You are here

The Legacy of Diethylstilbestrol (DES): A Systemic Failure and the Fight for Justice

On 11th April 2025, ITV News reported that more than 150 people had come forward following its investigation into a controversial anti-miscarriage drug: Diethylstilbestrol (DES). As a result of this investigation, pressure is mounting on the Department of Health to intervene.

Layla Moran MP, Chair of the Health and Social Care Committee, issued a clear call for government action: “...whether it’s infected blood, thalidomide, or whatever it is—it would strike me that this would fit those criteria... the government should be looking at how they can start that process.”

The government’s response was swift. Health Minister Stephen Kinnock acknowledged the issue’s long-standing nature and the need for action and further investigation, stating:

“The Secretary of State has asked officials to report back... we will be bringing forward... proposals on how we might investigate it further. We will need to work on it rapidly... this has been an issue for a very long time.”

But does the government’s response go far enough? With no formal apology issued, no public inquiry launched, and no compensation scheme in place, many are questioning whether the response truly reflects the scale of harm caused by DES.

What Is DES?

Image: Created using Canva's Dream Lab by Sharon Hartles on Canva, using assets from Canva’s Text-to-Image feature.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) was developed in 1938—a synthetic estrogen hailed as a “wonder drug.” Prescribed to pregnant women to prevent miscarriage and later used to dry up breast milk, it was marketed as safe and effective despite a lack of scientific rigor and deeply flawed research practices. By the 1950s and ‘60s, DES was given to millions of women across the US, UK (an estimated 300,000), Australia, Canada, and beyond—under various brand names like Estrosyn, Domestrol, and desPLEX.

The drug was often administered in high doses during the first trimester, with no consideration for long-term effects. It was promoted and prescribed routinely, even prophylactically (to prevent disease or infection). Pharmaceutical companies like Eli Lilly, Squibb, and Merck prioritised profits over the safety of the people they were supposed to serve.

As Lucinda Finley aptly put it: “The exclusive focus of the pharmaceutical industry on what DES might do for women, instead of also on what it might do to women, demonstrates their greater concern for controlling the female reproductive system for profit than for the ultimate health and safety of women.”

The Personal Cost: Michelle Cowen’s Battle for Justice

Michelle Cowen, a lifelong advocate for those affected by DES, has spent over 30 years seeking answers and accountability. Now in her seventies, she remains committed to highlighting the failures that left so many without information or support.

Reflecting on her experience as someone exposed to DES in utero, she described it as one of “pure negligence and pure lack of regulation” on the part of the government. She believes she was effectively poisoned by the drug her mother was prescribed during pregnancy. “It caused years of infertility, which was very upsetting after you get married, and it was very sad; you didn’t quite know what to do and how to address it,” she shared during an interview with ITV News.

Her story echoes the growing number of first-hand accounts from other UK women exposed to DES. Many have bravely shared their own experiences of harm, loss, and neglect. Their words stand as a stark reminder of the human cost of this systemic failure - both corporate and institutional.

The Ripple Effect Across Generations

The impact of DES is not confined to those who were directly exposed; it spans multiple generations. The children and grandchildren of women who took DES continue to face the consequences, a testament to the long-lasting and generational nature of this harm. The societal structures that allowed DES to stay on the market for so long have created ripple effects that continue to affect families, compounding the devastation across generations.

- Mothers who took DES: Experienced a 30% increased risk of breast cancer, along with ongoing psychological trauma and numerous medical complications.

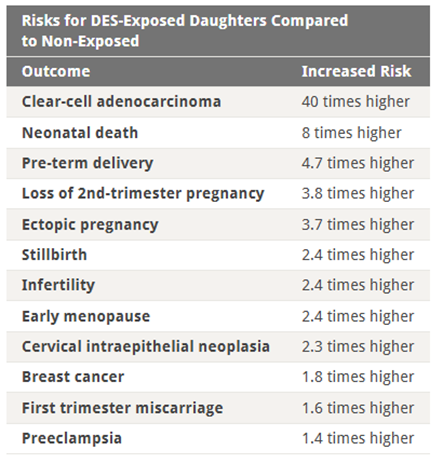

- DES daughters: Exposed in utero, many developed clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA), a rare form of vaginal cancer, as well as reproductive tract abnormalities, infertility, and autoimmune conditions.

Image: Table from the NIH study Adverse Health Outcomes in Women Exposed In Utero to Diethylstilbestrol (DES), showing increased risks for DES-exposed daughters compared to non-exposed. Image credit: National Institutes of Health (NIH), via U.S. National Library of Medicine, public domain.

- DES sons: Often suffered from genital abnormalities, infertility, and an increased risk of testicular cancer.

- DES grandchildren: Emerging evidence suggests that even the grandchildren of those exposed to DES may face reproductive and developmental challenges due to epigenetic changes passed down through the generations.

These effects represent only a fraction of the harm caused. The full scope of the legacy of DES is still unfolding, as ongoing research uncovers previously unrecognised health consequences and generational impacts, offering a deeper understanding of its far-reaching consequences.

