You are here

International Workers’ Memorial Day (#IWMD25): Confronting the Deadly Cost of Work

Each year on 28th April, across the globe, workers gather to remember the dead. Not soldiers. Not politicians. But people who died simply because they went to work.

In Britain and beyond, work kills. Quietly. Predictably. Systemically. And far too often, invisibly.

As the rallying cry of International Workers’ Memorial Day (IWMD) reminds us, “Mourn for the dead. Fight for the living.” This is more than a memorial— it’s a demand for recognition, accountability, and action in the face of preventable harms.

Image Credit: Created using Canva's Dream Lab by Sharon Hartles, using Text-to-Image feature.

International Workers' Memorial Day (IWMD) exists because our societies continue to treat workplace death, injury, and disease as unfortunate accidents—when in truth, they are foreseeable outcomes of how we organise work under capitalism.

Workplace death, injury, and illness are not only matters of life and death, but of enduring, multi-dimensional harm—economic, physical, financial, emotional, and psychological. And while fatalities are the most visible and devastating outcome, it is the slow grind of harm—the pain, the stress, the long-term sickness—that affects millions and lays bare just how violent our work systems truly are. The multi-dimensional nature of workplace harm is too often ignored in official statistics and legal frameworks, yet it is deeply felt in the lives of those left behind.

The cost of work isn’t just measured in the hours worked or the wages paid. It’s counted in blood—the blood of workers who, like so many before them, paid with their lives for the luxury of an economy built on their backs.

Let us be clear: the deaths of workers are not caused by freak misfortune. They are caused by corner-cutting bosses, toothless regulation, casualised labour, and the institutional indifference of the state. These are structural harms, not natural disasters. And far too often, they are intentional. The daily brutality of work, and the deaths that come with it, are not just collateral damage. They are the by-product of a system that prizes profit over human life.

As the Trades Union Congress (TUC) poignantly points out, "Every year more people are killed at work than in wars. Most don't die of mystery ailments, or in tragic 'accidents'. They die because an employer decided their safety just wasn't that important a priority."

Invisible Harm, Legalised Violence

Consider the UK’s construction industry—where 51 workers were killed in 2023/24 alone. That’s nearly one death every week. In the public imagination, these are ‘accidents.’ But where employers ignore safety protocols to maximise profit, where oversight is gutted and subcontracting is rampant, such deaths are inevitable. They are not accidents. They are organised irresponsibility.

Take asbestos exposure, for example. For decades, workers were knowingly exposed to deadly fibres in shipyards, construction, and manufacturing. The risks were well documented, yet regulations lagged and companies deflected responsibility. The consequences? Tens of thousands of deaths from asbestos-related diseases such as mesothelioma —many long after exposure. Invisible harm. Predictable suffering. Avoidable deaths.

As Friedrich Engels famously stated in his 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England: “When society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and unnatural death… its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual.”

This is not merely a case of unfortunate circumstances, but a form of murder—social murder. These harms and subsequent deaths are a direct consequence of social structures that could be changed but are maintained by those in power.

The problem is not that these deaths are mere accidents; they are the inevitable result of systemic exploitation. Yet, our legal system refuses to acknowledge them as the crimes they truly are. This failure to address workplace deaths as crimes reflects a deep moral and legal blind spot—one that shields those responsible for these deaths while continuing to punish the victims. What the law calls 'accidents' are, in fact to others, social murders. The gap between legal definitions and moral reality is vast, and it’s this systemic failure that we must confront.

David Whyte powerfully remarks: “The collapse in HSE enforcement and prosecution sends a clear message that the government is prepared to let employers kill and maim with impunity.”

This is the true cost of a system that values profit more than workers. When regulations are weak, and enforcement is even weaker, the inevitable consequences become the price of doing business. Workers’ lives are treated as expendable, and the death toll mounts. We cannot afford to let the term ‘accident’ erase the intentionality of these deaths. These are avoidable deaths—deaths that could have been prevented with stronger regulation and the political will to enforce it, instead of being met largely with political silence.

