You are here

- Home

- Research blog

Research blog

February 13, 2014

Written by Saskia

Tamper tantrum.

No that’s not a typo. Although I might be justified to be furious, sadness and disappointment are all I experience at the moment.

It’s a glorious day at the summit of Turrialba: the sun’s out, patchy cloud deck below, gases bellowing from the vents. It’s the middle of the afternoon: we’re later in the day than normal. The sun casts beautifully coloured waltzing shadows of the plume on the floor of the central crater.

It’s my last day of Turrialba during this trip and the prospect of leaving brings with it mixed feelings. All that remains now is to pic up the equipment and pack up. This will of course be followed by the excitement of looking at the data that has been collected: Did it work? What do the data tell us? What does this imply about Turrialba? About volcanoes and volcanic processes in general? How does this fit with the current state of knowledge?

As we walk along the crater’s edge towards the spot where we left the equipment (at the gassiest site we could find of course!) I try to soak up the scenery, to store this amazing landscape and the humbling sensation it bring in my memory forever. Closer to the plume we stop for a moment to ensure our gas masks are fitted properly: the stinging and burning sensations experienced when the sulphur rich plume comes into contact with moisture in the eyes and the lungs is best avoided.

When we reach the site of the equipment I am relieved to see that it’s still there. It also sounds as though it is still working. However, relief quickly turns to concern, something doesn’t look quite right. There is something peculiar about the appearance of the power cable and the gas in- and outlets.

Not wanting to be exposed to the plume too long despite our protective gear we pick up the equipment and bring them to a less fumigated location on the crater rim. There we inspect the instrument further: the outer protective layer of the power cable has been ripped off. The cap securing the gas outlet is at a funny angle and the inlet pipe sticks out further than it should. Removal of the box’s lid shows the inlet has been disconnected from the sensors, most likely through having been pulled on from the outside.

Nothing has gone missing and the instrument still works, though data collected since the damage has been inflicted is worthless. This is not how we left the instrument two days ago. What happened?

Although rare, coyote and coaxi have been seen up here. Did one pull on the bits protruding from the protective case? The equipment consists of two boxes, which were still neatly stacked when we recovered them. The lighter box, with the damage on top, presumably it would have moved if something had tugged on it. Furthermore, a check for teeth marks reveals nothing.

Perhaps it’s another mammal? Of the Homo sapiens kind? The park may be officially closed but that doesn't stop the occasional poacher finding his way in. Then there are those who live within the park. However, we are on good terms with the latter and the centre of the plume is an unlikely place for anyone to go: there is nothing there and without protective gear it is extremely unpleasant. So what happened? Was it malicious intent? Perhaps even sabotage of ‘rival’ scientists?

The data should indicate when the incident occurred. This can then be checked against webcam images, which may shed light on the matter.

Vandalism happens, whether for economic or malevolent reasons and occasionally purely for the sake of it. It’s part of operating remote equipment in the real world. However, in this case there is the possibility of sabotage, which is why I am sad and disappointed: if it is the case it shows an extreme lack of respect. I don’t take it personal but I am offended by the shear disregard for my colleagues who have worked hard on this, for science in general but mostly for those whose lives we’re trying to improve and make safer through a better understanding of the processes and the hazards.

However, until there is evidence no conclusions can be drawn. Time to check the data.

To be continued…

February 4, 2014

Check out the Turrialba webcam!

http://www.ovsicori.una.ac.cr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=43&Itemid=74

February 1, 2014

Written by: Saskia

January 9, 2014

Written by: Bethan

I have just returned from my second field season in Nicaragua, which was certainly far more eventful than the first! It started off with a lost bank card before I’d even left the UK, and we arrived in Nicaragua to find what turned out to be a few days of paperwork we needed to complete before being granted permission to work in the park. Once we were allowed in fieldwork commenced at a quick pace trying to make up for lost time. After a long sweaty two days’ work squeezed into one of putting up diffusion tubes and sulphation plates to monitor volcanic gases, we got back to find the water was off and no sign of it returning anytime soon! Famished, we headed out for diner. Later, a quick check of e-mails before bed revealed an urgent message that some the diffusion tubes were from a faulty batch, therefore their results might be compromised…great. Still no sign of any water, so there was nothing left to do but go to bed foul smelling and foul tempered.