From Science to Silence: How Truth Was Buried

Evidence emerged as early as the 1950s that DES was harmful, warnings about its efficacy and safety were ignored by the very institutions that should have protected the public. It was not until the landmark 1971 New England Journal of Medicine study linking prenatal DES exposure to clearcell adenocarcinoma, the connection between DES and cancer, reproductive harm, and lifelong health problems has been undisputed.

Yet, even in the face of undisputed evidence, the UK response remained sluggish. DES continued to be widely prescribed and promoted, even as the dangers became clearer. The drug wasn’t officially withdrawn from the market until 1978, and some women continued to be prescribed it into the 1980s. The UK’s lack of action, particularly in contrast to the more proactive responses seen in countries like the US, reflects a deeper, institutional failure. There was no formal recall, no public inquiry, and no warning issued to the women who had been prescribed DES.

False Promises and Corporate Deception

DES was marketed on a foundation of questionable claims. Pharmaceutical companies promoted it as a wonder drug that could prevent miscarriage, premature birth, and weak babies—despite a complete lack of clinical evidence. In the U.S., advertising was audacious: “Yes! desPLEX to prevent abortion, miscarriage, and premature labor… bigger and stronger babies, too. No gastric or other side effects… in either high or low dosage.”

Image: A 1957 advertisement for the drug DES, originally published in prominent medical journals aimed at doctors. Image credit: DES Daughter, "desPLEX", via Flickr, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The widespread use of the drug was fuelled by aggressive marketing, flawed science, and inadequate regulation. At the time, no legal requirement existed to prove a drug’s safety or effectiveness before it reached patients. DES was pushed into widespread use based on theoretical assumptions and uncontrolled studies. The UK's first drug safety authority—the Committee on Safety of Drugs—wasn’t even formed until 1963. By then, DES had already been widely prescribed for over two decades.

A System Built to Protect Profit, Not People

This lack of regulation created a vacuum in which pharmaceutical giants operated virtually unchecked. Their influence extended deep into medical practice, with companies exploiting the trust of doctors and patients alike. With no obligation to submit data or undergo clinical scrutiny, DES’s risks were downplayed, denied, or simply ignored.

The institutions designed to protect public health instead shielded corporate interests. In the UK, no regulation became its own de facto policy, where the absence of oversight served industry interests. DES didn’t just fail—it revealed how the system itself was built to fail those it claimed to serve.

A Broken System, Still Breaking Lives

Today, that systemic failure continues to haunt those affected. Crucial medical records from the time DES was routinely prescribed have been destroyed, or lost, leaving many without documentation to confirm their exposure. As ITV News recently uncovered, individuals who suspect they were exposed are now demanding access to specialist screening for DES-related cancers and reproductive complications.

The state-corporate harm inflicted is not just physical; it’s structural. The silence that followed DES wasn’t accidental—it was engineered by a state-corporate nexus more invested in protecting its image than its people. For those still living with the fallout, the legacy of DES is one of betrayal, not by accident, but by design.

Time to Act

As the lived experiences of those affected come to light and legal action potentially looms, the government’s response—while welcomed—must go beyond internal reviews. Health Minister Stephen Kinnock’s pledge to "work on it rapidly" should be followed by concrete action. This requires more than an internal investigation.

Government accountability must extend to a formal public inquiry, the creation of a national compensation fund, and the issuing of, a long-overdue, official apology to those affected.

The legacy of DES is not a simple mistake—it is a profound failure marked by institutional neglect and buried truths. If the government is truly committed to justice, it must listen—not only to officials and experts but also to the survivors whose lives have been irrevocably altered by the silence surrounding this injustice.

In the first instance, the calls for a thorough investigation must be acted upon—but an investigation alone is not enough. Delays and dismissals are no longer acceptable. History has shown that accountability only comes when denial is replaced by truth —and when survivors not only receive recognition but redress.

Resources and Support for Those Affected by DES

If you or someone you know has been affected by DES exposure, support is available. Below are some resources that may help:

- To learn more about the potential health impacts of DES, including cancer risks, there are several public health resources that provide up-to-date guidance.

National Cancer Institute - DES Fact Sheet - The UK government offers information on cervical screening, which may be especially relevant to those with a history of DES exposure.

UK Government Guidance on Cervical Screening - A legal support campaign has been launched by a UK-based firm to assist those seeking justice—offering advice, representation, and a space to share your story.

Legal Support Campaign for DES Affected Individuals - The NHS provides clear, accessible information on both cervical and breast cancer, including symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options.

Information on Cervical Cancer from the NHS

Information on Breast Cancer from the NHS - If you're concerned about your health or experiencing symptoms, reach out to your GP. NHS 111 is also available online or by phone for urgent medical guidance.

NHS 111 for Immediate Medical Assistance

No one should have to face the legacy of DES alone. Support, recognition, and solidarity are crucial as we push for truth, justice, accountability and change.

Sharon Hartles, Member of the Harm and Evidence Research Collaborative, The Open University. Member of the British Society of Criminology. Affiliated with the Risky Hormones research project (an international collaboration in partnership with patient groups).