Tenants in danger: the rise of eviction watches

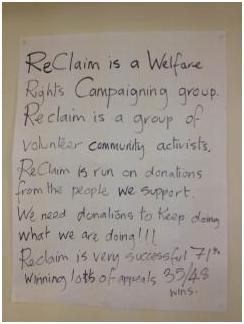

Poster at ReClaim’s welfare advice clinic in Liverpool.

Not since 1915 has private housing tenure been so dominant. The gradual rescinding of public housing over the 20th century sees us exposed to the raw edge of the market today. We are living in the darkest time of housing commodification as this project shifts from one of aspiration to coercion. With an unprecedented growth in evictions across the UK, tenants are increasingly being removed from their properties to release the value of the land.

This rise of evictions has resulted in a wave of resistance. Protection here, rather than statutory, comes in the form of “eviction watches” organised by community campaign groups and volunteers. Local campaign groups are mobilising to protect tenants facing eviction from bailiffs, gathering outside their homes to ward off any who might try. In this piece we are, firstly, casting light upon the prevalence of eviction watches today as housing privatisation and austerity take full grip. In so doing we are, secondly, raising critical questions about the state’s role and responsibility in evictions and the disparities in power between state-sponsored bailiffs and anti-eviction campaign groups who are providing short-term protection and intervention for tenants.

Eviction watches: then and now

100 years apart, the Rent Strike and New Era estate campaigns have discomfiting echoes and revealing differences which expose the degradation of housing regulation and increased privatisation over the course of the 20th century.

In 1915, housing, provided in a deregulated market, was a source of conflict between the state and tenants. Profiteering private landlords increased working-class household rents in the hope of capitalising on the influx of munitions workers as part of the war effort. With tenants unable to pay these rising rents, eviction notices were filed by private landlords, enforced by the Sheriff Officer with police back-up. In response, thousands of tenants mobilised and went on rent strike. The victory of these strikes resulted in the Rent Restrictions Act 1915, which froze rents at pre-war levels and paved the way for the Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 and later, council housing development which long since protected tenants from the vagaries of the market.

In current recessionary times, conflict between the state and tenants has been reignited and the might of the private rented sector, reinstated. In 2014, New Era housing tenants in London mobilised and campaigned against a large transnational corporate takeover by an $11bn asset management firm, Westbrook Partners. When New Era tenants received a letter from Westbrook’s solicitors informing them that their current stable rents would be raised to “market rates”, members of the community campaigned hard and fast to stop the takeover – and won. A key difference between the rent strikers’ and New Era’s victory is that the latter’s win relates only to the estate. As such, New Era are facing new challenges as the current owners of the estate – Dolphin Square Foundation – plan to means-test new tenants in order to determine rents.

What is also different is that, unlike the housing market of 1915, landlords are transnational; London is a goldmine for global property speculators and homeownership. Despite the role the housing boom played in the financial crash in 2008, property is a highly lucrative asset in austerity Britain. Private landlords, not rent strikers, are today’s unsung housing heroes, as claimed by former housing minister Grant Schapps. Bailiffs are also having a renaissance, gathering to celebrate their success at the £4,000 a head British Credit Awards in London recently. How is business? With 42,000 repossessions a day and 115 evictions a day, business is good, very good.

We are exposed to the coercive side of housing commodification and the market as authorities across the UK, with an absence of any statutory protection against evictions. Rarely do evictions take place without police presence, including riot police, serving to criminalise tenants and anti-eviction protestors. And increasingly coercive tactics of violence and intimidation are being deployed against those resisting and protecting tenants against eviction. The power mobilised by the state in the eviction process is disproportionate compared to the support offered, resources and advocacy available for those facing eviction. This, we argue, is an act of state violence on tenants and mortgaged homeowners as police forces and private security firms are utilised to facilitate evictions, shut down protesters and aid private developers and landlords.

As such, we highlight the rise of eviction watches across the UK, drawing from the frontline work of welfare campaign groups, ReClaim in Liverpool and E15 Focus Mothers, London. Like the function of food banks, eviction watches are local, voluntary support, providing a stopgap and temporary buffer for those facing a point of crisis.

They have become a critical aspect of welfare support group’s activities given the unprecedented increase in arrears. What follows is the authors’ account and observations of these two front-line campaign groups, documenting some of their experiences of working with tenants facing eviction. This sheds light on the state’s role in evictions and the disparity in power between the state-sponsored bailiffs and the anti-evictions groups.

Tenants in Danger: Mobilising Housing Action

We visited ReClaim’s Friday afternoon welfare rights clinic, 12 days before Christmas, in 2014. A couple come in for advice on their mortgage arrears. Their house is to be repossessed in 5 days time. They are £70,000 in debt and unless they can pay £17,000 upfront they will be evicted.

Juliet, one of the welfare rights volunteers, considers their options by process of elimination. She asks them why they couldn’t make the initial arrears repayment agreed by the bank and whether they can raise £17,000. The main breadwinner is a bricklayer, who is self-employed but struggles to get by being paid “by the brick”. His partner works part-time as a dinner lady on a zero hours contract. Faced with degraded and insecure job quality, repossessions disproportionately affect working-class mortgage borrowers.

Having exhausted their options with the bank’s repayment scheme, Juliet gives them two more options: one is to go down the homelessness route and live temporarily with friends and family until they find something else. The couple look disheartened; they want to be at home for Christmas. There is no statutory duty preventing repossessions which they can call upon. Although various “support for mortgage” schemes exist, people are often in denial about losing their home that many do not seek help until crisis point. The significance of this is echoed by Juliet who claims that, “quite often tenants don’t know why they’re facing eviction; they’re not informed by anybody, least of all by the social landlords. And it’s hard for anyone to come here and say ‘can you help me?’ because they’re ashamed of being of in debt and in needing help and support.”