.jpg)

The next few days went surprisingly well and I made good progress catching up with the plant community surveys I was repeating from my trip in February. Clearly the calm before the storm, as I woke up on Saturday morning not feeling at my best so took the decision to stay in the hotel, get data typed up and re-evaluate my time-plan. Unfortunately, my breakfast thought otherwise, and decided that it would be far better for me to spend some quality time with the toilet- I’d got a stomach bug. Even more unfortunately, that Saturday was a religious festival celebrating the Virgin Mary, meaning that any attempts at resting were futile in amongst a cacophony of marching bands, firecrackers and hymn singers.

.jpg)

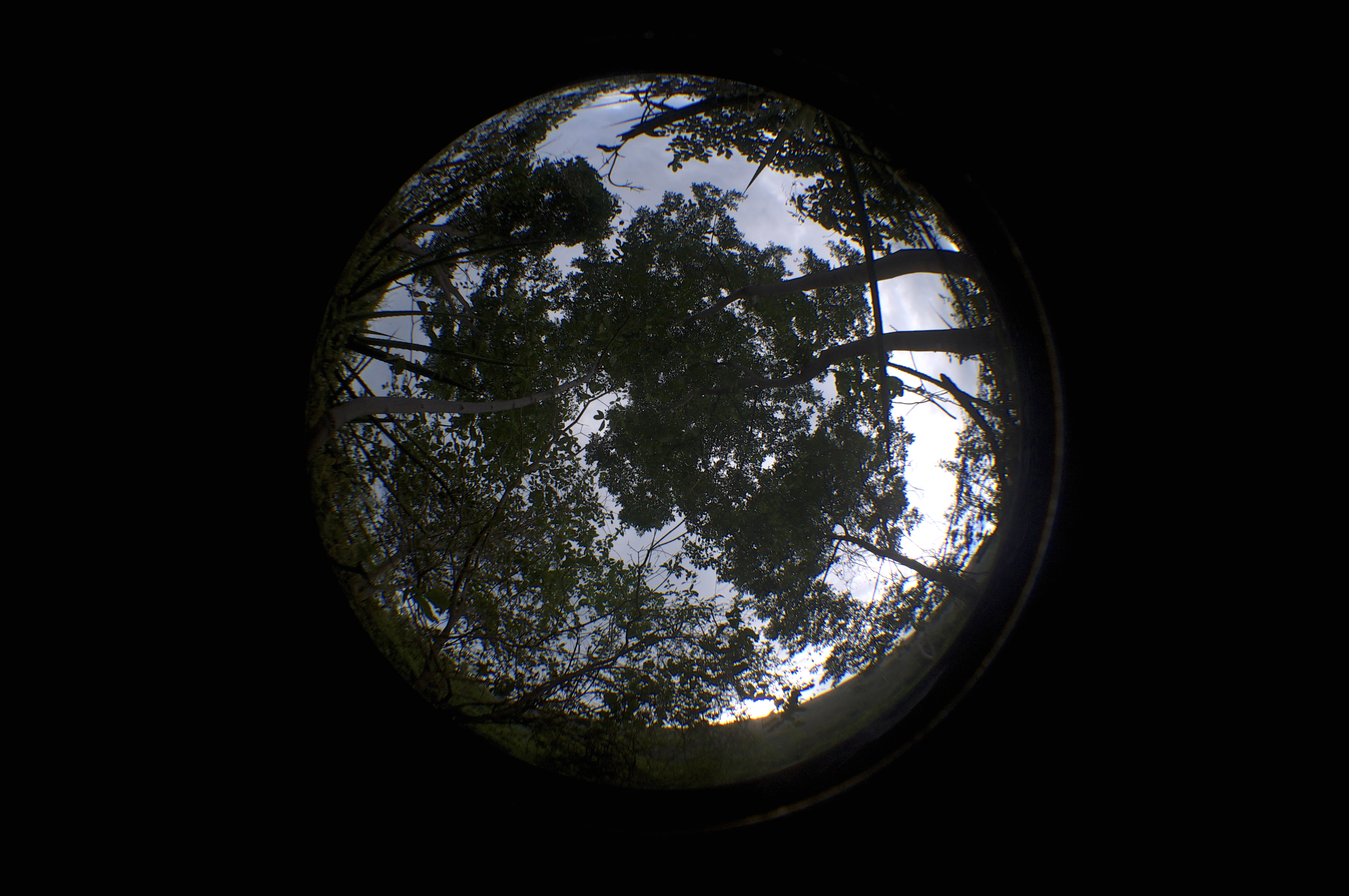

The next days’ work were slow and short as I continued to struggle to convince my appetite it existed, but I was able to get most things done. My repeat vegetation surveys found lots of new exciting species that had not been present in the dry season, and I also did some quadrats on the latest lava flows to look at colonization. Most excitingly I was able to test out a new piece of kit- a fish eye lens that attached to my camera for taking shots of the canopy. Analysis of these photos will give me an idea of the openness of the canopy and therefore how much light is reaching the understory, which is an important addition to the data I had already collected. On my final day I collected the tubes and plates, but was disappointed to find that many had been stolen. Hopefully I can learn from this and perfect my hiding skills when I take a new batch out next time!

July 20, 2013

IAVCEI 2013 has started! The International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior holds a large conference for people working on anything within their remit every four years. It's always held in a volcanologically fascinating location and this time it's no different as we find ourselves in Kagashima, Japan with brilliant views of Sakurajima volcano.

Today saw Bethan presenting on Masaya and its environmental impacts, the abstract can be found here, she did an absolutely brilliant job! On Tuesday July 23 Saskia will be presenting on the qualitative and quantitative hazards at Turrialba (abstract).

April 3, 2013

Written by: Bethan

.jpg) I spent the last month collecting data for my PhD this February at Masaya Volcano in Nicaragua. Since it was my first time there, it was full of lots of new and exciting experiences- as well as being quite daunting! I spent a month there in total, alongside other researchers and Earthwatch volunteers for my first two weeks and then alone for the remainder of the trip. It was quite a change from having lots of enthusiastic people around, constantly asking questions (most of which I struggled to answer…) to spending my evenings alone with my data! Thankfully the tough days were instantly made better by a therapeutic, freshly made smoothie at an amazing café with giant chairs!

