You are here

Rough sleepers in policy and practice: chaotic and off course, or misunderstood?

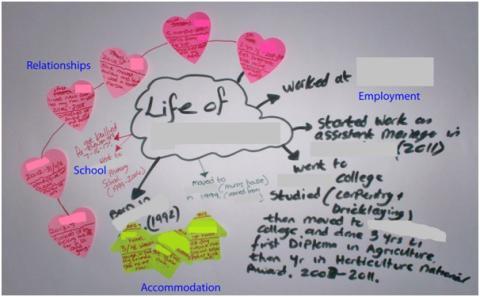

Kelvin’s life map

Since 2010 the number of people sleeping rough has increased year-on-year, according to official estimates. Historically, rough sleepers have been the subject of national government policies, which have made distinctions between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ individuals. However, more recently, government policies have also employed other terms to describe rough sleepers’ lives. Terms such as ‘chaotic’, ‘off track’, and ‘off course’ have been mobilised in policy framings of rough sleepers’ lives. These policy terms suggest a particular way of understanding the lives of rough sleepers – as disorganised, abnormal and headed in the wrong direction.

But, to what extent to these reflect the experiences and understandings of rough sleepers themselves? One way to consider this question is to explore rough sleepers’ accounts of their own lives, an approach I take here, drawing upon work undertaken for my PhD.

In that research, I spent nine months in homelessness services, talking to people who had slept rough. I also interviewed 17 people who identified as having slept rough or having had no accommodation over a period of nine months.

Rough sleepers’ stories

Within the research, life mapping was a tool employed to assist rough sleepers in creating visual and verbal accounts of their lives. Life mapping allowed rough sleepers to draw their story whilst also describing it. Below are two examples of the life maps created in the research. These maps are visual representations of rough sleepers’ lives.

As is visible from Kelvin’s life map, he did not see his life as ‘chaotic’, but rather, as orderly. Kelvin divided his account this into four main topic areas – schooling (left centre), employment (right), relationships (left) and accommodation (lower centre). Within Kelvin’s account, stories of successes and disappointments were evident. Samantha’s life map also showed order in her life.

Like Kelvin’s, Samantha’s map also shows a life which is not ‘off track’ or ‘off course’. This is visible in the line drawn between key points in her life, showing both high points and low points in her story.

Samantha’s life map

These life maps show visually the order and mixed successes of rough sleepers’ lives, which stand in contrast to the claims of ‘chaotic’ and ‘off track’ lives made in policy.

Being homeless

More generally, rough sleepers also spoke about their experiences of being homeless. Sleeping rough often required management of unusual or new situations, such as deciding where to stay and whether to engage with homelessness services. David spoke about sleeping rough in an area he knew well, and the ways in which that allowed him to deal with the risk to his safety, but also put him at risk of being seen by people he knew, saying:

“I didn’t want to leave the area ’cause I knew it so well. But I didn’t want to be seen, I was embarrassed and ashamed. I didn’t want to be seen by anyone I knew, to see me in that situation, sleeping rough. Why, I don’t know, some part of my dignity hadn’t quite died.”

To manage the difficulties that sleeping rough could bring, individuals often engaged in behaviours which might seem chaotic or unusual to others, but could be seen as rational in the context of their situation. Craig stayed in Patford, a small village over two hours walk from the nearest town. In Patford, Craig was largely unable to access the services such as food, water, and washing facilities that he would’ve been able to access in the nearest town. However, Craig spoke of his reasons for staying in Patford, stating:

“I just know it’s safe. … I can have a fire. Alright, it takes you an hour to get into town, but I’m not gonna sleep in a…doorway over here.”

Similarly, using local homelessness services could provide some facilities for rough sleepers. As Stuart noted, such services could provide vital resources, both physical and mental for rough sleepers:

“I remember coming here in the mornings, like half eight in the mornings when it opens, just like, you know, so relieved to just get in somewhere, and I’d get myself in the shower. Sometimes I’d just stand, you know, I’d stand under that hot shower for about ten minutes just standing there, you know, kind of recharging myself.”

However, homelessness services weren’t always ideal for rough sleepers, as Victor highlighted:

“I’m extremely grateful to having a roof over my head and being able to eat something. Umm, that is what I can be grateful to. I’m not going to say that the umm oh it’s a perfect place to be, it’s lovely, it’s warm, it’s this, it’s that. ‘Cause it isn’t, right. Umm, it’s horrible. It can actually get you quite down”

Planning for the Future

In addition to their accounts of homelessness, rough sleepers also spoke about their plans for the future. In contrast to policy views that saw their lives as ‘off course’ or lacking in order and long-term planning, rough sleepers spoke about the risks of making long-term plans. For many, their situation of homelessness made the future hard to plan, as was the case for Laura:

“I’m not so sure on the future. The future’s uncertain and I hate the feeling of not knowing. If I knew what was going to happen I could plan ahead, get ready for it. And my life at the moment has been for many years, it’s a waiting game.”

Jane also spoke about the dangers of making long-term plans, suggesting that it was more suitable to make short-term plans whilst homeless, as circumstances can change these plans with little or no warning:

“It’s a case of day by day now. That’s literally all it is, is day by day. No-one can predict the future. No-one whatsoever. You can try but something’ll come along and completely pull that all apart within seconds so it’s day by day at the moment.”

As Jane’s and Laura’s accounts both show, making long-term plans when experiencing homelessness can be difficult, due to the possibility of circumstances changing without warning. Thus, short-term, but orderly planning, often provided a more rational way to navigate through the conditions of being homeless.

Implications

So, what does all this tell us? Whilst policy documents talk of rough sleepers in ways which still echo distinctions of deservingness, recently they have also spoken of rough sleepers as having ‘off track’ or ‘off course’ and ‘chaotic’ lives. However, rough sleepers themselves talk of their own lives not as ‘chaotic’ or ‘off track’. Within their accounts, rough sleepers highlighted the difficult conditions and circumstances which being homeless carries. They described attempts to manage these, employing various strategies and attempts to maximise the limited means and resources available to them at the time. These are essentially ‘management tactics’ – and while they may initially appear ‘chaotic’ or ‘illogical’ to outsiders, understood in context they reveal themselves as being rational. As such, whilst policy makes judgements about rough sleepers’ lives as being ‘chaotic’ and ‘off track’, these often misunderstand the lived experience of sleeping rough. Instead, a policy strategy which recognises the importance of individual context and experience, and supports the use of personalised rough sleeper-led approaches, could provide a successful platform for understanding the experiences, strengths, and self-defined needs of rough sleepers, and could be key to reducing repeat homelessness.

*All location, service, and individual names have been changed to protect the identities of those involved in this research.

Dan McCulloch, The Open University