You are here

- Home

- Natalie Sirett, Natalie Shaw and Joanne Reardon

Natalie Sirett, Natalie Shaw and Joanne Reardon

Natalie Sirett is a multimedia artist. She has exhibited extensively at home and abroad, most recently at the National Portrait Gallery, London and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. She illustrated Sita Brahmachari’s When Shadows Fall (2022), which was Times and Guardian Book of the Year and nominated for the Carnegie Medal. She is a Stirling Maxwell Fellow for Text & Image Cultures at the University of Glasgow.

.jpeg)

Natalie Shaw is a poet who has been described as ‘wonderfully bananas’ by the Times Literary Supplement. Her most recent collection, Dirty Martini, was published in 2023 by Broken Sleep Books. Her first collection Oh Be Quiet was published by Against the Grain Press. She has been commended in the National Poetry Competition and shortlisted for the Bridport Prize.

Joanne Reardon is Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at The Open University. She works extensively with visual artists on site-specific projects in museums and art galleries including Warrington Art Gallery and the Corinium Museum, Cirencester. Her novel, The Weight of Bones, was shortlisted for the 2017 Cinnamon Debut Novel Award and publishedby Cinnamon Press in 2020.

In this conversation for Practitioners’ Voices in Classical Reception Studies, Joanne Reardon talks to Natalie Sirett and Natalie Shaw about their book project Medusa and Her Sisters – a collaborative, illustrated work featuring sonnets by fourteen poets. Natalie Shaw and Joanne Reardon both contributed poems to the collection; all were written in response to Natalie Sirett’s artwork. The book was launched together with an exhibition at Burgh House Museum in Hampstead in October 2019. The conversation was recorded online on 3 April 2023.

A PDF file of this conversation is available for download.

Joanne Reardon: Welcome to you both, Natalie and Natalie, and thank you for agreeing to this interview for our Open University journal Practitioners’ Voices. We’re talking today about the wonderful book project Medusa and her Sisters. Could we begin by discussing how the project came about? Where did the idea come from?

