In conversation with Southern Criminology

Eleni Dimou (Open University)

Anthony et al (2021), in their recent response to the blog by the lead-author of Southern Criminology, Professor Kerry Carrington (2021), set out what the decolonial criminological path looks like for Indigenous communities and for researchers conducting research with and for Indigenous struggles. They speak from the positionality of migrant and Indigenous scholars in Australia to show the importance of decentering and delinking from Western canons of criminological knowledge, which were shaped during and justified colonial rule. The delinking from these canons is a necessary move to break away from contemporary manifestations of coloniality evident in the constant criminalization and pathologizing of Indigenous populations, their knowledges and ways of being. Even though Carrington (2021) argues that one of Southern Criminology’s key aims is to “build epistemological bridges”, the judgmental classification of decolonial projects into positive and negative -with negative largely being the works that have exercised constructive criticisms towards Southern Criminology- is arguably not the way forward to build those bridges. This paper follows Bhambra and Holmwood’s (2021) argument that there can be no theoretical advancement without dialogue and aims to remind that for cognitive and global justice to emerge, it requires not only the humbling of modernity but also the humbling of ourselves in that process. This involves both the positioning of ourselves (who is speaking, wherefrom and for whom) and the need to listen, understand and learn from one another (Vázquez, 2020). Therefore, the article aims to open a conversation with Southern criminology in the hope that bridges can be built.

Southern Criminology and de Sousa Santos

One of the key scholarly influences for Carrington’s (2021) arguments is the work of de Sousa Santos. Arguably, her classification of decolonial projects into positive and negative stems from a contradiction in de Souza Santos’s line of thought. De Sousa Santos (2020: 226) argues:

The epistemologies of the South call for a theoretical and methodological work having both a negative and a positive dimension. The negative dimension consists of a deconstructive unveiling of the Eurocentric roots of the modern social sciences on the basis of which the sociology of absences can be conducted. The positive dimension is twofold: on the one hand, it implies the production of scientific knowledge ready to engage with other kinds of knowledges in the ecologies of knowledges required in the social struggles; on the other, it calls for the identification, reconstruction, and validation of the non-scientific, artisanal knowledges emerging from or utilised in the struggles against domination […] Decolonial theories, for example, have been successful in accomplishing the negative, deconstructive part. Because this work has been carried out inside Eurocentric […] institutions, this work has enjoyed some visibility. The epistemologies of the South are mainly concerned with the positive, constructive work that is much harder to carry out.

Initially by seeing both dimensions as essential for the epistemologies of the South, Santos’s differentiation into positive and negative is arguably not in judgmental terms (i.e. good versus bad dimension) but rather in philosophical. De Sousa Santos is appropriating the works of decolonial scholars, especially that of Enrique Dussel and Rolando Vázquez, unfortunately without referencing. Stemming from this line of thought, the negative is about unveiling what Eurocentric modern social sciences have negated (hence the negative), whereas the positive is about affirming both knowledges that have been silenced, oppressed and rendered inferior and about listening and engaging with other knowledges essential in social struggles. De Souza Santos, despite initially arguing that both dimensions are essential in the epistemologies of the South, he then contradicts himself by saying that the epistemologies of the South are mainly concerned with the affirmation part, which is harder as it is not restricted within the academic realm but also engages with social struggles. He thus seems to take a moral judgement of good versus bad decolonial projects by raising the importance of his approach. This contradiction is highly problematic; firstly because he has two core scholars of the decolonial option, Arturo Escobar and Ramón Grosfoguel, contributing two chapters in the collective volume called Epistemologies of the South: Knowledges born in Struggle and secondly, he is drawing largely within that same chapter on the work of another core decolonial thinker, Nelson Maldonado-Torres (see de Sousa Santos, 2020: 235-236). It is beyond the scope if this paper to understand the reasons behind this contradiction, but it is evident only by looking at the two chapters by Escobar (2020) and Grosfoguel (2020) that the decolonial option engages with both dimensions of negation and affirmation. Relating to the latter, decolonial scholars have long asserted that the Zapatistas and other social struggles in Latin America have been a key epistemological departure point from which to construct their thought (see Vázquez, 2020; Escobar, 2018; Mignolo, 2000, 2018).

