You are here

Fortresses of Iron Coffins: Prisons in England and Wales in Historical Context

While prisons have been in existence since at least Egyptian times, it was only in the late 1700s that prisons were proposed as places of rehabilitation in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US). At that time, utilitarian philosophers like Jeremy Bentham and Christian evangelicals, like John Howard in the UK, alongside prison reformers like Benjamin Rush in the US, proposed that prisons could be conduits for radically changing individuals for the better. At around this time there were also prisons being built in European (including British) colonies. However, as everyday life in colonial societies was characterised by coercion, repression and violence, colonial prisons were primarily conceived to punish and control political dissent and the resistance of indigenous populations and slaves rather than act as conduits for personal or spiritual transformation. By the mid-late 1800s, the ideologies and practices of the British colonial penal system undoubtedly started to have influence on penal policy in England and Wales. This influence coincided with a fundamental questioning of the rehabilitative assumptions of the new ‘reformed prisons’ (as Peter Kropotkin famously called them) and the growing prominence of people with direct experience of the British colonial penal system in the UK prison administrations. However, at the end of the 1700s, where our story begins, for their Christian and utilitarian advocates, the new ‘reformed prisons’ were considered places that could instil moral fibre and moral backbone, thus remaking a criminal personality into a law-abiding one.

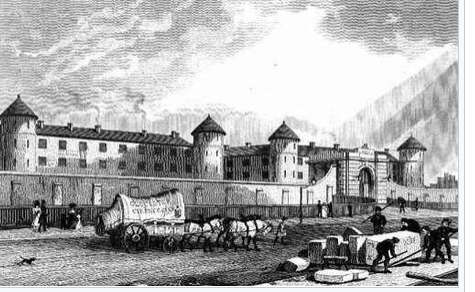

Utilitarianism assumes people avoid pain and maximise pleasure. For Bentham, if punishment was made unpleasant enough to outweigh the pleasure of a given crime, a scientific way of ensuring the conformity of the human psyche could be established. These two very different traditions – Christianity and utilitarianism – thus fused together as the joint justification for a new institution of pain and suffering: the penitentiary. Jeremy Bentham wanted to create a new super surveillance machine - what he called the Panopticon - to be designed like a spider's web, where a superintendent could sit at its centre and watch, observe, discipline and control those within their sight. Though Bentham spent years trying to establish such a private prison in the UK, in the end it was a state-run prison that was opened at Millbank, London in 1816. It was called the ‘General Penitentiary’.

The Rationale of the Reformed Prisons

That the early reformed prisons were called ‘penitentiaries’ gives us a significant insight into their Christian underpinnings. The explicit goal of the prison was to force offenders to be penitent. People were sent to the prison to repent and reflect upon their own individualised problems. The early penitentiary initiatives in the UK and the US, however, were an absolute and total humanitarian disaster. They just didn't work. At the General Penitentiary in Millbank, for example, there were major disturbances almost immediately after the first women prisoners were incarcerated there in 1816. Then, a few years later with the introduction of a chaplain governor - Rev Daniel Nihill - the warders and turnkeys (what we now call prison officers) read scripture to the then male prisoners which the prison housed. Rev Nihill believed that to be effective conduits for redemption, prisons had to tough and austere. Writing in his book Prison Discipline in 1839 he argued that “Prison fare, ex vi termini, should be reduced far below that which falls within the reach of the honest and industrious”.

If it be found by the visits of strangers, or the intimations made to friends, that the food and clothing; the cheerfulness and warmth; the medicine and diet, and accommodations in time of sickness; the shelter and the bedding, and various other comforts enjoyed by convicts, present a luxurious contrast to the miseries of the honest labouring class, the effect must be to strip imprisonment of its awful character, and to give rise to many recommitments.