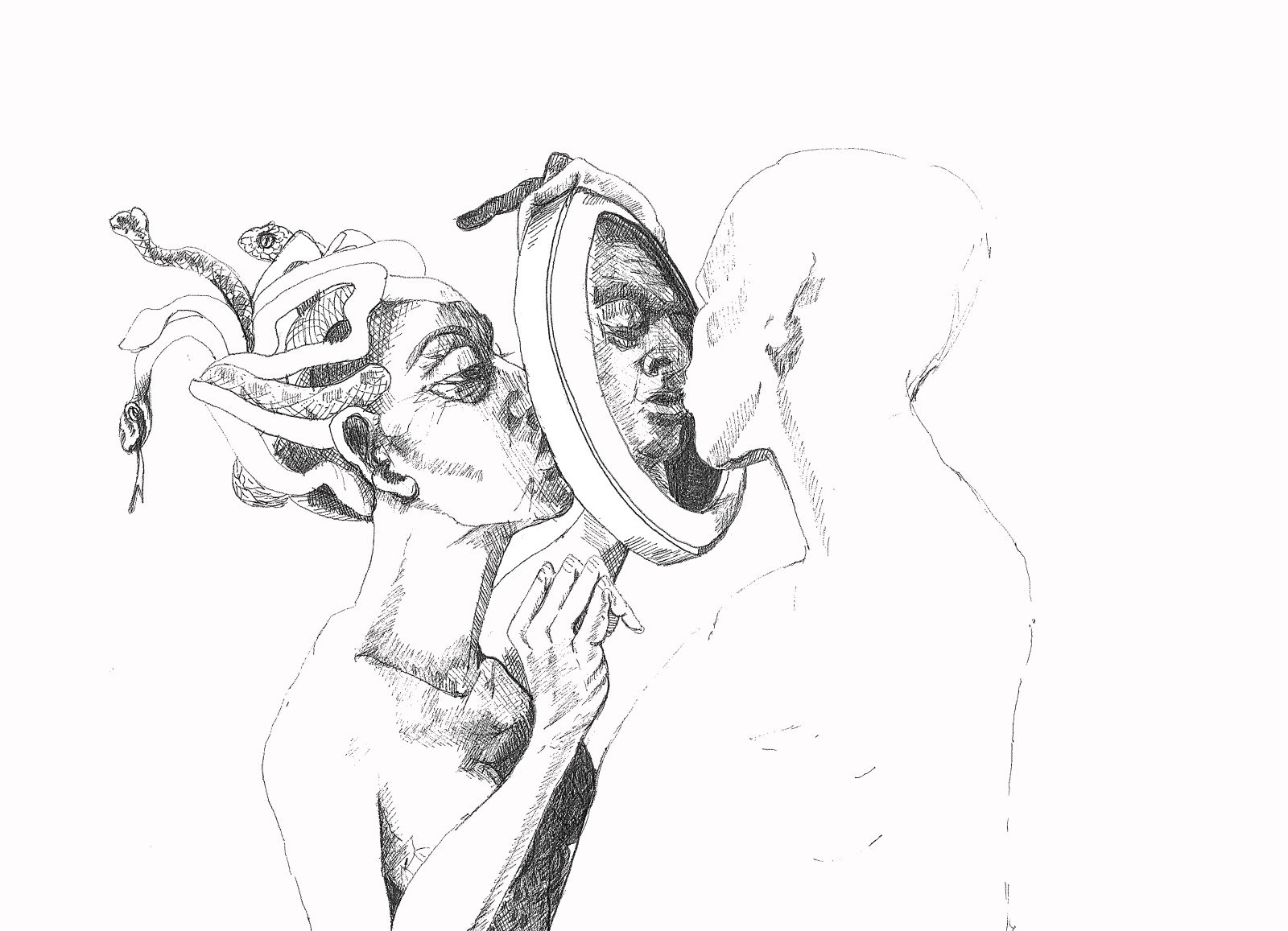

Natalie Sirett: It began because I began to get some drawings in my head. They tend to just arrive, I'm afraid! I was thinking about the Medusa, and about the technicalities of ‘how do you kiss someone if when they look at you, they turn to stone?’ I was just thinking about it as a purely practical problem. And I did a drawing, Medusa’s First Kiss – which is in the book – of Medusa putting a mirror in between her face and her lover's face and him kissing his own reflection.

Medusa’s First Kiss, ink on paper, 21 x 29 cm.

At the time I was also feeling incredibly angry about the level of body image shaming and the things that young women were going through. I thought things would have moved on from being a girl arriving in adolescence in the mid-seventies, and the kind of attitudes that were around then.

And then I found out that Medusa had sisters, Stheno and Euryale. I started reading the primordial myths, and that was where it came from. I began to do lots of drawings, and I informed Natalie Shaw that it would be really, really good to do something with them.

Natalie Shaw: I really, really, really wanted to do something with amazing Natalie Sirett whose art I’ve grown up with. I mean, literally grown up with. Behind us on the walls…walking into this place we’ve moved into [Natalie is referring to her new home here], it’s almost a gallery of Natalie Sirett’s work! I've always really loved Nat’s art because I don’t always know what's happening in the paintings in sort of literal terms, but they always speak to me in some other way. So I was very excited at the opportunity to do something together because I had often wondered ‘is it possible to do something with poetry and Nat’s art, and what might that be?’

And it was a Medusa project as well. Again, that’s something I've kind of grown up with, reading mythology. I used to go to sleep at night going through this dictionary [she indicates the book – M. Stapleton’s 1982 Hamlyn Concise Dictionary of Greek and Roman Mythology] and cross-referencing this myth with that myth, this family with that family…so it’s always felt very accessible to me, in the same way that fairy tales feel very, very accessible. And so the idea of this was really exciting.

I think also at the time my life in poetry was newish, in that I had only really started writing poetry in 2014, so at the time, it felt…it still feels very new and exciting, but it felt particularly new and particularly exciting, and like a world I was finding all sorts of new connections and things in. So it felt like a really great opportunity.

Joanne Reardon: How did you choose the poets to invite to contribute to the collection?

