involving a later exoneration.

Some crimes are captured on camera, and in those cases investigators may have an accurate and reliable record of what happened (e.g. car dash-cams may show evidence of dangerous driving, public CCTV cameras may be used to track the movements of terrorist suspects when preparing for an attack). However, unless advances in technology bring us into a world of total surveillance (and assuming we, as citizens, would accept such a world), the criminal justice system will always need to make use of eyewitness evidence to provide access to justice for victims of crime. Obviously, we can try to improve the situation by making sure law enforcement agencies are aware of the risks involved in obtaining evidence from eyewitnesses and use the most appropriate, evidence-based techniques. For example, in the UK, Code D of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 sets out evidence-based practice guidance for identifying suspects, which is periodically updated in light of new research.

A key issue is that we know from psychological research that human memory is not like computer memory, which perfectly stores whatever is put into it until it is later needed. Instead, human memory is a dynamic and changeable construct that is based on extracting meaning from the world around us, which means our memories are subjective and dependent on who we are. Importantly, this means that our memory for an event (such as a crime) is likely to change if we are later exposed to information about that event (known as ‘post-event information’), which is why it is common practice to separate witnesses so that they cannot share accounts.

Post-event information can come in many forms, including the questions posed by law enforcement officials, who can change a witness’s memory by asking a leading question (for example, asking ‘what colour coat was he wearing?’ may cause a witness to form a false memory of the suspect wearing a coat when in fact they were not). Showing a witness images of possible suspects (in a mugshot album for instance) is a particularly problematic form of post-event information because it is possible that the witness will ‘unconsciously transfer’ one of the images into their memory of the perpetrator – meaning they may then pick that person out at a line-up. You can find out more about unconscious transference in week 6 of our free online forensic psychology course (or click here to access the whole course from the beginning and explore a wide range of issues in forensic psychology).

One solution to the problem of post-event information could be for law enforcement to limit exposure to it by limiting their interaction with the witness, perhaps only involving them in the investigation to provide key evidence such as a statement and to attend a line-up or other identification procedure. Although that might be feasible in some cases, what about if the police do not have a suspect? In some cases, it could be that the only way the investigation could progress would be to ask the witness to create a facial composite (e.g. Photofit or E-FIT) that can be used to seek help from the public. However, these techniques involve showing the witness faces or computerised face-images during the composite process. Could this introduce post-event information which might contaminate the memory of the witness and therefore the evidence they could provide (i.e. identifying the suspect later on, once an arrest is made)? In essence, the question is whether the methods used by law enforcement to generate a suspect might then contaminate the evidence needed to prove in court that the suspect is indeed the perpetrator of the offence.

This was a question we sought to answer using the ‘mock investigation’ paradigm, in which participant-witnesses are shown a staged crime and then asked to provide evidence by researchers (who take the place of law enforcement officers) in the form of statements and through identification procedures. We were particularly interested in whether creating a facial composite image would interfere with the witness’s memory and make their decision at a subsequent identification procedure less accurate. Previous research in this area had tended to produce equivocal results, with some studies showing a detrimental effect and some not. However, the prior research had typically used quite an artificial approach in which undergraduate students (often psychology students taking part in experiments for course credit) were first shown a video of a crime, created a facial composite either by themselves or with a researcher and then, often immediately or after a short delay, attempted to identify the perpetrator in a photo line-up. Although such procedures are very useful, as they explore the underlying human cognition and performance in a very controlled setting, there are some obvious differences with the experiences of a real witness. In other words, existing research largely lacked ecological validity.

Given how high the potential stakes are in evaluating criminal investigation procedures, our research attempted to be as ‘real’ as possible. To this end we (1) used ‘live’ staged crimes (not a video), which were (2) seen by witnesses from a much more diverse range of backgrounds than typical undergraduate students, who then (3) worked with a police officer (in our Experiment 1) or a researcher who was an experienced composite operator (in our Experiment 2) to create a facial composite using the software and procedures that would be used in a real case, before (4) being shown an identification procedure 4-6 weeks later (the average time taken in reality). We also employed both photo line-ups (as used in the USA) and video identification parades (as used in the UK). Our results showed that, compared to a control group that did not create facial composites, creating a facial composite did not appear to adversely affect the decision made at a subsequent identification procedure. If you would like to read the full details of our study, you can access a copy of the paper from the Open University’s Open Research Online repository here: Pike, Brace, Turner and Vredeveldt, 2018.

As noted earlier, the results of prior research were equivocal – although, anecdotally, many researchers and legal practitioners seem (perhaps understandably) inclined towards a principle of caution, favouring the research that there is a detrimental effect of composite construction on subsequent identification. Our results support the existing body of research that suggests composite creation does not necessarily contaminate the memory of a witness, though obviously given the high stakes here great care needs to be taken in applying research results to practice. It is also important to note that research tends to deal with trends and averages, which can be problematic for operational practice which has to make decisions about a single witness.

However, and in conclusion, we think there is a useful take home message here about the importance of balancing the needs of the victim and the needs of the suspect. We have to realise that a human criminal justice system will never be perfect and, as unpleasant as it sounds, that means balancing the need for access to justice for victims with the need to avoid wrongful convictions. Attempts to address one of these problems may concomitantly, albeit inadvertently, increase the other. We do not, of course, claim to have solved this problem. However, the potential risk that creating facial composites will contaminate the witness’s memory does not seem to be a concern under realistic experimental conditions. We therefore think that this is a risk it might be worth taking if there is no other way to progress the investigation.

Graham Pike and Jim Turner, The Open University.