You are here

- Home

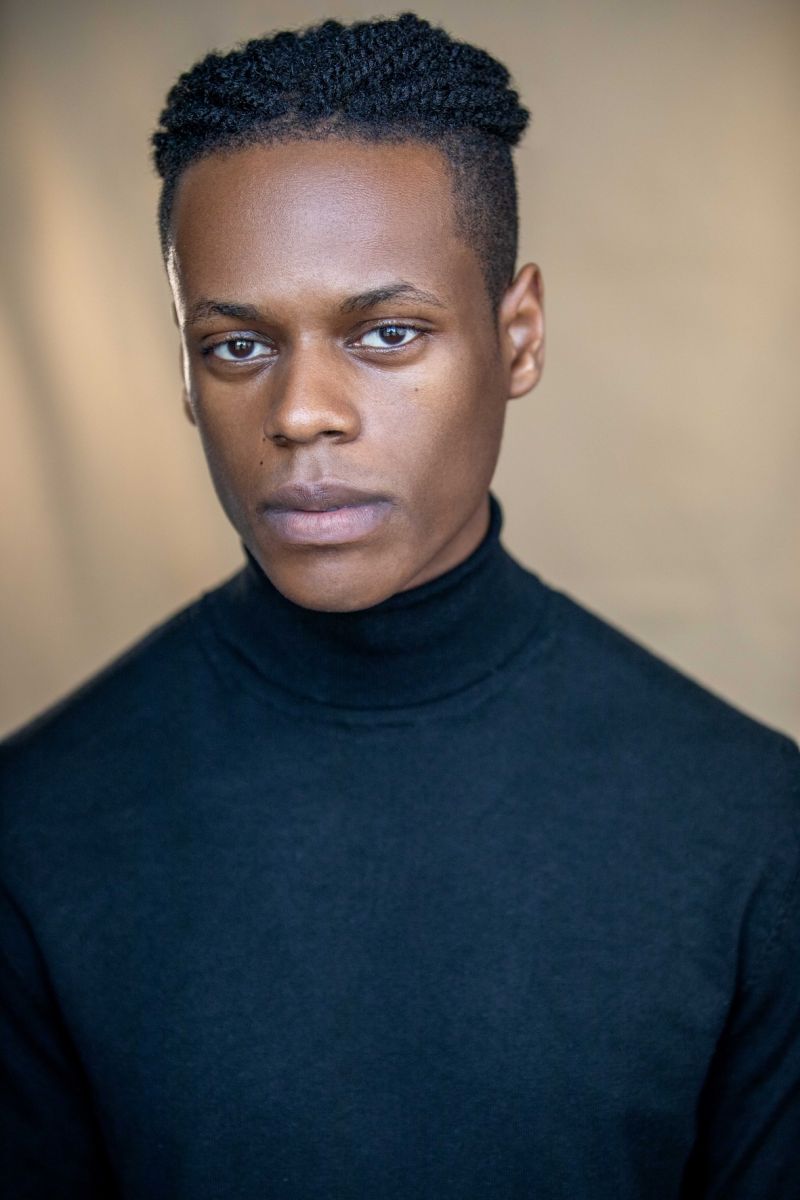

- Kwame Owusu and Katherine Soper

Kwame Owusu and Katherine Soper

Kwame Owusu directed Katherine Soper’s new adaptation of Euripides’ The Bacchae at the Lyric Hammersmith in July 2023.

Kwame Owusu’s work in theatre as a director includes Dreaming and Drowning (which he also wrote) at the Bush Theatre; The Bacchae at the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre; Othello at ArtsEd; stoning mary at Arts University Bournemouth; and The Wolf from the Door at the John Thaw Studio. He has also worked as Staff Director on Romeo and Julie at the National Theatre and Sherman Theatre. Work as an assistant director includes Closer, Britannicus, Scandaltown, and Running With Lions at the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre. Writing for theatre includes HORIZON for the Bush Theatre.