On Border thinking, Binaries and Race

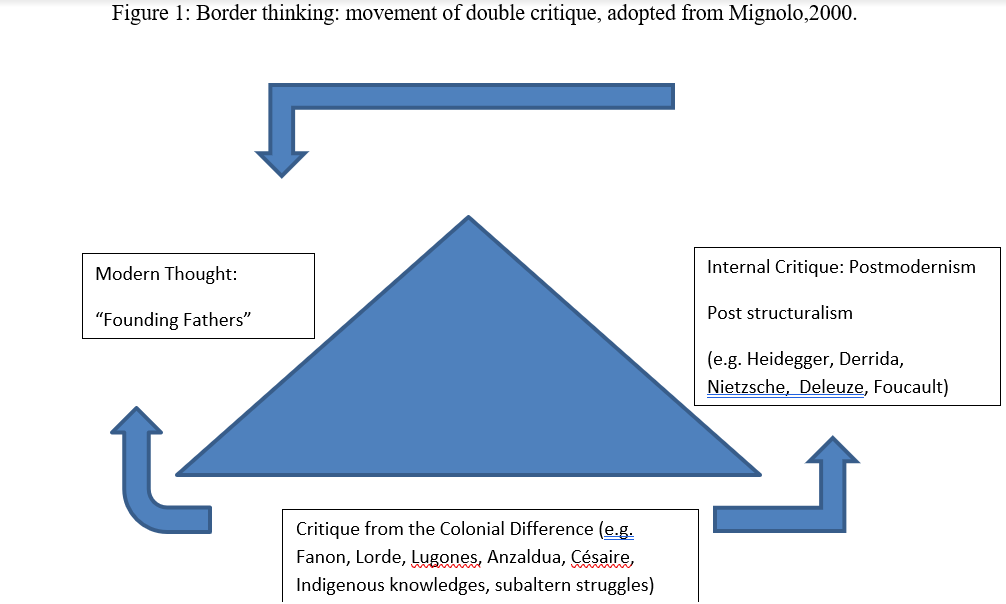

Moreover, to advance knowledge it is not only important to represent other people’s work correctly, as Anthony et al (2021) argue, but also to look at the genealogy of concepts. The term decolonial option that was used in my recent article (see Dimou, 2021) is not mine as depicted by Carrington (2021), but rather it is how decolonial thinkers themselves have referred to their approach (see Mignolo, 2005, 2008, 2018; Mignolo and Escobar, 2010). Similarly, border thinking is not a concept of de Sousa Santos as presented by Carrington (2021), but rather it is an epistemological tool coined by Walter Mignolo in 2000, in his book Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. It is crucial to understand what border thinking entails because it addresses frequent critiques made at the decolonial option that it is “in outright opposition to Western scientific knowledge” and one that reproduces “false binaries as does metropolitan thought” (Carrington, 2021). Border thinking involves a process of “double critique” of Western thought (Mignolo, 2000: 87). The first one is using and creating alliances with the internal critiques of modernity, followed by second a critique from the colonial difference (see Figure 1). For decolonial scholars it is very important to understand the internal critique of modernity to see how it functions as a deception of universality (Vázquez, 2020). The internal critique however, also constitutes a “monotopic critique of modernity itself, still “in custody” of the monotopic of abstract universals” (Mignolo, 2000:87). It belongs to the same genealogy of universality (Vázquez, 2020). Simultaneously, decolonial scholars recognise that in all their contribution, what is missing from both modern thought and its internal critique, is that they don’t address and cannot capture the colonial question. They cannot capture the erasures and the negations (see Mignolo, 2000; Vázquez, 2020). They are not concerned with coloniality[1].