Natalie Shaw: I wanted people who had a response to Nat’s work. So I wanted to extend invitations to people if they felt something spoke to them in the images I was sharing. I asked people whose work I admired, some of whom I had met and some of whom I had never met and only knew through their poetry and some of whom Natalie suggested as well.

Natalie Sirett: I’d read some of Nat’s work and I knew that she was very, very talented, but she was so immersed already in the world and so knowledgeable about what’s happening in contemporary poetry and I think [to Natalie] you don’t do things by halves!!

Joanne Reardon: That is what makes it such a strong collection, I think. And when we think about the mythological figures of Greek mythology, Medusa is one of the most enduring, isn’t she? I wonder why that is? You’ve touched on it a little bit [Natalie Sirett] in our conversations with the idea of what you call the ‘negative feminine’. We come to Medusa with this kind of negative preconception, I think. How far do these preconceptions of her translate into a contemporary context and how does that influence your ‘re-interpretation’ of her?

Natalie Sirett: I’m drawn to the Medusa because she is an outcast. Much of the poetry [in Medusa and her Sisters] is actually about the Greek myth of her being cursed by Minerva/Athena, being cursed because she was violated [by Poseidon in the temple of Athena. where Medusa was serving as a priestess; this is the version of the myth told by Ovid]. What really inspired me was thinking about what I have personally dealt with – and what I see young women endlessly dealing with, once they move into this objectified womanhood. They are dealing with having to conceal anything that is considered monstrous in their appearance. You know, industries of hair removal and wrinkle removal, being the wrong shape and all of those things and the kind of pressures that I still see again and again piling in particular on adolescent girls, and which makes me mad. And I felt the sisters are very vague in the primordial myths but it appealed to me, this idea of a community of outcasts. You look at that, and you imagine what that life is like independent of the opprobrium of society. So I was having fun playing with seeing what would emerge.

Natalie Shaw: And I think I was very interested in the monstrousness. This idea of becoming the monster is really, really interesting because I mean, Medusa – she did nothing wrong. She was the victim in the story. A thing happened to her, but she carried the blame for the thing, the act itself by virtue of being cursed by Athena because she was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