Reformed prisons were to be basic, bare and brutal, but initially, at least, they were also intended to rehabilitate through imparting knowledge of the ‘great redeemer’ to the wretched sinners they contained. Prisoners were held in solitary confinement and were taken every single day to the chapel to hear the chaplain preach to them for an hour about their sins. When the ‘less eligible’ prisoner was placed into their individual box in the General Penitentiary chapel for their daily sermon, they were unable communicate with anybody else and had to listen passively to being told how immoral and unworthy they were. No mention was made of poverty, social inequalities or the social harms generated by the rich and powerful. Rather, the focus was upon punishing a group of relatively impoverished people who were placed in an institution based on moral force and discipline to ‘win the heart’ and change for the better. Yet ultimately the General Penitentiary was a social experiment which resulted in misery, hardship, massive ill health (both physical and mental), and death. It led to a number of people taking their own lives or losing their minds. It was an absolute and total fiasco.

Hard labour, hard fare, and a hard bed

Despite the abject failure of the General Penitentiary, the prison experiment continued. For example, in the 1840s HMP Pentonville in London opened, and the reformation of the offender was once again at the centre of the penal regime. The prison chaplain was charged to instil virtue and moral backbone to prisoners, but like the earlier efforts in Millbank this not only failed to positively change people but also had harmful and negative consequences. Though prisons continued to house thousands of people, by the 1860s there was recognition that prisons were unable to harness the transformative power of the cross, leading to virtual abandonment of the original rehabilitative mission. The mantra of new penal regime in convict prisons entered common parlance as “‘hard labour, hard fare, and a hard bed’”. Under the stewardship of Sir Edmund Du Cane the prisons were now all about general deterrence. Du Cane had been involved in the organising of convict labour in the Swan River colony, Western Australia from 1851 to 1856 and the more coercive and oppressive practices of the colonial prisons, which were largely about hard labour, servitude and physical punishment, undoubtedly shaped his penal philosophy. Du Cane wrote in his book The Punishment and Prevention of Crime in 1885 that the “object of the penal element is more to deter others than for the effect on the individual subjected to the punishment”.

If by punishing those who have an incurable tendency to crime we can deter fresh recruits from joining the ranks of the criminal class, the objects of punishment is effected; and obviously if we could possibly arrive at the result that all convictions were reconvictions, and none of them first sentences, we should be in a fair way of putting an end to crime altogether.

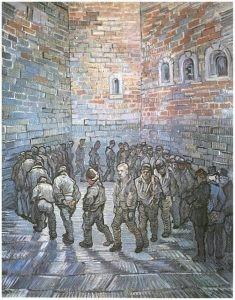

Because most prisoners were considered to be hereditary criminals of a “low moral type” they were now regarded as irredeemable. There humanity was contingent rather than the universal brotherhood of Christianity. For Du Cane, prisoners were people of “diseased and impaired constitutions, victims of dirt, intemperance, and irregularity, and the sins of the father in these respects are visited on the children”. For such prisoners the daily regime was now all about punishment, discipline and monotonous labour. The aim was to ‘grind rouges good,’ making ‘lags’ work really hard, by putting them on the treadmill, giving them a crank to turn, or various other forms of totally useless labour.

A Disciplinary Machine

Nineteenth century prisons in the metropole were influenced by British colonial penal ideas and practices, and indeed, by the penal ideas and practices of former colonies. In the US, a penal leader even in the early days of the reformed prisons, and then shortly later in the UK, two different forms of penal discipline developed from the early 1800s onwards. The first was the ‘silent system’, where prisoners were allowed to associate when working but not to speak. The second was the ‘separate system’, which involved the social isolation of prisoners and their silence. In the latter system, prisoners were kept completely separate so there could not be any associations between incorrigible criminals. There was considerable debate throughout the 1800s as which system was best, but despite their cruelty, neither of them actually worked. By the 1920s prisoners in England and Wales were allowed to speak to each other and it was recognised that silence/separation was profoundly damaging for people. People are intersubjective beings who rely upon and require the engagement with other humans to maintain a sense of reality and overall wellbeing. Making prisoners lead solitary lives resulted to the unravelling of the self. The penitentiary, as a fortress of iron coffins, was soul destroying. They were nothing more than harm creating tombs of the living.