I spent the last month collecting data for my PhD this February at Masaya Volcano in Nicaragua. Since it was my first time there, it was full of lots of new and exciting experiences- as well as being quite daunting! I spent a month there in total, alongside other researchers and Earthwatch volunteers for my first two weeks and then alone for the remainder of the trip. It was quite a change from having lots of enthusiastic people around, constantly asking questions (most of which I struggled to answer…) to spending my evenings alone with my data! Thankfully the tough days were instantly made better by a therapeutic, freshly made smoothie at an amazing café with giant chairs!

I was studying the ecological impacts of the volcanic gases, focusing specifically on the plants. I was working along a footpath downwind of the active Santiago crater named “Los Chokoyos”, meaning parakeets, who have been known to nest within the crater walls during periods of less strong degassing. I used diffusion tubes and sulphation plates to estimate emissions from the volcano along the footpath and have already found particularly high atmospheric concentrations of SO2, HCl and HF there. The sulphation plates have been prepared for analysis, and these results will show the amount of deposition of volcanic emissions, including sulphates, chlorides and fluorides. I also used a FLYSPEC, an ultra-violet spectrometer, which is driven under the plume along a road a little further downwind. It measures the amount of UV light reaching the instrument, which is greatly reduced underneath an SO2 rich plume, and therefore estimates of the total emissions from the volcano and plume direction can complement diffusion tube and sulphation plate data.

.jpg)

To consider the ecological impacts of degassing from Masaya I will be analysing plant and soil samples for their content of volcanic elements. This will hopefully show differences in uptake which might indicate tolerance to volcanic conditions. I also sampled the plant community structure, which changes from seemingly healthy tropical dry forest to a sparsely vegetated grass and shrub area underneath the plume in the space of a kilometre! So I am aiming to understand which species are resistant to the gases and how they can tolerate such a seemingly extreme environment.

The work itself was challenging, as I was mostly working along a footpath downwind of the volcano, which meant lots of walking in hot, and sometimes quite unpleasant conditions- the sulphur emitted from the volcano isn’t too kind on the lungs either, so sometime gas masks were needed. However, everyday had its new excitements- a new species of plant, bird, insect or reptile spotted along the way. On my last day, I was even lucky enough to spot the animal I’d been most looking forward to seeing - the white faced capuchin.

