You are here

Lies, Damned Lies and Statistics… and Scottish Independence Referendum ‘Facts’

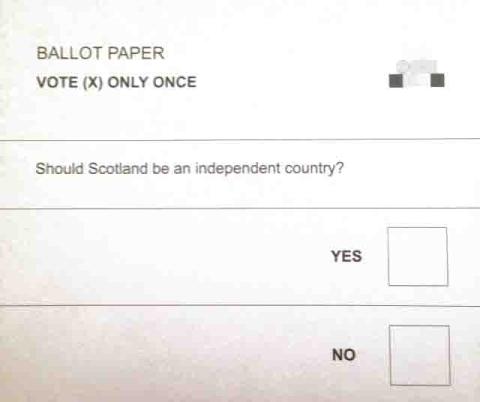

On the 15th October 2012 an agreement was reached to hold a single question referendum on the future of Scotland. This referendum was held on the 18th September 2014 and the people of Scotland were asked: Should Scotland be an independent country? Of the people who voted, 45% voted yes and 55% voted no.

While the independence debate has been developing for decades, during the two-year period leading up to the referendum, different forms of evidence were mobilised to advance the respective positions for and against Scottish independence. Inevitably, within the respective ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ camps there were different perspectives and shades of opinion, including different (positive and negative) visions of what an independent Scotland would or should look like.

Many ‘No’ supporters were in favour of additional devolved powers for Scotland – of varying degrees. This became a big issue in the final week of the campaign and has been to the fore in the debates following the referendum. This is reflected in notions of ‘devo-plus’ (a few more powers for Scotland) and ‘devo-max’ (maximum powers devolved but Scotland remains within the UK). One of the fears of those who voted ‘no’ was that Scotland would not be able to survive in the longer term on its own and would be severely diminished outside the UK.

To make this case, the ‘No’ camp deployed a range of experts who were thought to command respect and who would help to inform opinion. One of the most controversial areas of the entire debate revolved around the ability of an independent Scotland to fund, from its own resources, the far-reaching and expensive programmes of social welfare and childcare that were seen as being central to the creation of a new kind of Scottish society. Oil revenues were highlighted by both sides as supporting their respective positions: the ‘Yes’ campaign argued that new technologies and newly found reserves in what would become Scottish territorial waters would be able to fund all of the comprehensive spending plans of any incoming independent Scottish government. These claims were disputed by the ‘No’ camp, which relied on their experts to question the longevity and sustainability of the oil reserves. The ongoing debate focused on issues of measurements, definitions, different methods of accounting for oil stocks and revenues. Each and every piece of evidence presented was contested or fought over in some way or another.

The nature of evidence

It is clear that, throughout the Independence debate, particular kinds and forms of evidence played a role in shaping the debate and persuading people to vote in a particular way. For example, opinion polls, which could be argued to be one of the most influential forms of evidence in the debate, played a major role. The YouGov polls clearly showed that up until the final weeks prior to the referendum there was a majority in favour of No (60%/40%). However, at the start of September this narrowed to 51% No and 49% Yes and then, on the 7th September, a poll showed a narrow lead for Yes. This apparent surge in support for the ‘Yes’ campaign sparked a Westminster panic and all three major UK party leaders, together with other ‘No’ campaigners such as Gordon Brown, campaigned vociferously and promised Scotland ‘devo-max’ style powers if a ‘No’ vote was secured. It could be argued that these promises (soon to be broken after the vote) resulted in the final ‘no’ vote for independence. Some people who voted ‘no’ wanted to see change in Scotland, but did not want to be independent, and the Westminster government promises of ‘devo-max’ powers may have offered the best solution to some.

Of particular interest is an examination of what counted as evidence and how it was constructed and represented during the debate. For example, there was a great deal of discussion surrounding identity and nationality among different groups in Scotland (see Nicola McEwen for a discussion of some of the issues). This was primarily in a bid, prior to the vote, to establish how particular groups would vote and where to target campaigns. Between 2012 and 2014 What Scotland Thinks conducted a number of polls on identity. Questions included ‘Where on this scale would you place your identity?’, ‘Would you feel most proud describing yourself to someone from overseas as British or Scottish?’, ‘Do you agree or disagree that if Scotland becomes independent, I’ll feel British due to geography, history and culture?’ and ‘Do you agree or disagree: If Scotland becomes independent, I will never think of the English as being foreign’. The wording of these questions, the conflation of complex issues and the differing response options used, all served to produce different responses to quite similar identity related issues. Each of these individual questions could be used to produce a very different and inaccurate construction of Scottish identity.