In other words, decolonial scholars use Western thought. They consider it as valid, valuable thought, which is crucial to engage with and comprehend, in order to understand the internal logic of modernity. At the same time though they recognize that western thought is blind to the key question of coloniality and that is why a second critique is required from the positionality and the body-politics of the colonial difference (see Dimou, 2021). Hence decolonial thinking and praxis of living are grounded in the awareness and acknowledgement of dwelling in the borders; of dwelling in the colonial differences, which are structured on power differentials between modern/colonial Western thought and its internal critique. Thus, border thinking recognizes the canons but at the same time illuminates what has been excluded, silenced, negated and erased from the canons, through which ongoing inequalities and harms can be understood (Bhambra and Holmwood, 2021; Mignolo,2000). With border thinking, the decolonial option does not deny the canons but seeks to undo the erasures by delinking from those canons and by bringing to surface and affirming pluriversal knowledges and ways of being from the colonial difference (Mignolo,2000). The latter being a basic concept of decolonial thinking, next to coloniality, coloniality of power and colonial matrix of power (see Dimou, 2021). As such border thinking, that Carrington (2021) also opts for, involves both positive and negative dimensions. With this framework in mind, Anthony et al (2021) and Blagg and Anthony (2019), put border thinking into practice. They illuminate what has been erased by the canons of criminology and how this has served the ongoing criminalization and pathologizing of Indigenous populations, while at the same time they bring to the surface and affirm Indigenous knowledges and knowledges shaped through struggle, as de Sousa Santos (2020) would frame it.

Stemming from border thinking, dichotomies are not used in the decolonial option in terms of Western thought (bad) versus Indigenous thought (good), as Carrington (2021) seems to argue. Dichotomies are utilized in the decolonial path to “understand the functioning of the modern/colonial order. [… That is to] understand how race and gender, how modernity and colonialism have functioned as systems of exclusion” that place people in particular hierarchical relations (Vázquez, 2020: 85). As Vázquez (2020) argues, dichotomic thinking is crucial to be understood as a core feature of Western modern thought because it determines who is excluded and who is included in the various realms of society locally and globally. He moves on to state that to move beyond this order, “decoloniality does not propose, nor require dichotomies […] as ordering principles of society” and of the world (e.g. East versus West, North versus South) (Vázquez, 2020: 85). Instead, it aims to delink from that dichotomous order and to overcome it through pluriversality and relationality (see Vázquez, 2020). Hence although the South is not a geographical term for Connell, de Sousa Santos and Southern Criminology (see Carrington, 2021) but rather an epistemic term and therefore, there is a South in every part of the world, this framework nevertheless feeds into the dichotomous order of modern thought. Therefore, we may wish to move away from the binary of North and South, and to decentre and delink from the modern frames of how knowledge and cognitive, perceptual, sensual, existential and aesthetical geographies are formed within the world (Patel, 2021).

Last but not least, Carrington (2021) argues that a key problem, “with theories of decolonisation, has been the tendency to essentialise race and romanticise ethnicity […] makes invisible the gender of coloniality”. Although criticising theories of decolonisation, she then uses Maria Lugones and Madina Tlostanova, two core feminist scholars of “decolonisation theories”, among others to show how they have moved forward the decolonization and democratization of feminist theory. It is important to stress that Lugones (2010) has illuminated how the coloniality of gender functioned as a tool to exclude those racialised and those rendered as non-human. Thus, race and ethnicity are crucial for Lugones. She (2010: 743) argues:

I understand the dichotomous hierarchy between the human and the non- human as the central dichotomy of colonial modernity. Beginning with the colonization of the Americas and the Caribbean, a hierarchical, dichotomous distinction between human and non-human was imposed on the colonized in the service of Western man. It was accompanied by other dichotomous hierarchical distinctions, among them that between men and women. This distinction became a mark of the human and a mark of civilization. Only the civilized are men or women. Indigenous peoples of the Americas and enslaved Africans were classified as not human in species - as animals, uncontrollably sexual and wild (stress by the author).

As such gender and race are inextricably tied for Lugones, as gender was a feature to be attributed only to the colonisers. Colonised and enslaved people were “being animalised out of gender” (Vázquez, 2020: 70), a fact which not only legitimised perpetual violence against their bodies, but it also rendered their ways of being and knowing as inferior, primitive and savage. Thus, the race issue for decolonial thought is not about identity politics or romanticising and essentialising the “other”; but rather interrogating how colonized and enslaved bodies have been identified, classified and rendered expandable by the Western gaze (Mignolo, 2018). In doing so the decolonial option aims to challenge the structures of oppression, inequalities and exclusion embedded in coloniality (i.e. racism, capitalism, patriarchy, anthropocentrism) and which still permeate the world today.

