Merseyside Football’s Earliest Patrons and the Slave Trade Connection

Dr David Kennedy & Dr Peter Kennedy

Introduction

Everton fans with an interest in the club’s history will be well aware of Everton’s Founding Fathers. Men like Will Cuff, George Mahon and James Clement Baxter played a particularly influential role in the early development of the club. Those men are fully deserving of their honoured status and of the interest Evertonians pay them. By contrast, Everton’s first patrons - a group of men invited by the club committee to endorse Everton FC in the very earliest years of the club - remain an unheralded cohort and all but ignored by historians of Everton. This, perhaps, is understandable given that they played nothing like a central role in Everton’s development as an organisation. However, knowledge of who the patrons were can offer us another window through which to view the club’s initial ambitions. It can also help place the fledgling club within the context of the life of the city of Liverpool during the early 1880s. There is a distinct maritime flavour to this group and, as we shall see, it is a connection that touches upon a dark chapter of the city’s past.

Who were the Everton patrons?

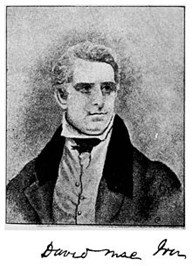

They were a collection of merchants, industrialists, brewers, politicians and officers of the local state. Scotsmen Robert Galloway and David MacIver were shipping merchants of some note; the latter especially so as co-owner of the world-famous Cunard line. The presence of Robert Blezard, a brewery owner, and Edward Whitley, a scion of the famous brewing family, reminds us of the importance of this industry to the early development of many football clubs in England – Everton and Liverpool included. Reinforcing the commercial profile of the patrons was director of the Liverpool United Gas Company, James Barkeley-Smith. In fact, only the MP for Liverpool, the Earl of Harrowby, and Liverpool city coroner, Clarke Aspinall, were not businessmen.

The 3rd Earl of Harrowby, Dudley Stuart Ryder, one of Everton’s earliest patrons

They were men of great local influence, and some of them also had a national profile. It would seem to have been an audacious move by the Everton Committee then to invite such luminaries to endorse, what was at the time, a minor sports organisation. Liverpool’s commercial class, however, were adroit at connecting with local society via cultural patronage as a means of projecting their status and promoting their civic ambitions. They were to the fore in patronizing educational establishments, the arts and sports associations. It is unsurprising, therefore, that a local and increasingly popular football club, with an obvious potential for mass support, would find favour amongst this class of people.

Unfortunately, we don’t know the full extent to which the patrons involved themselves with Everton FC. In this respect, we suffer due to the absence of surviving club documents at this very early stage of its development, and the sparse coverage of football in the Liverpool press at the time makes the task of determining the degree of their influence no easier. On the small number of occasions that the Everton FC hierarchy are mentioned in the local press after its formation as a district team and the final year of its association with the patrons - 1879 to 1884 – there is no mention of any of the patron’s names. It is questionable, therefore, whether they played any formal role in the club. We might reasonably surmise, though, that there may have been a calculation by the club committee to exploit the patrons’ presence in order to impress on those further afield of their status as the ascendant and representative club of the city of Liverpool. This would have been an important consideration for a club considered to be the premier club in the city of Liverpool but who sought to make the step up to being considered one of Lancashire’s elite football clubs.

The Maritime Connection

Pivoting away from the nature of the relationship between the patrons and Everton FC, it should be mentioned that – this being Liverpool - there was a strong maritime link to their presence. The Cunard connection to the club via David MacIver perhaps best exemplifies that relationship to the port economy, and the patronage of Robert Galloway, whose shipping company Moran, Galloway Co. plied its trade with South America, underlines this link. Other patrons too had their maritime connections. In the early nineteenth century, Clarke Aspinall’s family were one of the foremost ship owners in Liverpool, with trading interests on both sides of the Atlantic. The Earl of Harrowby, like his father Lord Sandon before him, was a Liverpool MP closely associated to the cause of the Liverpool Brazilian Association, whose members traded to the South American country and were an especially powerful lobby in the city of Liverpool. James Barkeley Smith, as well as being a gas company owner, was a long-standing chairman of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board and a committee member of the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce, a body dominated by the concerns of the port economy and boosting the trading interests of Liverpool’s maritime merchants.

Unfortunately, and as we know, Liverpool’s maritime history is not without its dark chapter, and there are direct and indirect associations between some of these men and the exploitation of coerced forms of labour. This might sound anomalous as there is a yawning time gap between the emancipation of slaves in the 1830s and the formation of Everton FC in the last couple of decades of the nineteenth century. However, the period in between saw the continuation of slavery and other unfree forms of labour outside of British colonial control. This is obviously a very sensitive issue, and Liverpool’s reckoning with its past is an ongoing process, so any evidence of the patrons’ association with such exploitation should be examined.

Robert Galloway was a merchant of note in the South American trade, and more particularly with Peru, where the principal cargo of Moran, Galloway and co. was ‘guano’. Guano is calcified bird manure and was used as a natural fertilizer. Guano was in great demand from European countries for agricultural development prior to the emergence of chemical fertilizer. Though slavery was outlawed in British colonies in 1833 it was still, until 1854, an economic system found in Peru, and persisted thereafter surreptitiously. Before abolition in 1854 Peruvian guano mining was carried out exclusively by African slaves. Subsequently it was mined by kidnapped (‘blackbirded’) Pacific Islanders, or else by Chinese ‘coolie’ labour - 100,000 of whom were transported from China to Peru between 1849 and 1874. Galloway, therefore, profited from numerous forms of coerced, unfree labour: slaves and indentured servants alike. The conditions of the work were disastrous: lung damage from breathing in guano dust was almost guaranteed – a practical death sentence. Often workers were buried alive by falling piles of guano, and insurrections were brutally put down, with floggings commonplace.

.jpg)

Chinese ‘coolie’ labourers guano mining, Peru 1865

A controversial figure, in 1874 Galloway was accused of using one of his company ships, the Tempest, to run arms to Peru in aid of the dictator in waiting, Nicolas Pierola, who used the supplied weapons to launch a coup on the Peruvian Government. Questions were asked in the British Parliament concerning the incident (described as an act of ‘piracy’ by the MP for Glasgow, Dr Charles Cameron) and of Galloway’s part in it (Hansard 21 March 1876). He was accused of seeking the overthrow of a foreign government in order to secure a monopoly on the Peruvian guano trade from a newly-installed regime, led by Pierola. This was a charge denied by Galloway, but the incident forced his resignation from the committee of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board. Galloway later became a Conservative city councillor for Everton in 1880 and his association with the popular football club of the district would no doubt have been designed to boost his popularity.

Portrait of David MacIver (1896). Co-Founder of the Cunard Line

David MacIver was the driving force behind D&C MacIver Shipping Co. and the Cunard shipping line – a commercial colossus in Liverpool’s maritime power. But evidence of the behavior of MacIver and Cunard during the American Civil War period doesn’t look especially enlightened for this particular Everton patron. Documents from the Liverpool-based American Chamber of Commerce during the conflict underline that MacIver was a pronounced supporter of the southern states’ cause (Powell, 2018). Certainly, incidents such as the use of Cunard personnel crewing Confederate ships built at Birkenhead’s Cammell Laird ship yard during the conflict and MacIver’s bringing of Liverpool city council Conservative leader, Sir William Forwood (a man who made his fortune running ships through the Union navy’s blockade in order to supply the Confederacy with arms), onto the Cunard board of directors give a clear indication as to the MacIver and Cunard attitude toward the southern pro-slavery states.

Cunard’s core business was primarily the carriage of passengers and mail from English ports to New York and Boston. And the sporadic reports of the company’s attitude to the carriage of black passengers hint at a discriminatory policy. In one infamous case the African-American abolitionist orator and politician, Frederick Douglass – described as the most famous black man in the world during the nineteenth century – was denied the right of first-class passage on board the Cunard passenger ship Cambria for its journey from Liverpool to Boston in April 1847. Apparently deferring to the wishes of American passengers, Cunard rescinded Douglass’s first-class ticket, with the explanation that the sale of one to him was the mistake of a London-based selling agent. Douglass was given a steerage ticket, and instructed to take his meals alone in his allotted cabin and to stay out of the saloon areas of the Cambria – effectively exercising a partition of Douglass away from other (white) passengers.

The incident - via the English press - became a scandal and a major source of embarrassment for Cunard. Nevertheless, the MacIvers stuck to their guns on the decision to separate Douglass from the other passengers, claiming that on the first leg of his journey from the United States to England the African-American orator had provoked a “serious disturbance” amongst other, predominantly American, passengers by entering the saloon – an event alternatively characterised by Douglass’s supporters as a mob looking to throw him overboard, which was only avoided by the intercession of the Cambria captain. This would not be the last time Cunard’s reputation was called into question over the subject of its concession to American racist hostility toward African-Americans. In the House of Lords the British peer Lord Brougham drew the attention of the chamber to a journey he had on board a Cunard liner where he had witnessed racial discrimination. ‘Debate in the House of Lords’ Douglass’ Monthly, September 1860 .

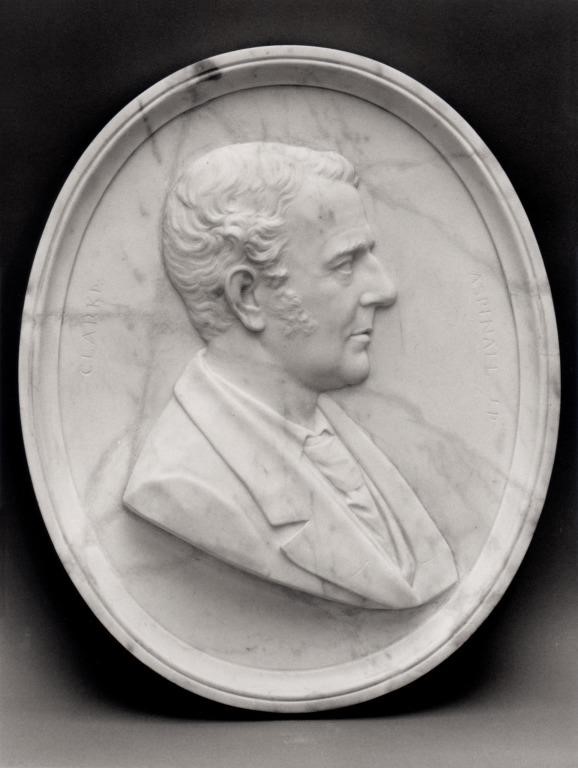

Everton patron Clarke Aspinall, the Liverpool city coroner did not, it is important to stress, own slaves or directly profit from their labour. But the wealth of the Aspinall family from which he benefited came decidedly from that source. This is point acknowledged by one of the city of Liverpool’s most prestigious institutions. A portrait of Clarke can be found in Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery with the following inscription: ‘This artwork has been identified as having links to a person connected with trans-Atlantic slavery.’ Clarke’s mother’s South Carolina-based side of the family-owned substantial sugar plantations in Jamaica. However, it was on his father’s side of the family that notoriety was gained. His grandfather, John Bridge Aspinall, a founding member of the African Merchants Company, created in 1750 by royal charter to aid the expansion of Liverpool’s Atlantic trade, profited greatly from the 113 slave voyages his shipping company made between 1785 to 1807, transporting upward of 68,000 enslaved Africans from the Bight of Biafra in Nigeria to the Americas.

The Aspinall name became infamous though due to the part played by John’s brother, James Aspinall, in the most horrendous act of barbarity in the centuries-long period of the Atlantic slave trade: the Zong Massacre of 1781. James Aspinall was the co-owner of the slave ship ‘Zong’. In November 1781, over 400 enslaved people – many more men, women and children than was allowed for transportation on that particular vessel - were loaded on board at Ghana for the voyage to Jamaica. During the Atlantic crossing the ship ran low on drinking water due to a navigational error. With a deterioration in the health of their ‘cargo’, one hundred and thirty-one of the enslaved were thrown overboard and drowned by the crew.

The long-term significance of the Zong disaster was that the events on board that ship and the legal case and judgement in its aftermath played a crucial part in the campaign for the abolition of trade in slaves, which was eventually achieved in 1807.

Clarke Aspinall was a learned man and would have been fully aware of the central role his family had played in the history of Atlantic slavery, and the misery and degradation it caused. It is perhaps instructive that his biographer, who touches extensively on the Aspinall family’s slave trade history, makes no reference to his subject’s views on the matter. Clarke, in fact, took a great deal of pride in his family - choosing to celebrate his slave owning grandfather by offering a full-size portrait of his merchant forebear to the Town Hall where the slave trader once resided as Mayor of Liverpool. The wealth of the Aspinall family - bolstered post-slave trade by their diversification into palm oil trading (an industry using many forms of unfree and coerced labour in West Africa) - would have greatly shaped the life of Clarke, handing him every opportunity he had in life.

Liverpool City Coroner, Clarke Aspinall

Conclusions

By the standards of the day, the football patrons were considered as completely credible members of the local business and political elite. That Everton’s committee would seize on the opportunity to invite such men to take up a role in the district’s football club was, at the time, an unsurprising – and unproblematic - development. Compare and contrast this though to the attitude of present-day Everton FC. Mindful of the sensitivity surrounding the issue of slavery in a city at the heart of the Atlantic slave trade, the club have indicated that its new stadium, built on a dock named after a Brazilian slave trade merchant, John Bramley-Moore, will have a lasting memorial to the victims of slavery. ‘What happened across Liverpool in terms of slavery should not be airbrushed out of the city’, commented an Everton spokesperson in August 2021. ‘It is a huge part of our history and we have to face up to that’. The official history of the club however does not address their earliest patrons or their maritime links. This should be something the club addresses in the future given the commitment to not ‘airbrush’ out the legacy of slavery.

.jpg)

John Houlding: Everton President (1881-1892) and founder/chairman of Liverpool FC

It should also be remembered that the patrons’ story is not exclusive to Everton FC. Given their shared heritage this story is also linked to Liverpool FC by virtue of their shared heritage to the original pre club-company organization that split in 1892 into two organizations. Liverpool FC owner and founder, John Houlding – a man fundamental to the creation of Liverpool FC after his dismissal from Everton in 1892 – was the prime mover in attracting the above-named patrons to Everton FC. And Houlding, incidentally, is someone who had his own indirect associations to the slave trade, being connected to the Milliken-Napier family by marriage, who owned extensive sugar plantations on the Caribbean island of St Kitts. We are informed by the record books from ‘The Old Glasgow Club’ that sporadic slave revolts on their plantations were ‘harshly dealt with, usually involving hanging or burning.’

In a general sense, football is an area of study barely explored in discussions about the era of slavery. This is all the more surprising given what we now know to have been the nature of slave ownership in Britain. The records of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery demonstrate that there were 46,000 slave owners in Britain in 1834 who claimed for compensation from a fund set up to remunerate their loss of income from slave emancipation. Amongst these were, of course, large slave owners with huge plantations and who built up massive fortunes. But there were larger numbers of middle-class slave owners who owned a few slaves – the class of people who invested in and governed Victorian sports organisations. And slave ownership was far from being just prevalent in ports cities like Bristol, London, Liverpool and Glasgow – traditionally associated with slave trade economic activity – rather, slave owners came from across the country, ‘from Cornwall to the Orkneys’. Ownership records demonstrate the flow of slave capital to subsequent generations of slave owners to be substantial. As this study demonstrates, despite the time gap between the emancipation of slaves in the 1830s and the formation of most of our football clubs in the last three decades of the nineteenth century, there are links and associations to be made between football and individuals who directly or indirectly benefitted from slavery and the exploitation of other forms of unfree labour.