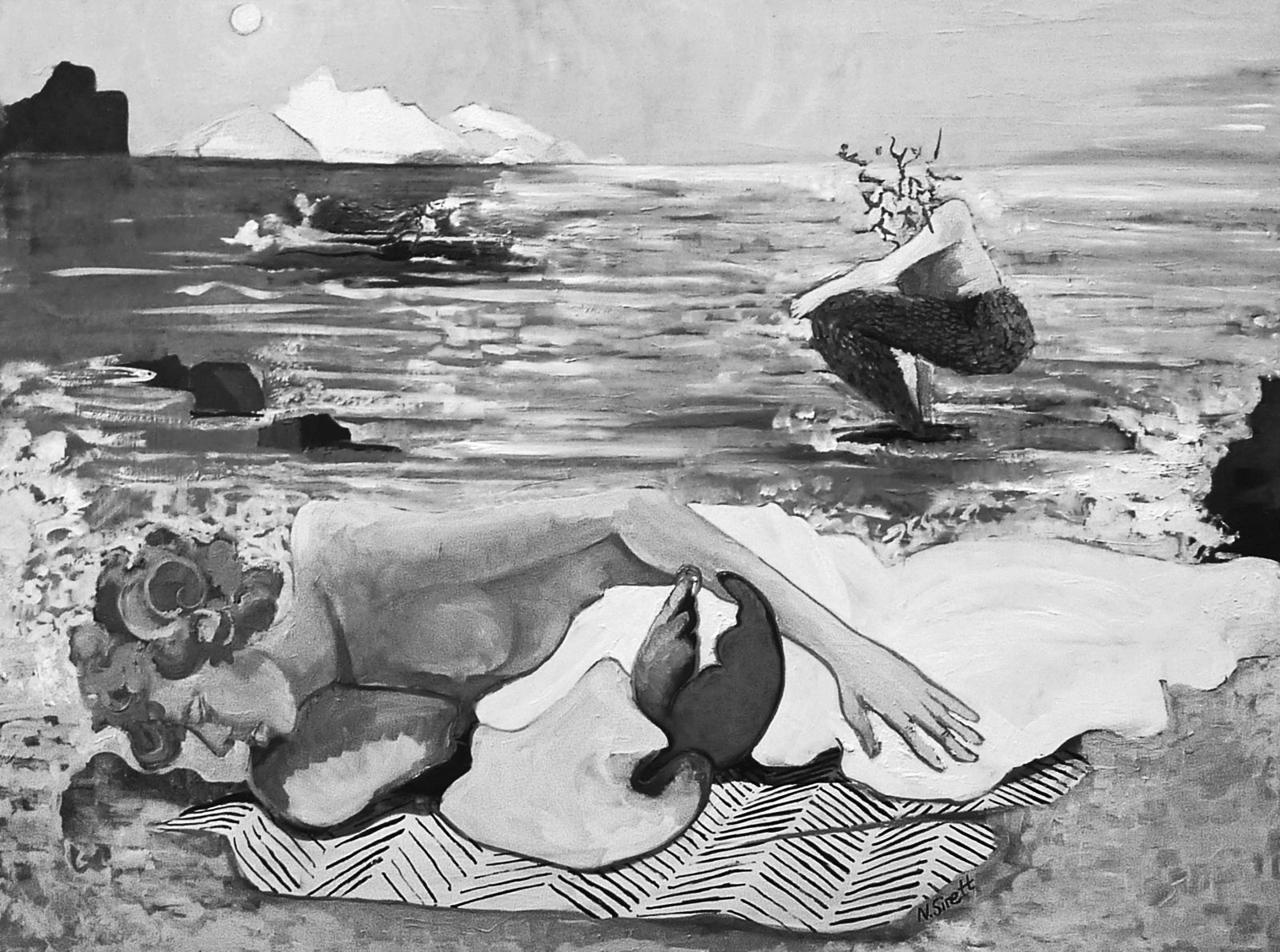

Joanne Reardon: That brings me to the other thing I was thinking, when looking at the pictures again – how much you’ve humanised them. I don’t know why that didn’t strike me before so forcefully, but it really did this time. How they don't seem monstrous at all, especially the one with the sisters at the beach, I’d not noticed [that] Medusa was swimming in the background doing her backstroke with her hair. It’s fabulous.

Medusa and her Sisters at the Beach, oil on aluminium 90 x 120 cm.

