You are here

- Home

- Happy Encounters - 4th Time Lucky

Happy Encounters - 4th Time Lucky

by John Zarnecki, The Open University

March 1986, July 1992, January 2005, November 2014 – different dates, but the same place. ESOC to the cognoscenti – otherwise the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt Germany, or Europe’s “mission control”. It is from here that Europe’s scientific space missions are controlled and the place to which I have been drawn by 4 incredible adventures which have shaped my professional career.

Although the European space programme has been in existence for approaching 50 years, it was really not until the early 1980s that Europe developed the technology and more importantly the strategy and the confidence to embark on space projects of real significance. At that time, the first apparition of Halleys’s comet in the space age approached. Halley is the best known comet, its orbit well-known and the comet reliably active – an ideal target for a space mission and ESA took the bold decision for a close flyby, something that had never been attempted before with a comet. I gave up a secure post in the aerospace industry to take up a 2 year contract at the University of Kent, Canterbury as Project Manager for one of the 10 scientific instruments on board Giotto, so exciting and daring was the project (the 2 year contract turned into 19 years!). The instrument was DIDSY, the Dust Impact Detection System, under the leadership of Tony Mcdonnell at UKC. After launch from Kourou and a 9 month journey, Giotto headed towards Halley on a collision course at a closing speed of 68 km/sec! ESOC had never seen anything like it. 10 teams, the great and the good from ESA and many of its member states and large numbers from the media were gathered there. We were clustered around our test equipment (which would now be found in a museum) waiting for the data to come in – or would the craft be lost by the battering from the dust particles that we knew surrounded the comet. At 68 km/sec, a sub-mm particle would have been enough to destroy the spacecraft! 2 hours to closest approach, and different instruments started to detect the influence of the comet – the magnetic field disturbance, the ionized gas, etc. We heard the whoops and cheers from our colleagues. But our screens remained stubbornly blank - an endless series of zeroes! But then, at -92 minutes, a solitary “1” appeared in one of our channels – the most important “1” of my career. We were starting to detect cometary dust particles hitting the front shield of the craft and our various sensors were “picking them up”. We were cheering like mad as the impact rate slowly crept upwards, knowing however that this dust flux was likely to destroy the spacecraft. The action got frenetic and then at just some 14 secs. from closest approach (we were targeting a miss distance of 600km), the spacecraft data stream suddenly disappeared. But we were ecstatic. We had got closer to a comet than anyone had ever achieved and all instruments had been flooded with data. We didn’t know what it all meant but we had some very exciting data that would occupy us for the months and years ahead. So the champagne started to flow. But amongst all the merriment, a voice piped up about 10 minutes later to say that some data was beginning to trickle in again! Amazingly, the craft had been severely battered by its close encounter with Halley but not destroyed. Gradually over the next hour, full communication with the satellite was re-established and data came in as Giotto receded from Halley – though it was clear from the data that the instruments had been bruised by the encounter with the comet.

Europe’s first ever interplanetary mission had been a success beyond our wildest dreams – and amazingly it was decided to re-target the spacecraft, via a flyby of the Earth, for a secondary cometary encounter. So 6 years later in 1992, we again gathered at ESOC – this time with our original test equipment long retired but otherwise much as before. But now Giotto had lost its eyes, the camera having been irreparably damaged, and several other instruments only partially functioning. But this event was a real indication of Europe’s growing stature in space and of our growing confidence that we could do exciting and challenging things – these were not just the property of the Americans and Soviets any longer! The encounter with the second comet, by the name of Grigg-Skjellerup, was never going to have the drama of the first event. However, it was scientifically enormously successful. In the case of our DIDSY instrument, at Halley we detected some 30,000 dust impacts – at comet GS, a mere 3 reflecting the much lower activity of the comet!