Now I am back to sub-arctic temperatures, it can only mean one thing, lots of time in the lab analysing my samples and hopefully finding some interesting conclusions when I can assimilate all my data together. And very much looking forward to planning my return to collect more data in the rainy season!

March 15, 2013

Written by: Saskia

Lots of news since the last post but first of all we are very happy to announce that we have received funding to continue our work from the SEG Geoscientists Without Borders program!

In October we welcomed Bethan Burson to the team, she is a PhD student who will be looking at the ecological impact of the gas plume at Masaya.

We are currently in the process of data analysis, particularly after a second succesful field season earlier this year and hope to be presenting lots of exciting results at the IAVCEI conference 2013 in Japan later this year.

Watch this space!

March 18, 2012

Written by: Saskia

.jpg) I'm at the airport, waiting for my flight, the first in a series that will see me depart Central America. From the terminal Masaya volcano stretches in front of me, a grand vista. From this distance the entire caldera is visible, the prominent caldera walls a reminder that this beauty is capable of more than suggested by its relatively small active crater and seemingly minimal degassing, which is not even visible from here. Yet when you get closer, like I have during the past four weeks, the devastation and problems that result from the persistent gas flux are obvious, compounding and enhancing socio-economic problems that this region already faces.

I'm at the airport, waiting for my flight, the first in a series that will see me depart Central America. From the terminal Masaya volcano stretches in front of me, a grand vista. From this distance the entire caldera is visible, the prominent caldera walls a reminder that this beauty is capable of more than suggested by its relatively small active crater and seemingly minimal degassing, which is not even visible from here. Yet when you get closer, like I have during the past four weeks, the devastation and problems that result from the persistent gas flux are obvious, compounding and enhancing socio-economic problems that this region already faces.

This has been a good field season, the first as part of my current fellowship. It has been exploratory: coming to grips with the volcanoes, the processes occurring and the various scales on which things operate, both temporal and physical. In addition I’m coming away with a greater understanding of the lay of the land, the communities who live on the volcanoes’ slopes and the problems they experience as a result of their geographical locations.

Quantitative results will start to emerge once I get into the lab and analyse the samplers I set out and the samples I collected. Based on the results of my quantitative data and qualitative experience I will then be able to further refine my research direction, in preparation for the next field season. There remains so much to be investigated, so much to examine, but this trip should aid in prioritising the questions to be answered & the hypotheses to be tested.

Hasta luego Masaya, Nicaragua y Centroamérica! I'll be back.

March 1, 2012

Written by: Saskia

As Einstein once said "Gravity cannot be held responsible for two people falling in love", however, it does currently stand accused of being responsible for one person falling. That person is me. In a scuffle between me, some rubbly 'A'ā lava and a steep slope, inevitably gravity won.

.jpg) After two days of thinking it was a bad sprain a trip to the hospital ensued, followed by another a few days later. Who thought my fieldwork photos would include some of these on the right. Conclusion: hairline fracture in one of the wrist bones of my right hand. Treatment: immobilisation of my right wrist for 3 weeks, or the rest of my field season...

After two days of thinking it was a bad sprain a trip to the hospital ensued, followed by another a few days later. Who thought my fieldwork photos would include some of these on the right. Conclusion: hairline fracture in one of the wrist bones of my right hand. Treatment: immobilisation of my right wrist for 3 weeks, or the rest of my field season...

February 23, 2012

Written by: Saskia

Today I went for my first ever visit to the dry forest areas in the Volcan Masaya National Park. It was amazing, there was so much to see, such a wealth of flora and fauna. A plethora of butterflies graced the trails, complemented by other species of mammals, birds, insects and reptiles, including a snake and in the distance the characteristic sound of monkeys! It makes for a welcome change from the areas of gas devastation I usually see.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

However, unfortunately even these areas aren’t free of destruction: the area we were in is subject to considerable illegal logging. One of my colleagues, Hilary from Northampton University, had walked the same trail last week and noted distinct changes in just 7 days. In places the illegal trails through the shrubs are much better defined, clearly more frequently used, than the official trail.

Dry tropical forests are rarer than the much better known tropical rainforests. This habitat now persists in less than 2% of the area it once occupied, in addition, it only covers a relatively small area of the park. These locales are true conservation hotspots.

The issue is not that straightforward to solve unfortunately; most of the logged trunks are undoubtedly used to fuel cooking fires in some of the severely impoverished communities surrounding the park. The rest of the hardwood will be sold commercially.