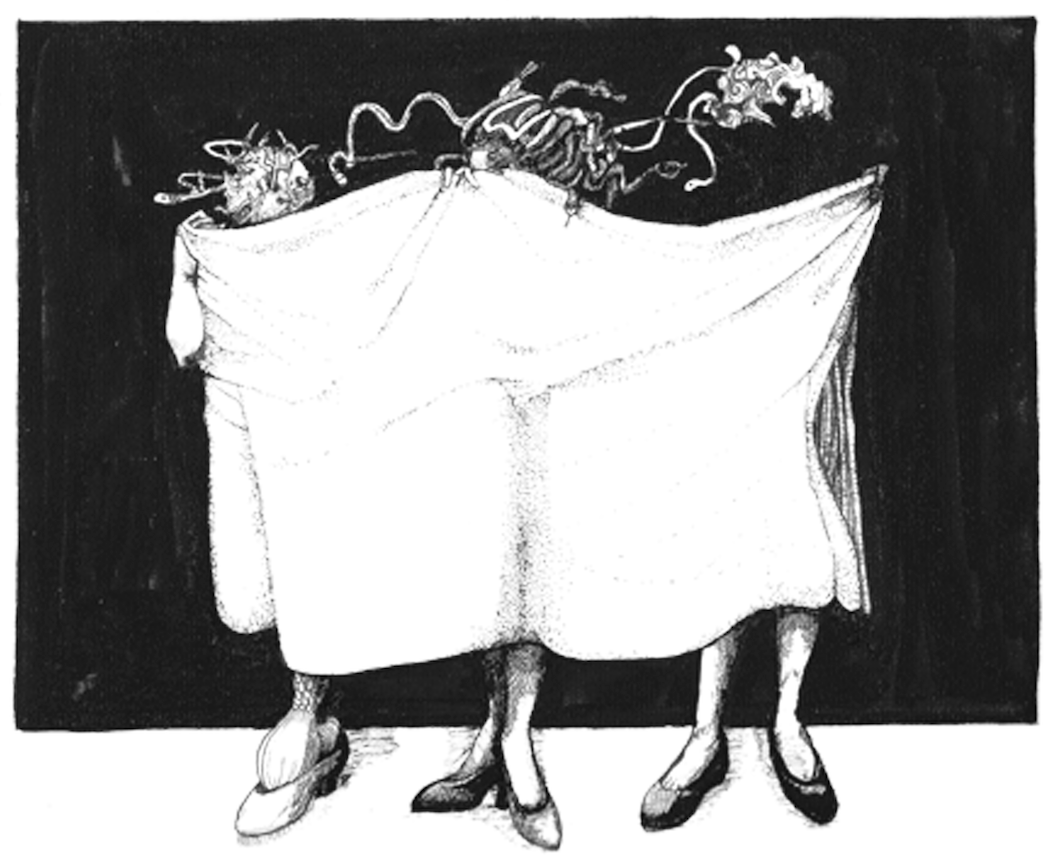

Natalie Sirett: I really wanted that particularly English kind of face where there isn't really a chin like you know, Joyce Grenfell or something (I spent a lot of time looking at pictures of Joyce Grenfell!). I just felt this is who she was. I was gleeful doing it, and I did it also with humour, because all we know is that Phorcys and Ceto, who are the brother and sister sibling sea monsters who are their parents…the father has a coral beard and a fish tail, but there’s no description of the mother that I could find in any literature that still exists. So, I loved being able to give them their characteristics. I did enjoy the drawing Dressed to Kill where they're all going to, you know, sort of turn the whole [place] to stone and down comes the sheet. But it was just a playfulness about being monstrous and saying: ‘We all feel it, we all feel monstrous on some level’. And I do believe it’s men as well as women. But it’s very particular to the women for me. You and I know about this Jo, you know, just dealing with our daughters: you have your own vulnerabilities growing up and then you see a child who is completely in tune and contained becoming something ‘other’ through those pressures.

Dressed to Kill, ink on paper 21 x 29cm.

Joanne Reardon: Some of the images are very humorous which draws a stark contrast to the ones that aren’t. Have you found any other representations of the sisters anywhere in art?

Natalie Sirett: I haven’t found any. I did contact Natalie Haynes and sent her a copy of the book and she said she was writing something about the Medusa and was really obsessed with Gorgonalia, so she was adding our book to her collection. Wow! But she didn’t know of any imagery either.

Joanne Reardon: It’s interesting that they haven’t come up in anything, not even in classical art.

Natalie Sirett: But you see, I think it’s because of who they were. Actually Phorcys and Ceto, the parents, they had the three gorgon sisters, but they also had the three Graeae, who share the one eye. So those are the three sisters of the gorgons.

Natalie Shaw: They are the ones who tell Perseus how to kill the Medusa.

Joanne Reardon: I’m just thinking as well a more recent depiction of gorgons is in the Netflix series Wednesday (2022). I don’t know whether you’ve watched it? It’s kind of Harry Potter set in a different universe, if you like, and one group of children or young people are gorgons. All of them wear turbans on their heads, and the main gorgon character is male.

Natalie Sirett: Oh I wonder why they did that?

Joanne Reardon: So it’s quite interesting what you’re saying about females, because I was wondering how contemporary it is now? I think there is an element [of the myth] that affects some young men as well.

