The Mangrove Nine – Fifty Years On

Dr Andrew Gilbert, Senior Lecturer in Law, writes about the trial of the Mangrove Nine, which began fifty years ago today.

Fifty years ago today, on 5 October 1971, the trial began at The Old Bailey of a group of black men and women known the Mangrove Nine. The nine defendants – Barbara Beese, Rupert Glasgow Boyce, Frank Crichlow, Rhodan Gordan, Darcus Howe, Anthony Carlisle Innis, Altheia Jones-LaCointe, Rothwell Kentish and Godfrey Miller – faced a range of serious charges, including riot, incitement to riot, and affray. Despite the evidence of around 40 police officers, the prosecution largely failed to convince the jury of their case. The defendants were acquitted of 23 of the 32 charges, including the most serious ones of riot.

The case of the Mangrove Nine – the subject of Steve McQueen’s excellent 2020 film, Mangrove – is significant because the defendants’ radical courtroom strategy led to the first official recognition of racism in the Metropolitan Police. This article looks at the case and police efforts to challenge the judge’s controversial finding.

What was the Mangrove?

The Mangrove was a restaurant which opened in 1968 in Notting Hill in west London and was owned and run by Frank Crichlow. It was much more than a restaurant, however, and played an important role as a hub for the black community in Notting Hill. The police had The Mangrove under constant surveillance and raided it numerous times, including twice in 1969 and ten times over six weeks in 1970. The raids were based on police suspicions that drugs were being sold on the premises or that the restaurant’s licence was being breached, but they were seen by local people as racial harassment condoned by the legal system.

In response, a demonstration against police harassment was organised by the Action Committee for Defence of the Mangrove. On 9 August 1970 about 150 demonstrators, accompanied by 700 police officers, marched a route that took in three local police stations. At one point, violence broke out and serious fighting occurred between protestors and police, resulting in 19 people being arrested, including those who became known as the Mangrove Nine.

What was radical about the defendants’ courtroom strategy?

The Mangrove Nine adopted a radical legal strategy that included demanding an all-black jury, self-representation for Altheia Jones-LeCointe and Darcus Howe, and the advocacy of Ian Macdonald (barrister for Barbara Beese) who rejected the standard view of the defendant as victim.

The defendants’ application for an all black jury, based on an appeal to Magna Carta, was refused by the judge, Edward Clarke. However, defence challenges to individual juror selection were more successful, in spite of police tactics to influence the jury’s composition. Official documents in the National Archives show that the police searched Special Branch and Criminal Record Office files for the complete panel of the jury and passed relevant information to the prosecution barristers.

Jones-LeCointe and Howe decided to represent themselves so they could accurately express to the court the experiences of black people, particularly those concerning unjust treatment by the police, but also their wider social experience. They felt it is better to represent yourself, however inadequately, so that these experiences are brought to the jury’s attention.

Reflecting on the Mangrove trial, Macdonald wrote they learned ‘how to confront the power of the court and in the end to break it...because the defendants refused to play the role of victim.’ He added, ‘[o]nce you recognise the defendant as a self-active and self-assertive human being in the court everything has to change – the power and role of lawyers, the style of advocacy, and the method of case preparation.’ (Macdonald, 1977, p.156) Macdonald was in no doubt that the trial was politically motivated:

‘It seems clearly to have been an attempt by the state to prevent the growth of organised resistance within the black community which had an independent leadership; and that seems to me to have been the real point of the case.’

(Mangrove Nine, 1973)

‘racial hatred on both sides’