Juliet offers the second option: “…we call round and get some ‘bodies’ in front of your house, stand in front of your house and get them off your backs until after Christmas…?” The couple look at one another tentatively. The woman puts her hand over her mouth in disbelief that ReClaim could help stall their eviction. At this point for the family, Christmas is plenty. And yet the local authorities failed to negotiate such a reprieve with the debt collectors. As promised, the advisors got to work, summoning networks, liaising across social media and mobilising a strong crowd of 40 to 60 volunteers to hold a vigil outside the couple’s home. This peaceful anti-eviction support resulted in the bailiffs, with police, being turned away. The couple were subsequently informed that the eviction notice served for that day, had been dismissed and the family had that much needed reprieve until January.

Juliet reports that they are busier than ever, due to rent arrear issues and changes in benefits. As a campaigning welfare rights collective and eviction watches form one of their many activities and caseloads are creaking. Of 50 “bedroom tax” appeals they have taken on, they have won 36 – a 72% success rate. ReClaim are by no means alone in these activities. According to another campaigner in London, Jasmine Stone, from Focus E15 Mothers, mobilising anti-eviction support now plays a vital role in their day-to-day campaign activities. She claims that, “we’ve never been so busy, we go to housing meetings with families who are being evicted and rally round at their houses to prevent them from being evicted – we just stand with our hands tied together so they can’t get through.”

In 2008, when the financial crisis unfolded, evictions amongst mortgage repossessions peaked at 142,741 in England and Wales. This followed an era of housing aspiration underpinned by Right to Buy and the availability of 100% mortgages. We are seeing similar peaks in evictions in the rented housing sector: 170,451 evictions (including private and social housing) in England and Wales in 2013, a 26% increase since 2010. In the 3rd quarter of 2014 (July-September), there were 11,100 landlord repossessions by county court bailiffs. According to the Ministry of Justice this is the highest quarterly figure since records began in 2000.

The labour power and might mobilised by the state in the eviction process is disproportionate compared to the support offered and the resources and advocacy available for those facing eviction. While previously, anti-social behaviour was the leading cause of eviction notices this has been superseded by rent arrears. Rather than working on behalf of their tenants who fall into arrears, statistics show that housing associations and local authorities – supported by housing legal experts – have resigned themselves to a very anti-social housing policy, regularly dispensing “notices seeking possession” to tenants. In 2012-2013, local authorities in England and Wales evicted 6,140 households, 81% of which were due to arrears. In 2013-2014, social landlords issued 239,381 notices seeking possession for rent arrears alone – a 22% increase from previous annual figures.

Authorities across the UK are deploying increasingly violent and intimidating tactics against those resisting eviction. In a bid to evict sitting tenants from Chartridge House on Aylesbury estate, Southwark Council called in the riot police to derail the anti-eviction protest, resulting in the arrest of six people. Jasmine Stone confirmed that authorities are escalating levels of violence and “getting really intimidating with us and there are kids present”. She recalls when campaign members attended a public meeting at the local council offices to support a woman, with child, who was scheduled to be rehoused in Liverpool (from London). Jasmine claims that “security were really aggressive, they punched one of the mums [a campaigner] in the face…”

And what is to become of the evicted? As the above suggests with moves from London to Liverpool, it’s a displacement merry go-round. Plus, those evicted as a result of arrears are, according to homeless and housing law, intentionally homeless and therefore disqualified from meaningful housing support. Those lucky enough to pass the homelessness test are no longer given priority access to social housing: since the Localism Act 2011 they are offloaded to the private rented sector. At best, this smacks not only of a withdrawal of state level responsibility to rehouse tenants in affordable housing, but a redistribution of wealth from the state to private landlords. At worst, local authorities breach the law and refuse to follow their legal duty in accordance with the Housing Act 1996.

Southwark Council – who recently deployed the riot police to evict tenants from Aylsebury estate and, in a separate event, were found guilty of “civil conspiracy” after unlawfully evicting a tenant, leaving them homeless – have been ordered by the High Court “to stop breaking the law by turning away homeless people who apply for housing in the borough”. But let’s be clear, this foul play is not uncommon. Homeless and housing practitioners have, for years, avoided the local authority route for rehousing homeless clients due to various unlawful tactics. What is uncommon, but wholly welcomed, is that Southwark Council has been named and shamed.

From Eviction Watches to National Action

In 2015, we should expect to see a rise in tenant evictions inflicted by banks, private registered landlords and the state and more grim effects of the onslaught of welfare reforms. As such the work of welfare campaigners and advocates and their eviction watch activities become an essential local resource. Public spending cuts have negatively impacted on local support services at the same time when necessity and demand for them increases. Similar to the discussions of food banks, eviction watches should not be normalised nor be separated out as a discreet strand of inequality. The main drivers of housing inequality are welfare cuts, coupled with short term and zero hour jobs (increasing at a faster rate than permanent positions in the UK) and state regulation that promotes property development.

Today, we would do well to invoke the spirit of 1915, when rent-striking tenants recognised their exploitation and acted collectively across cities to lobby for housing equality. 100 years later we are at a similar frontier where communities and cities also recognise the erosion of housing rights. Eviction watches are not enough to assuage the harms of this deregulated housing market but these campaigns do mark the beginning, we hope, of a collective housing response of similar historical and radical significance.

This article first appeared on 17 April 2015 at Open Democracy, https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/kirsteen-paton-vickie-cooper/tenants-in-danger-rise-of-eviction-watches

Vickie Cooper, The Open University and Kirsteen Paton, University of Leeds