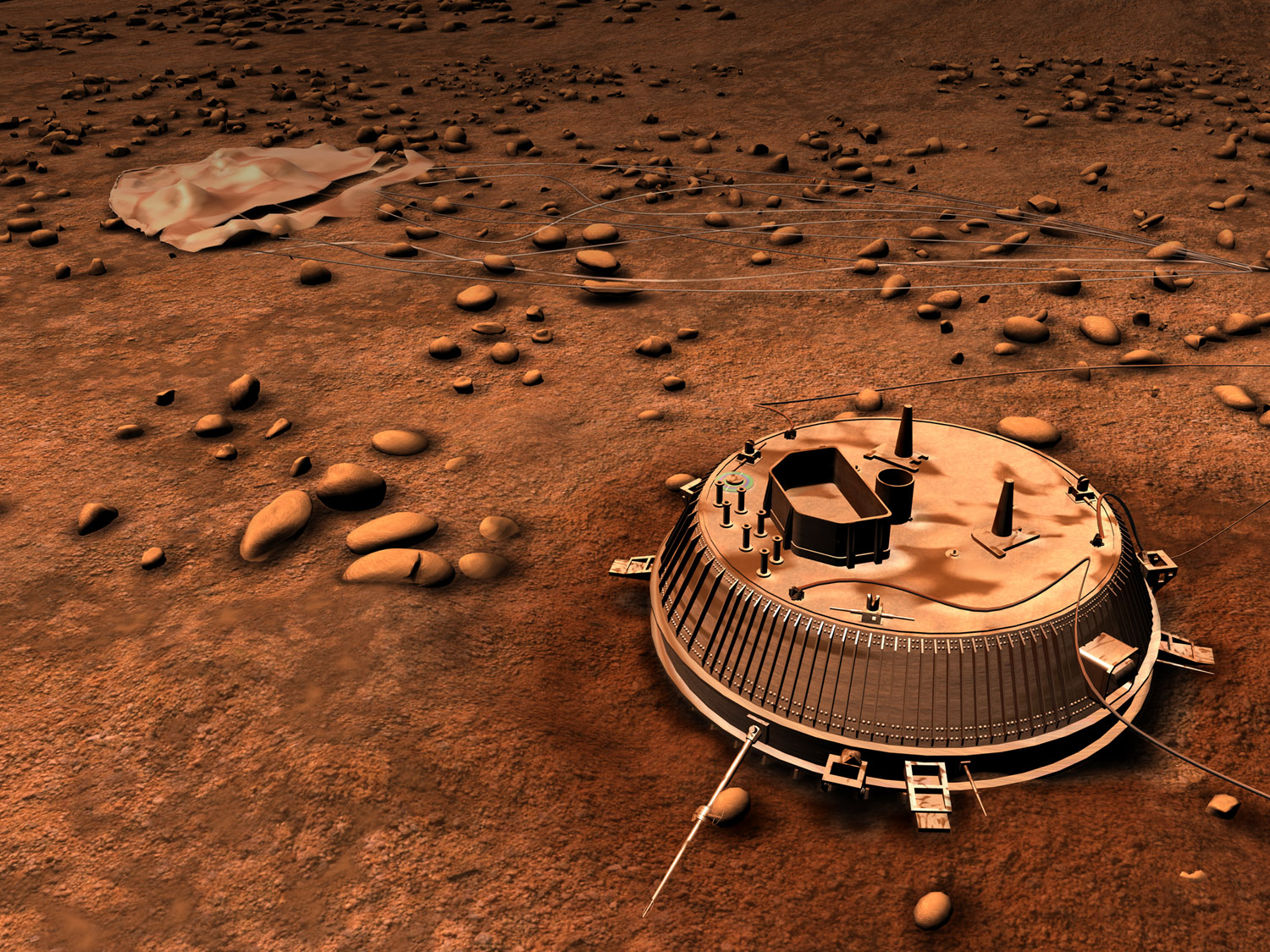

By this time, I had already embarked on my next great voyage and one that would probably define my professional career. With its growing confidence, ESA had got together with NASA to come up with the Cassini/Huygens mission, a daring trip to Saturn and its mysterious large moon, Titan. Titan was known to be the only moon in the Solar System with an atmosphere, and though shrouded in orange smog, there were indirect indications that the surface was covered with lakes or even seas of liquid methane. ESA agreed to provide a probe, called Huygens, to be delivered by the NASA carrier craft Cassini to parachute through the thick atmosphere and land on the surface of Titan. I was selected to provide one of the 6 scientific instruments on Huygens, the Surface Science Package or SSP. Leading my team for 7 years of design and build and then 7½ years of journey to Saturn was the most demanding, stressful but ultimately rewarding experiences of my professional life. So after a nervous separation of Huygens from the Cassini craft on Christmas Day 2004 and set on a collision course with Titan, we again gathered at ESOC for the fateful attempt at the most distant controlled descent and landing ever attempted. Having invested so much physically and emotionally into that venture, the expectation and tension was almost unbearable. With a delay time for the signals to travel from Titan to Earth of around 90 minutes, it was a very strange feeling to know that whatever was going to happen had already happened but we didn’t yet know about it! On this occasion, I was with some of my team in the main Control Room at ESOC, monitoring the data coming in via the Deep Space Network. The appointed hour when we expected the first indication that we had successfully survived the high speed entry, deceleration, descent under the parachutes and landing came and went with nothing! I, along with many others, thought that the venture had ended in failure. But then, a couple of minutes later than expected, the screens lit up and data started coming in. At first we didn’t know what it meant – and didn’t care! The fact that we were getting anything meant that the most dangerous part of the arrival had been successfully negotiated and Huygens was floating gently down under the parachutes. The feeling of elation was almost unbearable. Who could have imagined that those delicate scientific instruments – and our beloved Huygens Probe – which we had all got to know so well, had survived a 3.5 billion km journey and was now in