Furthermore, polling data was often presented by both sides as ‘clear’, only showing data for those with clear yes or no opinions and omitting those that were unsure which way to vote. Other examples of the different ways in which evidence can be used to reflect particular interests were observed on a number of levels throughout the campaign. Experts were seen to disagree on the economy and currency issues, while newspapers and other sections of the media often provided emotive, often sensationalised opinion – as did some politicians – not least from the ‘No’ side of the debate. There were very few ‘facts’ – and even fewer uncontested facts – during the two-year debate and, where there were, they were aligned so much with particular political affiliations that it was almost impossible to view them as ‘facts’. This was seen most starkly in the discussions on oil reserves in Scotland. Issues concerning the number of barrels, the volatility of oil prices, annual tax revenue and future oil fields were contested by politicians and industry experts. For example, Sir Ian Wood, in a Guardian article accused the SNP of exaggerating the figures by up to £2bn a year. However, Professor Sir Donald Mackay argued that the UK government had underestimated the value of oil. This is an excellent example of how the use of evidence in a political debate always reflects particular interests and cannot – especially in such a highly charged and highly politicised context – be regarded as in any way ‘neutral’.

This was also evident in the way in which the print media reported the debate. While The Guardian did contain some pro-independence articles, the first and only UK newspaper to openly support the independence campaign was The Herald. Most of the print media was pro-union and there were many scaremongering headlines in the press, particularly around currency issues and the economy. Importantly, research has shown that repeated exposure to media messages can impact on public opinion and social change. The authors of that research suggest that repeated exposure to negative messages about the uncertainty of the economy and currency issues may have limited the impact of the ‘Yes’ campaign. Furthermore, it could be argued that this repeated exposure to negative messages and scaremongering about Scotland may also have shaped the opinion and attitudes of the people in England, both toward the referendum itself and towards the issues surrounding independence and self-governance.

How did people make a decision?

Despite the obvious issues surrounding the biased representation of evidence, the people of Scotland still had to make a decision – but it was impossible to know what evidence to trust. In this context of uncertainty, there was a massive increase in the popularity and use of different social media sites and they became one of the most important sources of evidence in the debate, especially for the proponents of Scottish Independence and among the younger age groups. The use of Facebook and Twitter in particular played a significant part in helping to politically energise people who had previously never thought of themselves as being ‘political’. Data from Facebook reported that there were over 10 million posts about Scottish independence in the weeks before the referendum, with 85% of those originating in Scotland. During this process, almost everyone became an ‘expert’. Links were shared, documents were discussed, and people debated the benefits and disadvantages of becoming an independent nation. The issues were complex, opinions were diverse, and at times it was almost impossible to see the huge diversity and complexity that was hidden behind the respective positions for or against independence for Scotland.

Psychologically, this process of debating the evidence highlighted many aspects of group processing that have been documented widely in the social psychological literature. In particular, many aspects of Tajfel’s (1979) Social Identity Theory were evident through Facebook posts. This theory proposes that belonging to a group gives us a sense of identity and of belonging, which gives purpose and self-esteem. Once groups are established through a process of debating, finding common goals and conforming to group ‘norms’ , an identity is formed which can then lead to division: a ‘them’ and ‘us’ process of social categorisation which can be seen in almost every group (for example, and perhaps especially, amongst rival football supporters).

This classic social psychological process of group formation actually helped to promote debate and discussion. When people had finally decided, some of them placed ‘yes’ or ‘no’ stickers on their profile photographs. This was partly to identify themselves as a member of either group, but it was sometimes there to tell people that they’d made a decision and no further discussion was needed. While this obviously created a ‘divide’, there had to be division. The nature of the yes/no vote insisted on it! Importantly, the debate was healthy, lively and informative. Many people felt that this was the most important vote in their lifetime and passions were high. Unfortunately, many sections of the media picked up on this perceived divide and used sensationalist headlines to propagate the myth of division. For instance, The Independent ran the headline, Scottish Independence Referendum: A nation divided against itself , while hugely emotive words such as ‘crazy’ and ‘anarchic’ were used prior to the vote to ridicule some of the claims made by the ‘Yes’ campaign. Similarly, words such as ‘reconciliation’ were used after the referendum result was announced. No such reconciliation was needed. As Alex Massie writes ‘If Scotland’s independence campaign is notable for anything it is unusual for being remarkably civilised’.

From a sociological viewpoint, the referendum was also hugely important. It is clear that the movement for Scottish Independence was a social movement in the classic sociological meaning of the term. This was a movement that transcended national/ist issues alone to encompass campaigns against UK government austerity, poverty, corporate greed, nuclear weapons and wars. What is clear from this referendum is that the people of Scotland took this vote seriously. They searched for facts, for guidance, for evidence. In the end, they became their own experts.

Gerry Mooney and Hayley Ness, International Centre for Comparative Criminological Research, The Open University