Kwame Owusu’s work in theatre as a director includes Dreaming and Drowning (which he also wrote) at the Bush Theatre; The Bacchae at the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre; Othello at ArtsEd; stoning mary at Arts University Bournemouth; and The Wolf from the Door at the John Thaw Studio. He has also worked as Staff Director on Romeo and Julie at the National Theatre and Sherman Theatre. Work as an assistant director includes Closer, Britannicus, Scandaltown, and Running With Lions at the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre. Writing for theatre includes HORIZON for the Bush Theatre.

Katherine Soper’s first play, Wish List, won the Bruntwood Prize for Playwriting 2015. It was performed in 2017 at the Manchester Royal Exchange and Royal Court Theatre and has since been produced in Germany, Turkey, and South Korea. She has been nominated for the Evening Standard Award for Most Promising Playwright, and won the Stage Debut Award for Best Writer. Other works include The Small Hours (National Theatre Connections, 2019), Calls from Far Away (BBC Radio 4, 2022), and The Bacchae(Lyric Hammersmith, 2023). She is currently under commission to the Royal Court Theatre.

Katherine Soper’s first play, Wish List, won the Bruntwood Prize for Playwriting 2015. It was performed in 2017 at the Manchester Royal Exchange and Royal Court Theatre and has since been produced in Germany, Turkey, and South Korea. She has been nominated for the Evening Standard Award for Most Promising Playwright, and won the Stage Debut Award for Best Writer. Other works include The Small Hours (National Theatre Connections, 2019), Calls from Far Away (BBC Radio 4, 2022), and The Bacchae(Lyric Hammersmith, 2023). She is currently under commission to the Royal Court Theatre.

They were interviewed in August 2023 by David Bullen, Lecturer in Drama and Theatre at Royal Holloway, University of London, originally for his forthcoming book with Liverpool University Press, Greek Tragedy as Twenty-First-Century British Theatre: Why, What, How. David had met with Katherine to discuss the play while she was in the process of writing her adaptation; he subsequently provided Kwame, Katherine, and the rest of the team with a pack of contextual information about Bacchae, ancient Athenian performance culture, and the play’s performance history.

A PDF file of this conversation is available for download.

David Bullen: What did you both do to prepare for this project? Did that preparation process differ from work you might normally do on a play?

Katherine Soper: The Lyric brought the Bacchae to me. They had done Lysistrata the year before. And I think they were wanting to continue with doing a Greek [play] but wanted to do a tragedy this time. I already knew the play, but my knowledge of it was about ten years old at this point, because when I was at university, we did a paper that was just called ‘Tragedy’, in general. We had to read every Greek tragedy and Shakespearean tragedy and a smattering of modern tragedy, so I already knew it from when I had gone through this whirlwind of having to read all of them the summer before my third year. I found the ideas that people had about Bacchae really, really compelling. So it stuck with me actually more than a lot of the other plays that I read in that very short period did. When they [the Lyric] asked me if I wanted to do it, I had this very strong feeling: with lots of other plays, like Medea, I would have felt like I'm trying very strongly to find a new angle on it that hasn't been done before. Or I’d have been casting around to see if there's something I can do with it. Whereas it came very quickly with Bacchae. I went back and found some of the well-known criticism about the play - it's the first stuff that you encounter when you look at, you know, the Cambridge Companion to Euripides or that sort of thing. I was coming at it from the perspective of a new writer, not a translator. And that made me feel a lot more happy about going in a slightly different direction - we're doing something else entirely. Those bits of historical information were very, very useful for clarifying the original theatrical intent.

In terms of whether it's different to how I normally approach things, I normally read a lot of academia for everything that I write, oddly; when I'm reading something, my subconscious brain in the back of my mind is reacting. That is a very useful way to bring ideas around in a quite organic way. With this the biggest difference was that I'd never adapted anything before. And that was the biggest change in the process – I felt like I was starting with much more of a booster step than when I'm writing completely from scratch. It felt like I had a map this time.