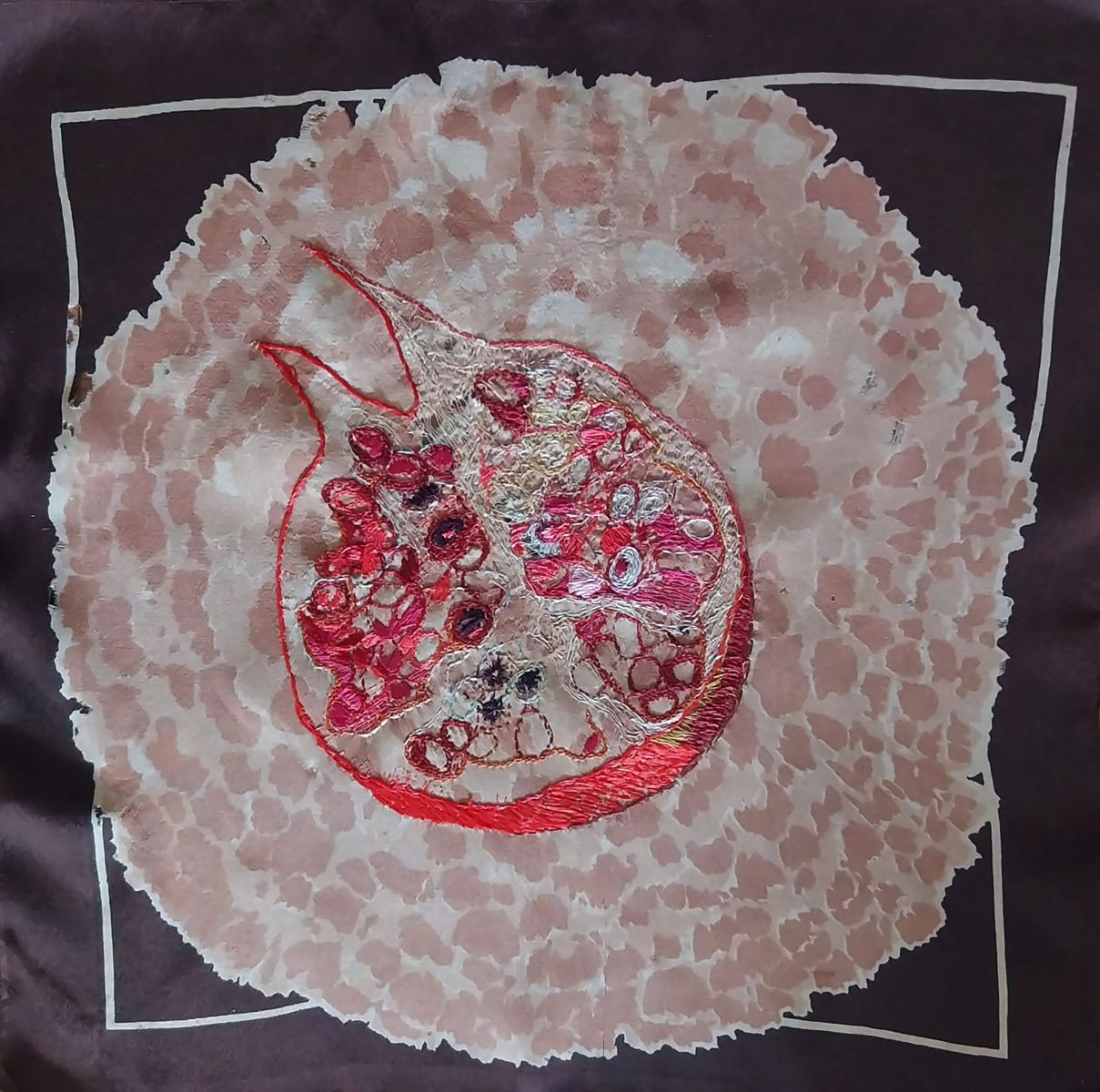

Natalie Sirett: But the wonderful thing about myths is that they’re always relevant. Margaret Atwood talks about this – how as a young woman, making her first book and flogging it to her friends at uni, she was writing about Persephone. I have literally just finished an embroidery of a pomegranate with six missing seeds. Literally two days ago, and it’s because myths belong to us, and this is why I talk about it.

Pomegranate, embroidery on antique handkerchief 15 x 15cm.

Natalie Shaw: Yes, a lot of the poems I write are about fairy tales or mythology (or, you know, that’s the seed of the poem). I remember asking for some feedback from another poet who is amazing – a person whose work I respect endlessly – who said ‘you know, you do this a lot, and perhaps you need to think about whether you are alienating people’. It’s this sort of ‘high culture’ space which Greek mythology seems to occupy, in a way that fairy tale perhaps does not so much. But I think that, because I had had this peculiar experience growing up of just immersing myself in this world…for me, it was just profoundly accessible. And now I have a teenager who’s about to do Classics at university, and it’s the same subject that Boris Johnson studied! So you can see where it comes from, this idea that stuff that’s in Latin or Greek, and that’s the canon, you know… All of these things come from a space that’s sort of saying ‘this isn't for you’. And I didn't know what to do with that.