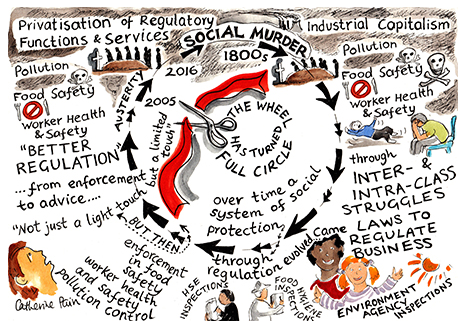

The shift toward ‘light-touch’ regulation or ‘regulatory surrender’ has effectively led to “decriminalised death and injury at work,” normalising fatalities and stripping them of their criminal context. As a result, serious incidents are not only underreported but also often ignored, further entrenching the culture of impunity.

Steve Tombs pointed out, “Violent street crime consumes enormous political, media, and academic energy. But, as hundreds of thousands of workers and their families know, it is the violence associated with working for a living that is most likely to kill and hospitalise.”

The Health and Safety Executive’s (HSE) latest statistics make clear the scale of this violence. In 2023/24, 138 workers were killed in work-related accidents in Britain. A further 604,000 workers sustained non-fatal injuries, and 1.7 million people reported suffering from work-related illnesses. These included 776,000 cases of stress, depression or anxiety, and 543,000 cases of musculoskeletal disorders—harms that extend far beyond the factory floor or office cubicle. Even more starkly, around 12,000 people die each year from past exposures to workplace hazards like asbestos.

And these figures? They are only the ones we know about. The true scale is likely far higher, obscured by underreporting, precarious work conditions, and a regulatory system that too often turns a blind eye. These are not anomalies. They are the predictable, preventable outcomes of a system designed to extract profit and outsource risk—a system where the human cost is hidden, normalised, and too easily erased.

Image Credit: Created using Canva's Dream Lab by Sharon Hartles, using Text-to-Image feature.

Think of the 800 P&O Ferries workers, sacked by video call and replaced by cheaper, non-union labour. It may not have left blood on the floor, but make no mistake: that too is violence. It destroys lives, families, and futures—sanctioned by laws written to protect capital. This is not an isolated case; it’s the pattern of a system that thrives on disposability. The workers who were thrown out without warning, without concern for their livelihoods, are just one example of the dehumanising effect of capitalism. It is a system that turns human lives into expendable commodities, where workers are seen as nothing more than interchangeable parts in the machinery of profit.

And then there’s Amazon—where workers are tracked by algorithm, pressured to meet impossible targets, and often denied breaks. Injuries are routine. Burnout is expected. The warehouse becomes a machine, and the worker a disposable cog. This is violence by design, sanitised by branding and convenience. In December 2021, six workers were killed when a tornado hit an Amazon warehouse in Illinois—forced to keep working through extreme weather, with no proper storm shelter in place. Not a freak event, but the result of a system that puts productivity over people.

Or recall the frontline workers who died from COVID-19, often without PPE, sacrificed to a failing public health response. The deadliest jobs became care work, delivery work, warehouse work. Not because the virus was indiscriminate, but because the most expendable lives were also the most exploited.

These deaths did not arise in a vacuum. They were the result of decades of underinvestment in the welfare state, precarious employment, and the growing casualisation of labour. Workers who were already at risk, who already lacked proper safety protections, were then left to bear the brunt of a pandemic that exposed the fatal flaws in a system that considers profits more important than people.

These are not ‘crimes’ in a legal sense or state-defined notion of crime—but they are devastating social harms, deeply rooted in systems of inequality. To call them ‘crime’ stretches the law. But to not call them out at all? That is a far greater moral failure. What else can we call the preventable deaths of workers sacrificed to profit—if not, as Engels once put it, social murder?

The law is not a neutral arbiter—it is a tool shaped by power. It defines some harm as criminal, while allowing other, deadlier harms to pass unpunished. And so, if we rely solely on legal definitions of crime, we miss the full scale of violence that capitalism inflicts.

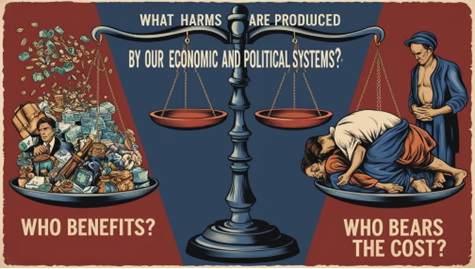

We must ask: What harms are produced by our economic and political systems? Who benefits from them? And who bears the cost? These are the questions that matter—because they shine light on the kinds of violence the law refuses to see.