Kwame Owusu: We met in November. We had a conversation before Katherine started writing. I had already been thinking a lot. So we had a really exciting conversation about Katherine's initial responses to the sorts of material and then my responses to her responses. We were talking thematically and politically and about character and we were thinking about form. For me, the biggest danger with directing any classic is fossilisation or presenting something which kind of feels like a museum piece, particularly when it's such a canonical text. I think academic study is very, very important, but I think what academic study is trying to do is very different to what we should be trying to do in a theatrical setting. When you're directing a revival, the key thing is to revive – which is to bring something back to life. With that in mind, the thing that I’m first interrogating is what a play would have made the audience feel rather than what it would have made them think. At the heart of my analysis is trying to identify what the dialectic is in the play, on an academic level, and then trying to make sure or figure out ways in which that dialectic can be presented in a way which is felt rather than just critically understood from a distance. In terms of our theatrical gestures, I was thinking about how we render these in a way which also has a felt impact. Interrogation, dialectic, and then tying those back to the work - I would do that for any play. I have a set of textual and linguistic analyses that I do on every play, thinking about the gesture and conceit of a play, thinking about each character, thinking about – through quite traditional Stanislavski-like thinking – objectives and tactics and then alongside that, the socio-political analysis. And thinking about how the socio-political fabric of the world will inform character behaviour and character action. I think that’s what's exciting about Katherine's play. She hasn't just presented a translation, she's reimagined the play entirely and so the socio-political world of the characters in Katherine's adaptation feels just as important and immediate a socio-political world as the original. We have people today responding to the abuse of power and the ways in which grief is held and used by the state, thinking about relationships and rivalries and inequalities in all sorts of different ways. Things we are grappling with today. So yes, my job as I see it is about analysing and gathering and responding. And then to bring it to life in a way which feels immediate and felt, as well as, of course, intellectually understood.

DB: What both of you are saying about this project as an adaptation versus as a new play is really interesting. You wrote a really brilliant new play but, at the same time, we can understand it as an adaptation of a much older play. Did the idea of it being adaptation continue to bear weight on it? I think Katherine mentioned previously that the project came about because, I think, the Lyric wanted this to have an educative function for the actors in their training programme.

KS: I don’t know if the actors looked at the original at all.

KO: Some of them did. And some of them didn’t. I think the people who did were the ones whose characters are in the original. Makes sense. And so I think people used the original as a tool to understand their characters.

KS: The origin of where that character had been.

KO: Exactly: what’s happened to them and their history and so on. Pentheus, Cadmus, Agave. They're obviously in the original. But the chorus aren’t named in the original but have real lives in Katherine’s version, so there wasn't really a direct parallel. Part of Katherine's mission was to bring three-dimensionality into these characters. I guess, for me, I was treating it like a new play. That gets to the heart of the need for immediacy and liveness and not treating it like a museum piece.

KS: If it had been a straight translation, I think that weight of adaptation would have felt a lot stronger. I felt very free to take whatever from the original that felt useful to me. There are some small lines where that is apparent. David, because I know you know the play very well, you may well have spotted the line about seeming to see two moons, though I think it is two suns in the original. I started writing some of the final scene where it talks about holding two ideas in one fist and I was trying to tap into this kind of imagery or dichotomy that I feel is fairly strong throughout the original, so I took that line. I felt very free to lift that. It’s strange because there are some things that you initially move away from but then come back to. Initially, we didn't have that prologue from Bacchus. Then when we started talking about that after the first draft or the second draft – we were casting around for what we were missing with Bacchus and realised that was what we wanted. That was what we needed. When I sat down to look at that, even though I don't think there's any textual overlap between those two openings, I felt the gesture was very similar, and exactly what we needed. But it was also a new, different version that came very naturally. There were these moments where it felt as though it's not necessarily a burden to be adapting, because actually it feels like a treasure chest where there will be these things that suddenly you need.

KO: And we spoke about how we can equip the audience with the resources that an audience at the time would have had, by default, because the audience at the time are being inculcated with these stories. It was in the air, whereas our audience don't have that. And you want to figure out what's on the list of stuff you want to take for granted, and then the list of stuff that needs to be understood in order for the feeling to be clear. That was a major thing for me as well. Going back to the dialectic, the thing which makes the play felt is making sure that the dialectical positions have a psychological source. So it's not just that they are, you know…

KS: We represent this and I represent that…

KO: Which you see in old Greek plays, because there’s that function. But actually, by really leaning in particular into Bacchus and his grief, we found a drive for his actions. What that did was give the dialectic a psychological and human weight, even though obviously, he’s not quite human. It made it more complex and made his argument less of a straw man, because it was not just the pursuit of power. It was the pursuit of justice, which is far more understandable. I’m also thinking about Pentheus’ relationship with his mother, and the way in which he’s had to navigate power, and what impact the burdens of that might have had on his psychology.