The prison, certainly by the late 1800s, was increasingly characterised by structure, discipline, control and uniformity. If the prison in the early 1800s had taken some inspiration from the monastery, seventy and more years later it was also taking inspiration from the military barracks. Another undoubted influence on prison discipline at this time was the industrial factory. One argument often made about the history of the prison is that the highly regulated and timetabled discipline of penal regimes, and its mirroring of military and religious discipline, was intimately connected to the increased emphasis on work-based discipline. Philosophers, such as Michel Foucault, have argued that the evolution of prison discipline should be situated within the development of a much more disciplinary society. This thesis situates the birth of the prison within the developments of a capitalist mode of production and as part of a wider strategy to ensure the working class were disciplined enough so they turn up for work on time and become productive and efficient workers.

Enlightened Voices

Voices against the ‘reformed prisons’ should also be situated within historical context. Abolitionists, such as Peter Kropotkin, railed against the inhumanity of penal regimes from the 1880s onwards. He was not alone. Some of the most plausible and convincing arguments against the prison from the late 1800s and early 1900s came from people within the system. Those imprisoned, those who walked the landings, or those were involved in the administration of the prison system were highly critical if not totally damning of prison regimes. These enlightened voices - voices of reason and knowledge – can be found official reports as well as in a great many prisoner and prison staff autobiographies. Let us here though contrast to pro-prison arguments of people like Nihill and Du Cane, with voices of critique and dissent from penal administrators such as Lushington and Paterson.

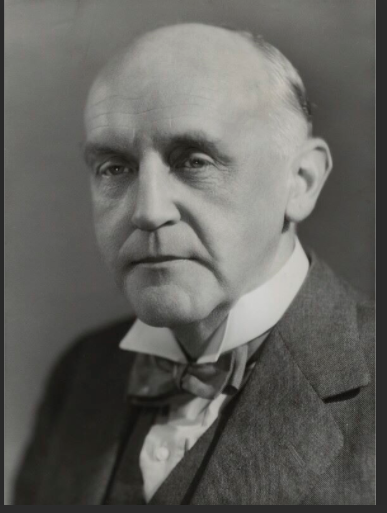

By the 1890s, which saw the end of the Sir Edmund Du Cane disciplinarian reign, the harms of imprisonment were starting to become increasingly visible to the general public. Voices from within the government itself start to argue that prisons were failing. One of the most notable critiques came from Sir Godfrey Lushington, who was the Permanent Secretary of the State for the Home Office in the UK from the 1880s through to 1895. In his evidence to the House of Commons Report from the departmental committee on prisons, Lushington stated:

I regard as unfavourable to reformation the status of a prisoner throughout his whole career; the crushing, of self-respect, the starving of all moral instinct he may possess, the absence of all opportunity to do or receive a kindness, the continual association with none but criminals, and that only as a separate item amongst other items also separate; the forced labour, and the denial of all liberty. I believe the true mode of reforming a man or restoring him to society is exactly in the opposite direction of all these; but, of course, this is a mere idea. It is quite impracticable in a prison. In fact, the unfavourable features I have mentioned are inseparable from prison life.

For Lushington a prison sentence was never going to lead to reformation. But he isn't the only person from within the system who had an enlightened sense that something was very wrong. Perhaps the most influential reformer of prisons at the beginning of the 20th century was Sir Alexander Paterson. Paterson, the leading prison commissioner, famously established the ‘Borstal regime’ in the early 1900s. Borstal was an institution for children modelled on Eton public school, and took its name from the village in which it was established. Paterson called for decent education and recognition that the deprivation of liberty was punishment in its own right. For Paterson, prisons were ultimately a “sentence of living death” and a place which could “so easily become an unhealthy little cesspool”. By the time he got to the end of his career, Paterson went as far as to suggest a civilised society should abandon the idea of calling state-institutional-confinement reform prisons or penitentiaries. For Paterson there should exist places that can house people for psychiatric diagnosis and to help with people with mental health problems. He also argued that that they should be institutions that aim to train and educate those who have lost their way. But most importantly he argued state-institutional-confinement had to be a place of non-punitive detention.