Workplace deaths are not acts of God. They are the outcome of decisions made by employers, policymakers, and regulators—decisions that are legal, yes, but lethal all the same. We must stop treating legality as the boundary of justice.

A Global Terrain of Harm

But the deadly cost of work is not confined to the UK. Across the world, in different industries and under different governments, workers are suffering and dying for the same reasons: a global economy that treats workers as disposable. In Qatar, thousands of migrant workers died to build the World Cup stadiums.

In Bangladesh, over 1,100 garment workers perished in the Rana Plaza collapse. In South Africa, gold mining has left a brutal legacy. Thousands of mineworkers—often migrants—developed silicosis after years of inhaling dust underground, while mining giants denied liability.

In India, the Bhopal gas leak remains one of the deadliest industrial foreseeable events in history, where over 3,000 people died immediately after a gas leak from a Union Carbide plant, and thousands more have died in the decades since, while the corporation continues to evade full accountability. These are not isolated failings—they are business models built on harm.

These deaths are collateral damage in a global economy built on low wages, deregulation, and disposable labour. The violence is sanitised, hidden behind corporate PR, free trade agreements, and legal technicalities. But the bodies remain. We celebrate progress, technology, and modernity while the price of those luxuries is paid by the people who make them possible—often the very people who never see the benefits of their labour.

In this global terrain, regulatory capture is a key driver of the harm. The industries that profit most from global trade are often the ones with the most power to influence the rules that govern them. Whether through backroom deals, corporate lobbying, or the revolving door between government and business, regulatory bodies are often captured by the very entities they’re meant to oversee. This results in weakened regulations, lax enforcement, and corporate impunity—a situation that not only leads to the death of workers but makes it impossible for these workers to seek justice. The system is rigged, and the bodies pile up, quietly and systematically.

As Steve Tombs puts it, these deaths are not random but the result of “avoidable business-generated, state-facilitated violence: social murder.” This is the reality of the so-called ‘Better Regulation’ system we live under—an economy where workers are sacrificed for profits, and the bodies of the dead are quietly swept under the rug of official silence.

Image Source: The Open University Social murder: The realities of ‘better regulation’ in contemporary Britain.

This highlights the deeper issue—what we’re witnessing is a war on the working class, fought not with guns, but with spreadsheets, deregulation, and silence. We cannot allow ourselves to be numb to these deaths, nor should we accept that this is simply the cost of doing business. Workplace deaths are not inevitable—they are the outcome of decisions made by people in power who value profit over lives.

More Than a Memorial

International Workers’ Memorial Day is not a symbolic ritual. It is a political act. A refusal to accept that death is the price of labour. A demand for accountability. We must not allow the deaths of workers to fade into background noise.

We must mourn for the dead, yes. But just as importantly, we must fight like hell for the living, so that no more lives are needlessly lost. For when workers die, it is not just a loss to their families—it is a failure of the system. It is a failure of regulation, of oversight, and of the priorities that drive our economy. It is a failure of the state, and of the corporate and governmental structures that allow this to continue.

The fight for workers' rights is not just about better pay or conditions—it is about safety. It is about the fundamental right to live and return home at the end of every day's work. This International Workers' Memorial Day, let us not only remember those who have died but also those who continue to be exposed to preventable harms every day. Let us demand better, and let us fight—not just for the dead, but for the living.

For those looking to learn more, advocate for change, or support efforts to prevent further workplace deaths, the following organisations offer valuable resources, guidance, and opportunities for involvement:

UK-based Resources:

- Trades Union Congress (TUC): www.tuc.org.uk

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE): www.hse.gov.uk

- ACAS (Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service): www.acas.org.uk

Global Resources:

- International Labour Organization (ILO): www.ilo.org

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA): www.osha.gov

- LabourStart: www.labourstart.org

- Global Labour University: www.global-labour-university.org

- World Health Organization (WHO) - Occupational Health: www.who.int/occupational_health

Resources for Advocacy and Action:

- Campaign Against Climate Change Website: www.campaigncc.org

- National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (National COSH): www.coshnetwork.org

- The Workers' Memorial Day Foundation: www.workersmemorialday.org

- Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH): www.iosh.com

Sharon Hartles, Member of the Harm and Evidence Research Collaborative, The Open University. Member of the British Society of Criminology. Affiliated with the Risky Hormones research project (an international collaboration in partnership with patient groups).