Although reinstating night-time patrols would be a suitable short-term solution that would prevent logging, it would also impact local families. A more sustainable answer to the problem is to provide these people with small jobs around the park: fixing fences, cleaning up rubbish (that’s a different story in itself) or tending trails. This way they’d have a small income and would hopefully learn to appreciate the value of the park, in its undisturbed state.

The latter is a form of education, which is the long-term key to conservation and development; People protect what they love, they love what they know and they know what they’re taught. Educating the communities around the volcano, whether in general or about the park specifically, is a lofty goal, in itself wrought with complications.

The old “How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time” applies here too. Hilary’s worked in the park a number of years now, always accompanied by a park guard for security. These guards have now taken a deeper interest in the park, in the science being carried out. They have started to take notes, their own photos and they can quote the number of species recorded in reports by Hilary and her colleagues back to you. They also take this knowledge, interest and understanding home with them, to their families, their children. It’s a slow process, but there is progress.

It was great to be exposed to an area of the park I didn’t know, it also opened my eyes to some of the other issues, beside volcanogenic pollution, that plague the area, how things fit into the bigger picture. Change, as with any transformation, will be slow, but it is encouraging to see what can be done. It has intensified my resolve to keep going at this elephant, munching away one small bite at a time. It’s a good thing I’m hungry!

February 20, 2012

Written by: Saskia

I’ve arrived in Nicaragua to do 4 weeks of fieldwork at Masaya! Although a lot of my work focuses on the downwind effects of the volcanic gases I decided that my first task is actually to visit the crater, it has been 4 years since I was last here and I’d like to have a rough idea of the state of things at the source. Masaya’s crater hasn’t changed a lot in the past 4 years, the configuration in the active Santiago crater just looks different. In addition, the gas flux appears lower, although this is hard to estimate visually as the visible part of the plume is in part controlled by atmospheric conditions, which have been abnormal! I experienced my first Nicaraguan rainshower, and although small, it wasn’t the last . It’s a frequeny topic of conversation among local residents too, as there have been showers every few days or so in what is normally a very dry time of the year. Can’t wait to start collecting data here though as only they will tell whether my visual assessment of the gas flux is correct, and if so, what does it mean?

February 17, 2012

Written by: Saskia

My time in Costa Rica’s up. Four weeks seemed like a lot of time to spend at a volcano, yet they’ve flown by. Overall the trip was successful, I have a much better understanding of the situation, the activity and the impact it has on the environment and the local communities. Like any fieldwork it had its downsides, with equipment breaking and malfunctioning, yet at the same time this trip has opened up more opportunities and challenges. I am leaving with more questions than I came with, but that’s the way it should be. I can’t wait to come back later in the year, search for answers once again, already knowing that although my curiosity may be partially satisfied, more queries will arise. That’s science.

February 13, 2012

Written by: Saskia

Terremoto! Earthquake! It struck approximately 75 km south of San Jose at 4:55 this morning, with OVSICORI estimating the magnitude at 6. I was asleep at the time; with a groggy head I woke up wondering what was happening. It took me a few seconds to verify that it was an earthquake, not a dream. The bed shook, the room jiggled, the windows trembled, the noise that accompanied it was the sound of everything wobbling, the metal roofs clanging, dogs barking. Next door I heard some small things tumbling. I lay there, warm and cozy, assessing the shaking: Was it getting worse? Should I take action? Then it stopped. Silence returned, an unsettling feeling taking hold: was this just a small quake that occurred nearby, or a much larger one further away, that has caused damage, casualties? Will there be more? I won’t know until I reach OVSICORI in the morning, TV screws swarming around like bees. Thankfully little damage was reported and the aftershocks were too small to be felt. Just another sign of being on a dynamic planet, above an active subduction zone, the same one that’s responsible for the volcanoes I’m studying.

February 9, 2012

Written by: Saskia

There is one thing about volcanoes that I think sparks excitement, happiness and an overall feeling of delight in a volcanologist’s heart: that is incandescence. There is nothing quite like it, seeing that hot orange red glow. It’s the heartbeat, the essence, of the very object we’re studying. Yes, large lava flows of incandescence are gorgeous, so are the fire fountains produced by Strombolian activity, but even a red glowing vent, a few meters in diameter, on giant of a volcano, is enough to provide a certain feeling of joy and exhilaration .