KS: And that the greed and the grief is present for all of those characters. The humanization of the past and what’s come before the play brought that out suddenly, and I felt it brought the psychological more into focus in a way that a modern audience could engage with.

KO: Yeah, in a really rich and complex way. Every play is full of ghosts, and I think it's just the job of the artist to identify which ghosts are useful and which ghosts aren't because they're always going to be there. There’s a great quote from Anne Bogart [the influential American director, a long-time collaborator of Tadashi Suzuki] – she says that if theatre was a verb, it would be ‘to remember’. I think that’s really true. Using ghosts to provide extra fuel or extra complexity is always good. But then, on the other side, ghosts create a sense of static – so it’s about navigating those ghosts and trying to make something which feels alive.

DB: That’s really interesting. I’ve got a question that came to me when I watched the play – why, in the end, did you call him Bacchus rather than Dionysus?

KS: Yeah, this is entirely my choice. For me, it's partly that because for a lot of people there's a disconnect between what the play is called and the main character. And I think it's a surprisingly large gulf for a lot of people to work out the connection between them. I wanted to make that clearer. Funnily enough, he's never called Bacchus in dialogue, because I was quite anal in not wanting the audience to hear a Greek or Roman name and feel like they were being brought out of a setting that felt more immediate to them. People who do quite radical adaptations tend to approach this differently. You have Robert Icke who [in his 2015 adaptation of the Oresteia, originally at the Almeida Theatre, London] still called the lead Clytemnestra even though she's going on TV talking about her husband’s politics. And then you have Simon Stone [the Australian director known for his radical reworkings of classic plays, most recently Phaedra at the National Theatre] who tends to rename pretty much everybody, to give them a modern name and I think I tend to be a bit avoidant with those [ancient] names being used. With the actors it felt more right for the process to say here are the Bacchae and here is Bacchus. It felt like it unified those things: we could talk about the Bacchae, we could talk about Bacchus. But in the dialogue there's only a few instances where anybody uses the names of the original classical characters.

KO: It made me think about not naming, you know. For me, what's really effective about that is that it kind of gives the audience a licence to shrink that gap between the world that they're seeing and the world that they inhabit. Particularly with the people in power. No one's saying that Pentheus is Rishi Sunak, but there is a sense of ambiguity about that proximity. One of the things which we were exploring throughout the process of writing and rehearsals was how to capture the danger of the situation that this play is presenting. In particular, the danger that Bacchus poses to the stability of the social order and to the stability of the state. It's not just about a battle of ideologies, it’s about the threat to the state and the threat to Pentheus’ power and therefore to civilization itself. People like Pentheus and Cadmus preach that from different perspectives, but they both want to solidify and concretize their power, because of what they believe. We spoke a lot about how so much of Katherine's reimagining places those young women who make up the Bacchae front and centre, really leaning in and interrogating the arc of their radicalization through the play.

We spoke a lot about cultural materialism. Because Bacchus is the god of theatre, arts and culture is mixed in with that as well. We spoke a lot about how culture can be used to challenge the social order or to problematize the state. We spoke a lot about [Marxist theorist] Raymond Williams: he speaks about how you can divide culture into dominant, residual, and emergent culture. And so we kind of thought about how perhaps that could be a useful way of tracking both the radicalization of the Bacchae and also the strategies of radicalization which Bacchus implements. Perhaps they’re never in the dominant space, dominant in terms of culture, which is closest to the social order…perhaps that’s more of Pentheus’ world. But really, we were thinking about the journey from a counter-culturalism which is fundamentally safe and contained to a counter-culturalism that is a legitimate danger. Euripides’ play ends with them decapitating Pentheus, pulling him apart limb by limb, and Katherine's adaptation also ends with that act. Our job is to make sure that the arc of the play makes that conclusion logical. I am a firm believer that an audience will accept anything as long as it's logical: as long as the journey to get there is logical and the rules of your world are logical. And so, we had to make sure that we tracked an arc of radicalization, which meant that the final act of violence was embedded and threaded through their ideology and, crucially, could be tracked back to the roots, which was their dissatisfaction or feelings of entrapment or violence or isolation within their world, which is also the world of the audience. Ergo, this radicalization journey could happen to any member of this audience. If you also feel like society controls you or undermines you or hurts you or contains you, then you could also go on this journey.

