Hostile environments and the politics of un-belonging

This week I became a British ‘citizen’. While waiting to affirm my allegiance in the official citizenship ceremony, and like so many times in recent months, I thought about what this new status meant for my rights and my identity. But, also like so many times before, I thought about the many people trapped in liminal spaces, existing but without being recognised, unable to move or stay, asked to fill out papers that will be rejected, pushed into bureaucratic labyrinths that can return them from where they escaped. Fellow human beings who, like me, were born in any part of the world by accident. Like me, with hopes and dreams. Where do we belong? And who decides it? For some, these are rather philosophical questions. For others, literally a matter of life and death. And, in between, a myriad of struggles, sometimes endured in the privacy of one’s silent journey through life, others through collective understandings, often invisible, or perhaps turned into social movements of resistance, claiming for the right to be – to belong.

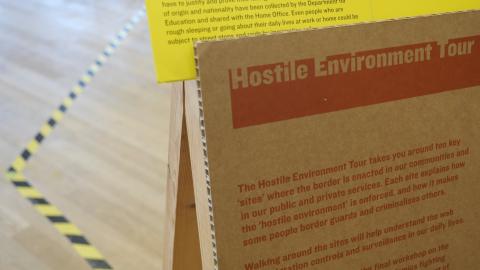

These are the questions, the spaces, the lives, the injustice that Who Are We?, a collaboration between The Open University (OU), Counterpoints Arts and Stance Podcast, helped to make more visible through combining arts, activism and academia at the Tate Exchange. A symposium on hostile environment policies against migration and the politics of un-belonging shed light on what these policies mean for people’s lives and for democracy.

Through the presentations and lively discussion, the members of the panel showed how the overarching headline of ‘hostile environment policies’ translates to have a varied impact. It can mean you are denied free healthcare in the middle of your cancer treatment, which happened to Mo, a member of the Migration and Asylum Seekers Forum. It means that as a woman facing domestic violence you might be denied accommodation but offered a flight ticket home (even if the law doesn’t allow it), as Sandhya Sharma from Safety 4 Sisters explained. It means the tools and support to seek legal aid are being stripped away. It means you lack voice, are disconnected and isolated from those campaigning for you whilst you are in a detention centre. It means asking doctors to become police, which Docs Not Cops is campaigning against. It means hate violence perpetrated by authorities, as Monish Bhatia from Birbeck University described. It means that the immigration policies are shown as separate from, but actually part of, systemic racism and neoliberal policies, intersecting and reinforcing patriarchy and heterosexual hegemony. It means you escape war legally but your status is then taken away, like 70% of the Syrian population in Lebanon, as explained by Syrian activist Leila Sibai and stated by Human Rights Watch (2017). As OU academic and activist Victoria Canning said, “there is a lot to be concerned about, and a lot to fight against”.

I have always wondered where I belong. I have felt both privileged and an underdog, and many spaces in between. I have learnt that migrating comes with endless longing for something, no matter how privileged in your new home. I have learnt not to take any of my rights for granted and that belonging is an endless struggle. But I have felt privileged after all. I have always had a safe, private place to stay, and warmth, and food and water. I have never been denied free access to quality healthcare, or education and, with it, the essential driving force that learning is to me. I have crossed many borders many times, comfortably, knowing well I could return.

There are millions, however, that have not had this experience – forced to make impossible choices, trapped, illegal, unwanted, dehumanised, in constant fear, too close to death. And, as I became a British citizen, this week has been a stark reminder of the injustice and systemic oppression faced by many whose worth is questioned every day. If citizenship is more than a legal status, if it is also care for your neighbour and to be part of a community, as was indicated in the citizenship ceremony, then it is also a responsibility to engage in practices of solidarity. It is to report, resist and change the policies, the laws, and the everyday racist and patriarchal practices that normalise this hostile environment.

This post was first published under the Year of #Mygration Open University series: www.open.ac.uk/mygration.

Anna Colom, The Open University