one of the most exotic locations in our Solar System. As we strained to understand the data in real time, we realised that the Probe must be getting close to the surface – and then my Project Manager, Mark Leese, shouted out that we had touched the surface, and in fact data continued to come in. The incredible had happened – we had descended for 2hr 28 mins and then survived landing to collect another 72 mins of data on the surface – way surpassing our expectations. We spent the next several years analysing our data and finding that Titan was indeed as exotic as we had hoped it would be.

And so I find myself again travelling to ESOC – at the time of writing on the train from Bern in Switzerland to Darmstadt. It’s now back to Comets as Rosetta is going to attempt tomorrow to put its lander, Philae, on the surface of a comet – Europe again leading the way in cometary science! I don’t have the same close personal and emotional involvement as I did with Huygens. But I was very involved in the early days of the project so it is close to my heart. At UKC, we held the very first scientific meeting of the project way back in the summer of 1986 in the euphoria of the successful Halley encounter. This project has its origins in that time frame. Our group successfully proposed 2 instruments to the mission, originally even more ambitious as the Comet Nucleus Sample Return mission! Our instruments were successful in the severe competition for inclusion – but less successful in the competition for funding (losing out to our deadly rival, Colin Pillinger at the OU!). So although I continued as a Team Member, my personal involvement was less. However, I had become involved in the inevitable political and strategic side of things through membership starting in the early 1990s of ESA’s influential Solar System Working Group. This exposed me to the often tortuous political and financial battles that often have to be waged to make missions like this happen. But these have given me a real sense of ownership of this mission which surely belongs to all of us in the European space science community. So less than 24 hours to go. I know there will be tears tomorrow - but will they be of joy or desperation. Watch this space.

John Zarnecki

Giotto co-I (1981-1986)

Giotto Extended Mission co-I (1986-1992)

Huygens PI (1990 -2005)

Rosetta co-I (1993-2014)

Contact us

Any media enquiries should be directed using the links below:

The Open University

Science and Technology Facilities Council

jake.gilmore@stfc.ac.uk

http://www.stfc.ac.uk/mediaroom