Conclusion

The decolonial option is a path towards new ways of understanding political modernity, which means a critique of capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy and anthropocentrism of the processes that structure exploitation, discrimination and exclusion (see Dimou, 2021). The decolonial path is above all a political and ethical project that seeks to undo processes of coloniality that structure exploitation, extractivism, discrimination and exclusion in our contemporary societies and aims towards pluriversal ways of re-existing in the world (Vázquez, 2020; Patel, 2021). Importantly, as Vázquez (2020) argues, in this dismantling process of coloniality what is required is not only new ways of thinking, but also a liberation and a delinking of oneself from the dominant framework of being, knowing, perceiving and sensing set by modernity. It further requires a decolonial combativity (Maldonado-Torres, 2021); that is, the crucial path from individual to collective responsibility and within which, the will and ability to connect with others and to engage in collective struggles inside and beyond the academia. Stemming from all these, it would be favourable to see what other voices within Southern criminology feel about these issues and if they understand Southern criminology differently from what has been set by Carrington (2021) to be.

References

Anthony, T., Webb R., Sherwood J., Blagg H.and Deckert A. (2021). “In Defence of Decolonisation: a response to Southern Criminology”, British Society of Criminology blog, online at: https://thebscblog.wordpress.com/2021/11/09/in-defence-of-decolonisation-a-response-to-southern-criminology/

Blagg, H., and Anthony T. (2019). Decolonising Criminology: Imagining Justice in a Postcolonial World. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bhambra, G.K. and Holmwood, J. (2021). Colonialism and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press

Carrington. K. (2021). “Decolonizing Criminology through the inclusion of epistemologies of the south”, British Society of Criminology blog, online at: https://thebscblog.wordpress.com/2021/08/11/decolonizing-criminology-through-the-inclusion-of-epistemologies-of-the-south/

de Sousa Santos, B. (2020) Declonizing the University. In Constructing the Epistemologies of the Global South: knowledges born in the struggle. In de Sousa Santos, B. and Meneses, P (eds). Routledge, Taylor Francis Group, New York, pp, 219-239.

Dimou, E. (2021). “Decolonizing Southern Criminology: What Can the ‘Decolonial Option’ Tell Us About Challenging the Modern/Colonial Foundations of Criminology?”. Critical Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-021-09579-9

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Escobar, A. (2020). “Thinking-Feeling with the Earth: Territorial Struggles ands the Ontological Dimension of the Epistemologies of the South”. In Constructing the Epistemologies of the Global South: knowledges born in the struggle. In de Sousa Santos, B. and Meneses, P (eds). Routledge, Taylor Francis Group, New York, pp, 41-57

Grosfoguel, R. (2020). “Epistemic Extractivism: A Dialogue with Alberto Acosta, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, and Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui”. In Constructing the Epistemologies of the Global South: knowledges born in the struggle. In de Sousa Santos, B. and Meneses, P (eds). Routledge, Taylor Francis Group, New York, pp, 203-218

Lugones, M. (2010). “Toward a Decolonial Feminism”. Hypatia. 25(4), 742-759

Maldonado-Torres, N (2021). “For a Combative Decoloniality Sixty Years after Fanon’s Death”. Franz Fanon Foundation, online at: http://fondation-frantzfanon.com/for-a-combative-decoloniality-sixty-years-after-fanons-death-replay/?fbclid=IwAR0ZryQzxzKyFV1ECLkD6pYNdVkYlcaJIUyahBUUs6qtwoQag12t1As83Eo

Mignolo, W. D. (2000). Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mignolo, W. D. (2005). La Idea de América Latina: La herida colonial y la opción decolonial. Barcelona: Gedisa editorial

Mignolo, W. D. (2018). “The Decolonial Option”. In Walter D. Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh (Eds.), On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (pp. 105–226). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mignolo, W. D. and Escobar, A. (2010). Globalization and the Decolonial Option. London: Routledge

Patel, S. (2021). “Colonialism and Its Knowledges”, in: McCallum D. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of the History of Human Sciences. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4106-3_68-1

Vázquez, R. (2020). Vistas of Modernity: Decolonial Aesthesis and the End of the Contemporary. Amsterdam: Mondriaan Fund

[1] For a detailed discussion on coloniality see Dimou, 2021