This evening I was privileged enough to stay at Turrialba until after sunset. First of all the sunset itself was stunning, vibrant colours reflecting off the clouds below (due to its height Turrialba’s summit’s frequently above the clouds), highlighting the plume in a rainbow of colours as time progressed. Slowly the incandescence became visible, a visual reminder of the fact that Turrialba is a living, breathing, hot volcano. It was cold up at Turrialba’s summit, the wind robbing me of feeling in my fingers and toes, it was late, it had been a long day, yet just seeing that glow, from a distance, was enough to feel content and blissful. Volcanologist one of the 10 worst jobs in the world (http://www.popsci.com/scitech/gallery/2009-01/worst-jobs-science?image=42)? I don’t think so!

This evening I was privileged enough to stay at Turrialba until after sunset. First of all the sunset itself was stunning, vibrant colours reflecting off the clouds below (due to its height Turrialba’s summit’s frequently above the clouds), highlighting the plume in a rainbow of colours as time progressed. Slowly the incandescence became visible, a visual reminder of the fact that Turrialba is a living, breathing, hot volcano. It was cold up at Turrialba’s summit, the wind robbing me of feeling in my fingers and toes, it was late, it had been a long day, yet just seeing that glow, from a distance, was enough to feel content and blissful. Volcanologist one of the 10 worst jobs in the world (http://www.popsci.com/scitech/gallery/2009-01/worst-jobs-science?image=42)? I don’t think so!

February 1, 2012

Written by: Saskia

Turrialba’s Costa Rica’s most voluminous volcano. It’s large, it’s a beast. I knew that, getting anywhere on it can take a long time, it’s easy to blame the roads (or lack thereof!). Yet you don’t fully realize, or appreciate it, until you step away from it. That’s what I did today by going up neighbouring giant Irazu volcano. It wasn’t until I was there, with a clear view to Turrialba’s degassing summit that it truly sunk in, all I could utter was ‘Wow’. Turrialba’s huge, and what’s more, the area that’s being impacted by the very gases that I am studying was very clearly visible.

.jpg)

It was great just to take a step back, admire the big picture. Sometimes the big picture is what we lose track of, when we’re bogged down in the smaller bits that we’re studying. Yet it is also worth realizing that all we’re doing is playing a small part, and that we could never be where we are, or do what we do, without the help of others, so here’s a big “THANK YOU!” to my colleagues at OVSICORI, particularly Maria, Jorge and Geoffroy, without whom lots of this work would have been impossible.

January 24, 2012

Written by: Saskia

I smell like a rotten egg, am smeared in dirt that sticks to my sun cream and am tired BUT I've got my first data!!! It's very exciting, 4 months after having started my fellowship I'm finally collecting the information I've been preparing for.

Today was my first visit to Turrialba since 2008. The changes are immense; where there were lush green volcano slopes before now all that remains are the dead white brittle remnants of trees.

Turrialba has changed; from being the BFG (Big Friendly Giant) to a growling, yet sleepy, monster. It has three craters, with the current activity limited to the west crater. There, its three active bocas (mouths/craters) furiously spew out volcanic gases, making a roaring, thundering sound. When you're on the crater rim you can feel the ground tremble. It's an awe-inspiring experience, one that I feel very privileged to have gotten.

.jpg) Though I am not here as a tourist, so soon sight seeing gives way to equipment. My eyes squint against the bright sun to make out the programs on the screen of the field laptop but soon the numbers start rolling in. It’s thrilling.

Though I am not here as a tourist, so soon sight seeing gives way to equipment. My eyes squint against the bright sun to make out the programs on the screen of the field laptop but soon the numbers start rolling in. It’s thrilling.

Then its time to don some more PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) and with a full face mask I enter the plume. A nasty cocktail of mostly water vapour, with an olive of more interesting species, swirls around me; the numbers get more exciting as my clothes get smellier.

When I pile into the car at the end of the day I feel happy, satisfied: as a volcanologist I don’t think days come much better than this one: beautiful weather, a beautiful active volcano and interesting data. Let’s hope it’s the sign of a great start to an amazing field season!

Contact us

Email: STEM-EEES-Enquiries@open.ac.uk

Department of Environment, Earth and Ecosystems

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

U.K.

Tel: +44(0) 1908 653739

Fax: +44(0) 1908 655151