KS: The dominant-residual-emergent triptych was really, really crucial throughout developing this as a way of differentiating between, like… doing a version of Bacchae that’s all about fandom and stan culture and things like that, or… a version of Bacchae that’s about the Manson family. It was about realising that there needs to be a kind of progression between these things. And for me, even a kind of progression beyond the cultic aspect of it into the fact of saying that this isn't just some people getting mixed up because of a standard cult leader archetype, it's something even beyond that. Having a consciousness of that tracking was really, really useful.

The final parts of that I think came out of the conversation that you and I had, David, where you said about how you've seen productions of Bacchae before that have really tried to hang their hat on one hook – it’s this kind of thing, or another, it’s Woodstock, it’s the Manson family. It works for a while – there are chinks of light where you say ‘yes, I can really see the parallel’, but then the play wriggles out of that and so out of the production’s grasp. So, I thought my quest here is to identify how slippery the play is and to make that the final thing that we look at. We were talking about making the final climax of the play logical but in some ways it’s also about making the illogical part of the play legible, the fact it's a very different kind of logic to the kind that Pentheus would like it to be. That was why the final scene was key. My writing was far more declarative in this play than anything I've ever written before. I think partly that's an influence from the Greek text. But I was so concerned that these ideas that I felt were pulsating in the play wouldn't necessarily reach an audience if we just did a standard translation, or a kind of very A to B version of it. My concern was to identify those ideas as clearly as possible for an audience. That was the origin of the final scene. The things we talked about, David, about how it’s a culture going through a paradigm shift, I wanted to basically put that on the table for an audience. It's not a just a fandom, it's not just a cult, it's something more profound than these things.

In Katherine’s version, the earthquake (which in Euripides occurs earlier in the play after Pentheus imprisons Dionysus) takes place after Agave kills Pentheus. In the subsequent, final scene discussed above, one of the women who had been with Bacchus talks with Teiresias while they help to clean up the city. They discuss the meaning of what the woman experienced, resisting its reduction to a singular logical cause or binary morality, and how Teiresias has lived through similar seismic cultural changes. The scene points to a seeming need for people to simplify what they can’t understand, to believe in ‘one single truth’, thus making it difficult to ‘[hold] two things in the same fist’.

KO: I wouldn’t say that the play is totally captured by this word, but I do think that a lot of the play can be viewed through the prism of violence: what violence is, and the different forms violence can take. It’s tracking a journey towards this massive act of physical violence, but it is thinking about the violence of change, the violence of civilisation, the violence of language, the violence of history. And all of those things I find really useful to share with the actors, because they feel really tangible. There’s a word we use, ‘playable’, phrases or words that can be used to shape someone’s performance. If I told an actor, ‘be happy’. What does that even mean? All you’ll get is a very sketched version of cartoon happiness. But if you ask someone to marry you and put your whole soul into the possibility of building a life together, then what you’ll get is a level of urgency and hope and drive that will capture a sense of happiness. Words which have a sense of process in them felt quite useful in this particular play, because it allows the actors to invest their energy in arcs and in process. Change is at the heart of this play – so as the world changes, their psychologies change, and for the actors that’s useful for them to hold on to, informing how they track through the play in their performances.

DB: This is so interesting, because the French anthropologist René Girard said back in the 70s that Dionysus is the god of violence [in Violence and the Sacred, 1972]. And scholars have argued back and forth about that. But it’s interesting to see that through practical exploration you’ve come back to an idea that some scholars have dismissed. They’re looking at this play surrounded by piles and piles of books, but you’re exploring it with bodies in dramatic space and you suddenly find that a certain idea is really prevalent. So, on that note, I’m thinking about different kinds of specialist knowledge. You’ve talked about Raymond Williams, you’ve talked about other kinds of specialist knowledge that were bubbling through the process. Obviously I gave you some materials and we were chatting about stuff, but what kinds of specialist knowledge did you feel were necessary for working on a project like this? Or, indeed, were unnecessary – not only for you, but for the cast and other creatives. Were there particular kinds of playable things that you brought in from, say, ancient contexts? Though I don’t necessarily mean just ancient Greek things, it could be other stuff as well.

KS: When I was taking things more directly from the translations of the Greek texts that I had, I was concerned that I have as good an understanding of those as possible and that they were correct, just for my own purposes. There was a line that I remember really liking from Anne Carson's version of the play. It’s when Dionysus says to Pentheus something like ‘you are a formidable man, and you will have formidable experiences’ [‘You are an amazing strange man / and amazing strange experiences await you’, Anne Carson, Bakkhai, Oberon Books, 2015: p. 51]. I messaged a friend of mine who has studied ancient Greek and I said talk me through these words that have been rendered in these ways and she said ‘this is one of my very favourite words’ [the word in question, which Carson translates as ‘amazing strange’, is deinos, l. 971]. That allowed me to be like, ‘Okay, I'm choosing something that is in the right ballpark’ when I’m taking something quite specific from the Euripides text.

KO: There are some characters in Katherine's version which are in the original and some characters which aren't, so in terms of my approach for the rehearsal room, I have to treat it like a new play. The questions that we were asking, the interrogation that we were embarking upon in terms of the themes and the ideas and the story, etc, etc, were only from Katherine's text – there was no original translation in the room, there was no looking back to it to shape discussion. Because it isn't useful for all of them. But then when we started rehearsing with a couple of actors that's when more specific contextual knowledge started to bleed in. Work that the cast had researched on their own, stuff that I brought in using your resources, David, as well. But it was only ever to get under the skin of what was on Katherine's page, what was in Katherine's text, to understand or to interrogate the behaviours and actions and relationships within the play, because those are things which are playable. We needed some information in order to fuel that logic, you know; so, understanding, why does Cadmus not just run and attack Bacchus; why does Pentheus say to his mum ‘don't speak’, but then actually does want to speak to her. Understanding these things required some contextual information, required information that is in the original. But then for the world of the Bacchae themselves, these were brand new, contemporary young women who didn't have a life in the original. And so for them, the contextual research, or the specialist knowledge, was our world today, thinking about gender politics and racial politics and societal power and the way in which power is accrued and divided in our world today. In that regard, the actors are our specialists, because they are the young women who are navigating a society today, which has been represented in the text. Rather than it being a top-down thing of ‘here is all the research I prepared as a director’; actually, it's up to me to ask questions the parallels from here to the world that you understand. Not in a way that’s like ‘tell me all your life and reveal yourself to us,’ but useful parallels which could inform your character psychology or your character's actions in this play.

KS: I do remember us having a conversation really early on with the actors where they were wanting to know about Bacchus – because I leaned very hard in the text on Bacchus actually being a god, they were keen to know about that and the kind of the worldbuilding behind that in a way that did end up touching a lot on the Euripides. I think we spoke about the prologue and how it sort of alludes to the relationship between Bacchus and Semele. I seem to remember they did want to know about who the mythical version of Semele was, and about the sort of internal world logic of a god's true form killing you. And that I felt was useful to them, the discussion that we had about that, which is kind of a bridging thing, where it is actually the same in the Euripides as in my version, because Bacchus isn't just a human, he is still a god.

KO: Obviously Katherine’s not going to say this, but for my money what makes the play fantastic, what Katherine's done brilliantly, is that the play is a study of so many individual things but it doesn't feel piecemeal. It feels like it's just studying lots of different things, in rich details. For me the play is a study of people in power, and it's a brilliant dissection of the ways in which power is haggled and bargained and held on to when negotiated. But then it's also like Katherine just said, a brilliant study of the supernatural, and how the supernatural bleeds into reality and how prophecy and faith and hope and power beyond our understanding can have a very material impact on the behaviours and actions that we take, in our world today, in ancient Greece, and also in this kind of hybrid space in between. Then it's also a brilliant study of the domestic, of domestic pains and struggles. What's thrilling about the play is that by placing all of these side by side, what it does is that it elevates all of them to the level of the epic. It means that the domestic isn't just the domestic, the domestic is also epic; it means that studying people in power isn't just haggling and backroom deals. This is the fight for the soul of a nation and the fight for a civilization. The same goes with the supernatural: the supernatural isn't just something floating around in the air, it's grounded, it's informing psychology, it's informing human beings in a very, very real way. By placing all these things side by side, it did a very difficult but brilliant balancing act of grounding and elevating at the same time.

KS: That is to me the central gesture of Euripides’ original: trying to take in both parts of any kind of dichotomy. That's the reason it's such a compelling text to work with, because all of the things you just listed, Kwame, probably are there in one way or another. It's just an incredible set of ideas and emotions to work with. One of the Lyric’s staff came up and asked, ‘would you do a Greek play again?’ I was sort of like, yes, but also… The Bacchae is so good. I would do a Greek play again, if it was the right one, but could anything be more right than this one for both the things that I am interested in as a writer (which really lined up very serendipitously with Euripides) and the richness that is at the heart of the text? It feels unlike any other Greek tragedy to me.

KO: I think because the play is doing so much, particularly in Katherine's adaptation, it means that the anchor points are the human beings at the heart of the text. And I think sometimes where ancient Greek adaptations fall down is when they lose sight of the human beings at the heart of it. It becomes just a battle of ideas. Returning to what makes this play about violence – but one that doesn’t become defined by violence – is that it's coming from this character's grief and therefore it's violence plus justice. Violence plus justice is so much more complex and murky compared to violence as spectacle, which I can imagine another version of The Bacchae leaning into. Obviously Bacchus is known as this god of ostentatiousness and the theatrical and so on, but I think violence as spectacle would do this play a disservice. Whereas violence as the logical product of rich, psychological dislocation and destabilisation works.

DB: Well, this is extraordinary. Thank you both for these comments. Can I sneak in a tiny last question? I'm thinking about the last words of Bacchae, you know, the chorus say what we expected didn't occur. How have your expectations of Bacchae or of Greek tragedy or of whatever changed, or not, as a result of working in this process?

KS: I think in some ways I’ve always seen, maybe erroneously, a bit of prestige attached to straight translations of Greek tragedies. I feel like I've now come down very hard on how much better, how much more rewarding, it has been for me to do an adaptation that leaps more into becoming essentially a new play – as in, the credit being ‘after Euripides’. I felt like I got the best of both worlds doing it this way, rather than a perfect translation. I can feel where I would have been hemmed in. There is a place for those more faithful translations, but I wish there was a bit more freedom among playwrights – there is some but I wish there was more – to start departing more strongly. There is so much you can retain of the soul [of the original play] while giving yourself the freedom to venture into areas that help express that soul more clearly and in a more individual way, depending on the writer.

KO: This whole process has really reinforced for me how important the ancient Greek texts are still. I love new writing. I’m a massive, massive advocate for new writing. But I do think that ancient Greek texts have a really important place in our ecology. And I think what they do so brilliantly is that they are some of the best studies of the human condition – of what it means to be human, how we survive being human. We haven’t really changed, fundamentally, for the last 2000 years. That’s why these plays still have such a purchase today. Ancient Greek texts bring the human condition into conversation with our culture and our politics and our world in a way that I think is really thrilling. I think plays today don't necessarily do this in the same way. Plays today do different things in different ways. I think this process has cemented for me that the role that ancient Greek texts play in our ecology is to give this really sharp, thrilling, vivid, daring insight into the pains of being human. And I think Katherine's play has done that brilliantly. I'm excited for more of that within the wider theatrical landscape.