Joanne Reardon: But there’s a real growth now, of these books that are reinterpreting Greek myth. You mentioned Natalie Haynes, and I’ve just read Colm Toíbín’s House of Names, which is about Clytemnestra, and Madeline Miller’s Song of Achilles, and Pat Barker’s Women of Troy. So I think these are all making it more accessible and more popular.

Natalie Sirett: But they are aspects of humanity, aren’t they? That’s what they are. They are icons. They are metaphors. They are symbols of life. And so of course we walk to them and hold their hands and then go into the journey of new work, or a new story, or a new film or whatever it is because they are part of what helps us understand our own human experience.

Joanne Reardon: I want to ask more about the book, and particularly the issue of giving voices to invisible women. It reminds me of Carol Ann Duffy The World’s Wife, and Janina Ramirez’s wonderful book Femina about medieval women, where she tells the stories of the medieval women whose names have been kind of erased from history.

So it’s about reinterpretation and reclaiming voices…about hearing those voices. And why the sonnet form? Why did you feel that was the most fitting form for this subject and these drawings?

Natalie Shaw: There’s something about a shape being forced onto you, which I find very interesting. A sonnet, you know, can be very constricting. Or perhaps constricting is the wrong word: they largely follow a particular structure, and you can play with that.

I wanted to give people the opportunity to be both ‘within’ and ‘without’ a sort of constriction, which sounds a bit contradictory, but it’s this idea of Medusa, and stone, and not being able to escape from something…and then the possibility of people being able to escape from the sonnet form. Sonnets are love songs, too, and often used for men to talk about very beautiful women that they would like to spend time with. I like the inversion of that, with Medusa.

Natalie Sirett: Because [the sonnet] was a little seductive, you know, to be to be performed under a window to persuade the damsels to come downstairs and to come, hither!

Natalie Shaw: Yes, sometimes I thought of it as the male gaze in poetic form.

Natalie Sirett: What I love about your poem, Jo, is that it shows how women are so often complicit in backing up the male gaze. I don’t know that I have ever met that before in writing. That’s something that rarely gets shown because it’s so brutal.

Minerva looks away

You watch him place her head down sadly, slow,

on velvet pillows cut from sea-wracked flowers.

Her blood strikes coral, sings the chime of bone.

His gesture shows this God has mortal powers,

the one man living in this sea of stone.

Jagged men who raged stare and stand now, stunned

by serpent anger etched across each face,

tied by time, decayed, rooted in this place.

Was there a moment when you could have tried

to stop him take what he had come to find,

not cowered mirror-bound behind your lies?

They punished her because you chose to hide.

They do what they do because they can,

You should know this more than anyone.

Jo Reardon

Joanne Reardon: It’s interesting, actually, because I wrote a fairly traditional sonnet, but I think I was probably the only one, if I remember rightly. A lot of [the poets] were quite free with the form, which I think was really interesting, and fitted the images.

The image I chose was Landscape with Stone Men. They were all in a row, which fits with what you’re saying about the uniformity [of the sonnet]. And that’s what I think it said to me: ‘There’s some order there, and I have to fit it within that structure.’

Landscape with Stone Men, oil on aluminium, 50 x 90 cm.

But I was thinking more about the form. John Donne’s sonnets [the Holy Sonnets] were sacred, so there’s that love of God as well. The religious spiritual element is relevant to Medusa too, because she is in the realm of the immortals, and interacts with deities like Poseidon and Athena. So there is also that sacred connection there as well. It’s a really interesting form to have chosen and quite challenging, dare I say.

Natalie Shaw Yeah, very. I think very challenging for people, and a lot of the questions from contributors were about that.

Joanne Reardon: What sort of questions did you get?

Natalie Shaw: It was often: so does it have to rhyme? Does it have to do this? Does it have to do that? What are the rules? So the questions were about the rules. And what I wanted to give back to people was the idea that you could make your own rules. If you had come back and said ‘My sonnet, it has ten lines’, I would have said ‘OK’. Or some people use the formality and use rhyme and use the iambic structure to do something really, really interesting and really, really challenging.

Joanne Reardon: But you were a very strong editor as well. It seemed to me you had a vision of how it would be. I remember all conversations we had, and it being very clear how my poem fitted in with everyone else’s. That was my impression anyway, and I think that has come out in the collection. Wouldn’t you say, Natalie?

Natalie Sirett: I think so, yes. As you know, I donated the book to the National Poetry Library, and they accept almost nothing when people send them stuff, but we got this lovely message saying ‘we really feel this collection is representing what's happening in contemporary poetry now’.

Joanne Reardon: You’ve also used this lovely phrase, Nat: ‘Writing poetry is like an act of freedom’. I love that, and it was really freeing to be able to do this, but also within the constraint. Oddly, that was the freedom – the freedom of the form really.

Natalie Shaw: Yes. And I think sometimes you need some of the decisions to be taken away from you too, to be free.

Natalie Sirett: I need the parameters, because I need to know what goes in and what I leave out. I don’t know whether I’m able to explain it well. I'm actually working with Nat’s mum to make a book about the hand, drawing on her work in psychotherapy with sand play, with people making images with objects. And she said something brilliant about the concentration of the hands. When you’re doing something artistic and meticulous which is like a passion of concentration, it allows you also to float free and think about the experience of who you truly are. And I think that’s it: there is the work and the parameters and the structure, but something in the absorption allows the floating free.

Three Disturbing Things about Tilda Swinton as The Medusa from Brief Interviews with Hideous Women

Tilda never looks at you directly

You could have stopped it

Tilda has this inscrutable beauty

All those things you did

Tilda makes you want to put your finger

What you did to let it in

On the marble palace of her cheekbone

You let it touch the whole of you

On her alabaster balustrade

Inside you

Her obedient skin an invitation

Inside you are frozen

Reach your fingers through the screen to Tilda

Frozen parts create the frozen world

Natalie Shaw

Joanne Reardon: If you’re doing writing with art, it has to match it, doesn’t it, in some way? The form has to match the image in terms of the space on the page. The poem has to echo that.

That’s the thing about ekphrastic work: you’re responding to a work of art. It has to ‘re-set’ it, not to resemble it, but it has to reflect it in some way. And that’s in the form as well. I sometimes write short stories in response to art, and I think short stories have got a lot in common with poetry.

Did anybody come up with any themes around Medusa that you hadn’t considered? Any new angles?

Natalie Shaw: In some ways, absolutely every single one. Everyone brought something different. It was really quite incredible.

Joanne Reardon: Because you weren't expecting that?

Natalie Sirett: No, not at all, I’d agree. It’s a book of fifteen voices. There’s my voice, which is drawn, but then there’s also the fourteen poets. For me, it was the worlds I got taken into as well. I was taken – sometimes so theatrically, like on to movie sets – to beaches or back alleys or temples or whatever it was, and it just felt like this enormous, delicious privilege that within a very slim volume, there are all of those journeys. So that was great.

Joanne Reardon: The book came out just over three years ago. Has anything changed since then? I know that’s an obvious question, but I just wonder, if you were doing it now, how would you approach it differently?

Natalie Sirett: I think that post-COVID, there would have to be some ramifications about isolation. And then maybe the new demands for a different view of what is normal, the new normal.

Natalie Shaw: It’s funny looking back, because it was in the October before Covid. We were just hearing about what was happening. It does feel like we’ve all lived many lives since then.

Joanne Reardon: I know, and in some ways that [launch] event evening feels like yesterday, but then I look at what’s happened since. When I looked at the collection again today and really thought about it…it’s the beginning of the conversation, and it’s a conversation that we're still having.

Well, thank you both for some fantastic answers and insights into the creation of this beautiful book.

Find out more...

Visit Natalie Sirett's website for further details of Medusa and her Sisters

.JPG)