When Lushington and Paterson were at their peak of powers there started a quite radical reduction in prison populations. Though there was to be no end of the prison, from the beginning of the 1900s through to the 1930s, there was de-escalation of prison sentences in England and Wales. There was recognition at this time that there was something very wrong with prisons. But it wasn't just by people like Lushington and Paterson. This was also a time when there were a number of very wealthy women suffragettes spending time in prisons. One example was Lady Constance Lytton, sister-in-law of a former liberal prime minister. Lytton was imprisoned as a suffragette, both under her own name as Lady Constance Lytton but also under the false name as commoner Jane Warton. Lytton/Warton went on hunger strike and was brutally force fed whilst in prison. It nearly killed her. For Lytton the “horrors of prison existence are enshrined in an atmosphere of nightmare”. In fact, she wrote her autobiography Prisons and Prisoners: Some personal experiences of a suffragette in 1914 following a stroke as a result of her imprisonment.

For Constance Lytton, prisons were cold and harsh institutions that crushed the life out of both keepers and the kept. When writing about the ‘wardresses’ (the name of women prison officers at that time) she wrote:

I noticed that there was no inflection in the voice when speaking to prisoners, nor did the wardresses look at them when addressing them. As a prisoner, it was almost impossible to look in the eyes of my keepers, they seemed to fear that direct means of communication; it was as if the wardresses wore a mask, and withdrew as much as possible all expression of their own personality or recognition of it in the prisoner.

.jpg.png)

The inhumanity bred in the prison place was not just experienced by prisoners such as Lady Constance Lytton. In addition to imprisoned suffragettes, there were also conscientious objectors to the First World War who were given long prison sentences as well as people imprisoned for their socialist activism. This led, for example, to Fabian socialists documenting both the history of prison (as charted by Sydney and Beatrice Webb) and the harms of imprisonment in the early 1920s, notably in English Prisons Today: Being the Report of the Prison System Enquiry Committee (compiled by Stephen Hobhouse and Fenner Brockway). Alongside these writings, there was testimonies of people imprisonment until the 1950s because of their sexuality, with perhaps the writings of Oscar Wilde in the 1890s being the most well remembered today.

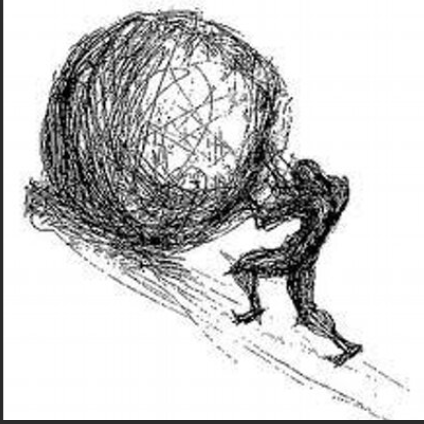

The Myth of Sisyphus

In the early 1900s people from middle-class backgrounds, were, for the first time in the history of the ‘reformed prisons’, finding themselves in large numbers behind bars. This knowledge and direct experience led to the development of a bad conscience about prisons, where people from all walks of life recognised that prisons did not work. Indeed, by the 1960s there was genuine talk of abolishing prisons in political circles in the US ad UK. Whilst the crisis of capitalism, the gradual unravelling of the welfare state and the ratcheting up of what Peter Kropotkin calls a ‘law and order society’ put paid to such talk among penal authorities and the middle classes in 1970s, the lesson from history is perfectly clear: prisons are harmful places which do little good.

There is no historic picture to be painted of a ‘golden age’ we can hark back too of truly effective and humane prisons. A more telling image of our current predicament would be that of Sisyphus rolling his bolder up a hillside only to find when he reaches the top that the bolder will automatically roll back to its starting point. Are we forever doomed to repeat the same mistake of housing (impoverished) lawbreakers in fortresses of iron coffins or is our society collectively prepared to do something radically different and end the disastrous 200-year experiment of penal incarceration?

Dr David Scott (@dgscott2) will be talking about prison history in an interview on the BBC Radio 4 Programme ‘Prison Break’ (episode 4, How did it come to this?) on May 14th, 2021. To listen to this episode, see: