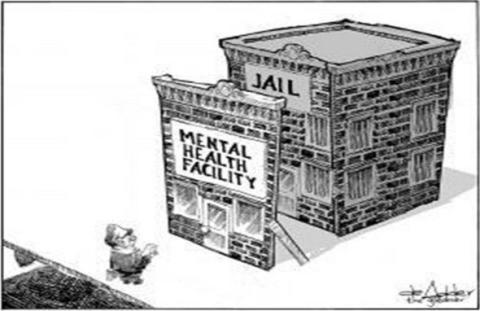

Prison is not a safe place for people with mental health problems

Prison as a warehouse for mental health problems – Source: Pinterest.com

In extreme circumstances or environments, psychological wellbeing can be precarious and effectively ‘under siege’ even for those with robust internal coping strategies. Prisons are such environments. They are places that can induce extreme stress and distress. For those living in the extreme environment of the prison, the line between mental well-being and diagnosable or enduring mental illness can be blurred. There are three distinct, yet overlapping, populations to consider when taking account of mental health within prisons:

- Those who are committed to prison with a pre-existing (either diagnosed or not) mental health condition. Prisons are places that tend to confine a disproportionate number of people with mental health problems. Mental health problems, for this population, are imported into prison with them.

- Those who are committed to prison without a diagnosed pre-existing mental health problem but have a latent mental illness that can be triggered in the stressful or traumatic environment of the prison.

- Those who are committed to prison without a pre-existing mental health problem and no history of mental health problems, but during the course of a prison sentence develop mental ill-health or experience extreme deterioration of psychological well-being.

The prison environment

Prisons are designed as ‘anti-social’ places. They de-stimulate, create barriers to positive human interaction and deliberately promote conditions that exacerbate feelings of alienation, anxiety and despair. This is part of their stated purpose as places of punishment. Although the research literature on the enduring social and psychological impact of imprisonment is complex and, in some ways, inconclusive, it is well understood that the prolonged passivity and antisocial nature of prison life leads to individual and social isolation and, as a result, the prison place can present a serious danger to the mental health of those confined and those who work within its walls. Prison officer stress is a relatively well-researched problem in multiple jurisdictions and attests to the inherent damage of the prison environment.

Numerous aspects of the daily prison regime are harmful: separation from social life and from family and loved ones; over-crowding; loss of autonomy; frustrations in dealing with the minutiae of everyday life; limited mental or physical stimulation; negative relationships rooted in fear, anxiety and mistrust; physical, emotional, sexual or financial exploitation; inadequate ventilation, nutrition and care and a general culture of stigmatisation and distrust. Sitting alongside these harms are the ever-present structured pains of confinement that characterise the loss of one’s liberty and, for many, the uncertainty of what they will face upon release.

The suffering and isolation of prison – Source: ferloo.com

Greater vigilance is needed amongst psychological and penal experts to avoid over-applying ideas about enduring psychological difficulties located within individuals when those individuals are living in the extreme environment of the prison. Prisoners can be individually “pathologised” and, as a result, there is a masking of deeply entrenched iatrogenic harms and institutionally-structured violence that characterises the daily workings of the prison. We must remain observant of the way in which the label of ‘mental ill-health’ can be deployed as a means to classify, manage and disempower people within the existing perimeters of legal and medical authorities rather than reflecting the interests or needs of the individual labelled as such. In recent decades there has been an increasing readiness to recognise ‘pathological’ traits in prisoners who may formerly have been regarded as ‘normal’.

At the same time mental health may significantly deteriorate or only start to manifest itself as a problem once a person is committed to prison. Mental health problems and confinement may, in this sense, go hand in hand. Prisoners in prison health care centres sometimes spend only 3.5 hours a day unlocked rather than the recommended 12 hours a day. Prisoners have also raised concerns that not all staff understand their problems and that they do not have much time with highly trained medical staff. Prisoners with mild symptoms are often dumped together with much more problematic cases. The result of this practice is that many prisoners with complex needs are left with too little or no support. Evidence from a range of studies which have consulted prisoners with mental health problems have found that what prisoners need are ‘someone to talk to’; therapy and advice about medication; ‘something meaningful to do’; support from staff, family and other prisoners; help when facing a ‘crisis’ and support with future planning. Such needs, however, are rarely met inside prisons.

The inappropriateness of prison for people with mental health difficulties

When understood in social and historical context it is apparent that the presence of large numbers of people with mental health problems in prisons is not an aberration but an enduring and essential part of the confinement project. Their constant presence in prison indicates that imprisonment has had a clear historical mission: to identify, classify, contain or transform ‘unproductive’, ‘distasteful’ and ‘unwanted’ elements of society.

The “General Penitentiary”, Millbank, London (Opened 1816) – Source: blackcablondon.net

Prison management requires a relatively docile population if it is to discipline the able-bodied and the presence of ‘the mad’ disrupt this. The problem of mental health in prisons has never just been a result of ‘importing people’ with mental health difficulties. From the introduction of the ‘reform prisons’ in the early 1800s there is accumulating evidence of the detrimental impact on prisoner health. For example, at the special unit on mental health at HMP Birmingham from 1919 to the 1930s Dr Hamblin Smith came to the conclusion that prisons could not be an effective means of delivering psychological treatments because the punitive ethos and the deliberate structural pains of confinement were anti-therapeutic.

On numerous occasions since the nineteenth century prison authorities have claimed that not only are mental health problems largely imported but that the prison place could be a major opportunity to address them. The modern prison is often discussed as a “health promoting environment” where prisoners can expect to receive a similar level of care (in terms of health treatment, for example) as those in the community. In practice, however, this is rarely the case. Moreover, given the extreme environment of prisons the level of care within them would need to be significantly greater than that available on the outside merely to ameliorate the negative effects of the environment alone. When we then consider those who enter prisons with serious mental health difficulties, some of whom may, arguably, require the very highest levels of care available, we see that prisons are profoundly inappropriate for responding to and treating those with extreme mental health needs.

Mental health services in prison face enormous obstacles

Mental health difficulties are undesirable, disabling and potentially frightening for all involved. When such difficulties present in a prison, the staff and other prisoners often feel ill-equipped to respond appropriately. Prisons are sometimes utilised by well-meaning judges as ‘places of safety’ for people with mental health difficulties. Prison staff on the landings (e.g. officers) and healthcare professionals alike are unable to manage these sorts of difficulties. Moreover, psychologists in prisons are – in the vast majority of cases – not focused on the mental health and well-being of prisoners.

Source: National Health Service

At the same time, tangled up in the complexity of the prison environment and the baggage of chronic cynicism and risk aversion are those who have serious mental health difficulties – either that they came in with or difficulties triggered by the environment. One of the key aims of the influential 2001 policy document Changing the Outlook was to introduce Mental Health In-Reach Teams [MHRIT] into prisons. Alongside an exceptionally high average caseload for MHRIT practitioners, MHRIT’s are also shackled by prison security, the inherent harms of prison life and the contradictory ideologies of punishment and care. With an emphasis on security and highly restrictive daily routines it is very difficult for MHIRTs to meet the needs of prisoners. MHIRTs were initially established to serve people with severe mental illness [SMIs] but many teams cannot focus exclusively on those with these difficulties because they are swamped by other cases. As a result of these difficulties and the range of other complexities associated with the prisons environment, outlined above, there is a huge amount of unmet mental health need in prisons that is unlikely to be addressed through a simple reform initiative or some other ‘programme of change’.

Learning lessons for the future

The lesson we need to learn is that prisons are places which systematically undermine well-being and health – for all who enter them (both prisoners and staff) – and for people with pre-existing mental health difficulties the prison is an especially unsafe environment to send them to. When we consider mental health in prison in historical context we find that penal confinement has consistently been used as means of housing ‘unwanted’ people who have been failed by wider social policies. People with mental health problems have been ever-present in prisons, as indeed have large numbers of deaths. If we are to change this in the future there is only one policy option that can do this – a radical reduction in the prison population coupled with improved welfare provision for people in the community and public education campaigns which can promote a more caring and supportive approach to people suffering from mental health problems. Tinkering with penal policies has been tried for decades if not centuries. It is time for a bolder, evidence based approach to mental health problems in prison that acknowledges the true nature of both mental health and the demands and harms of the prison place.

We need greater commitment to listening to the wrongdoer and the democratic participation of all parties in a given conflict when deciding the best means of redress. There must be acknowledgement that psycho-medical labels and treatments can lead to an increase in harm and that people with mental health problems require detailed information about treatment options and help in developing skills, rather than being simply stigmatised as needing some ill-defined ‘treatment’. This requires consultative interventions rooted in respect, support, patience. On the ground there needs to be active engagement with service users; the development of services people actually want to use; recognition of legal rights; and real support for finding financial security, housing, jobs, and other initiatives aimed at ending social exclusion.

There are crises in mental health despite the fact that many people with such problems cope most of the time. If we are to take the mental health problems of lawbreakers seriously we need to deploy social policies that emphasise social justice and human rights. In essence we argue that state confinement is a major obstacle to the well being of those confined and largely exacerbates or even triggers mental health problems. Ultimately what is needed are creative solutions that look beyond the prison.

Deborah H. Drake and David Scott, The Open University