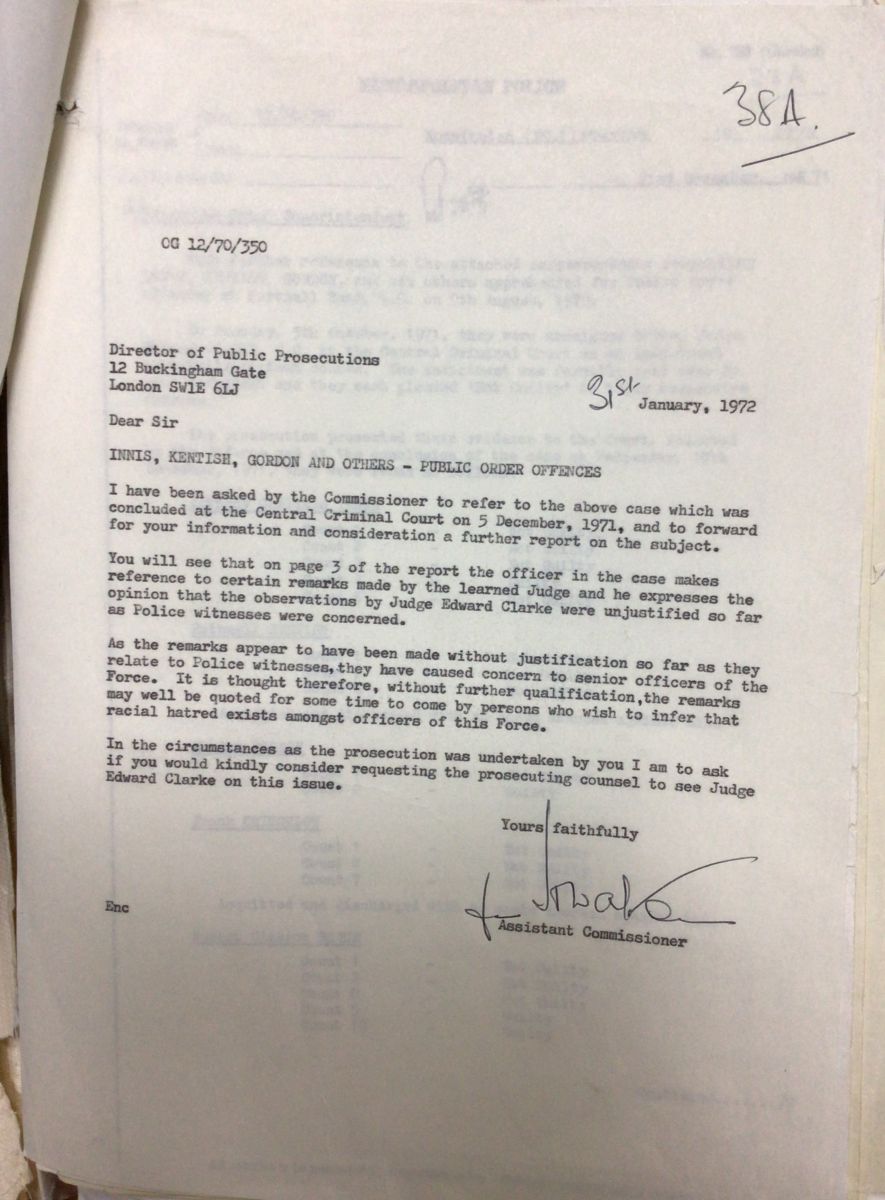

The case is also significant due to the judge’s statement that the trial had ‘shown evidence of racial hatred on both sides.’ This was the first judicial recognition of institutional racism in the Metropolitan Police and it caused some consternation across the service. On Christmas eve 1971 a senior police officer wrote an internal memo stating that the judge’s comments ‘are quite uncalled for’. In reply, another senior officer wrote the remark ‘will be used “as a stick” to beat police with for years’. The Met’s leadership clearly wanted to put pressure on the judge to retract his damaging remarks. Despite their own solicitors advising that Clarke wouldn’t play ball, the Assistant Commissioner wrote to the Director of Public Prosecutions at the end of January 1972 requesting a meeting between the judge and the prosecution barrister (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Letter from Assistant Commissioner to DPP, 31 January 1972 (MEPO 31/20)

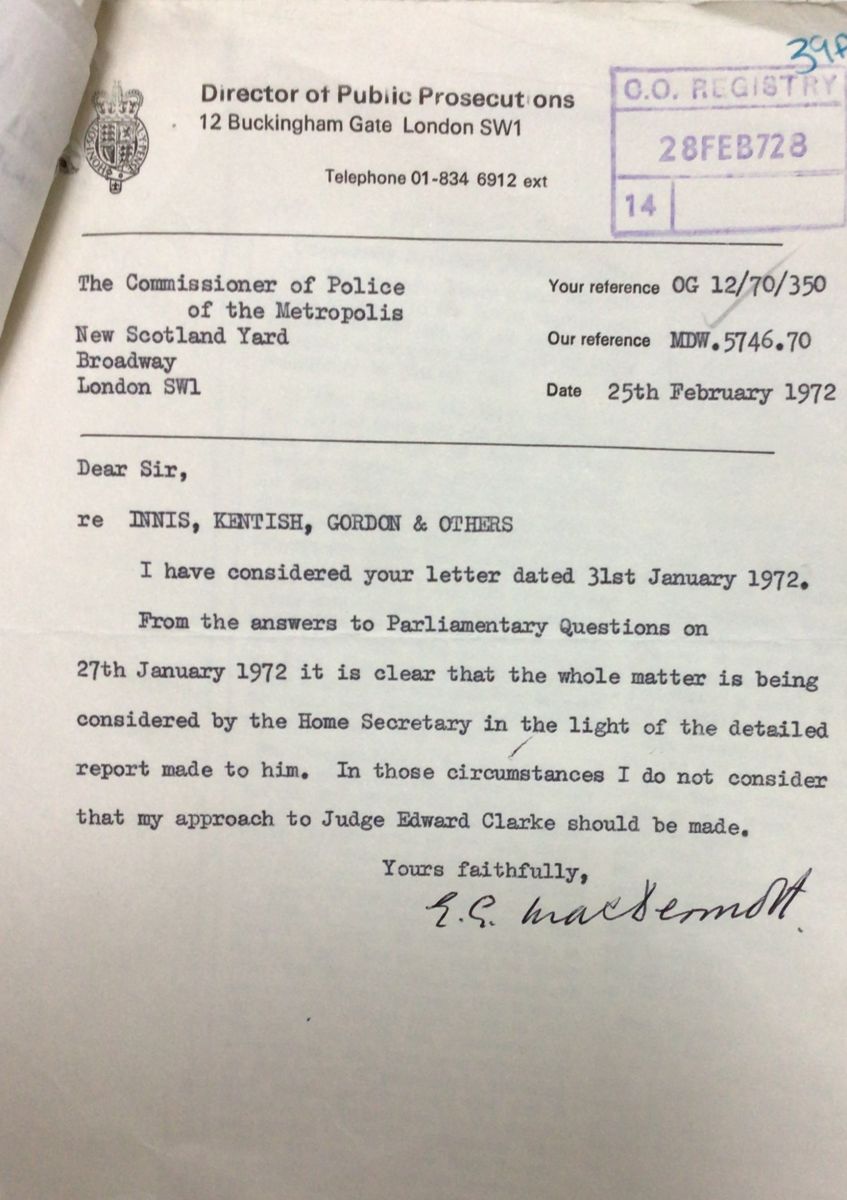

The DPP refused, ostensibly because the Home Secretary was looking into it, but one would hope that also because there was unease at a member of the executive branch interfering with the work of the judiciary (see Figure 2). The police kept an eye on events in parliament, and the official file includes a copy of the House of Commons exchange on the matter between the Home Secretary and MPs. In the end, though, nothing came of it: Clarke’s statement was never withdrawn.

Figure 2: Letter from to DPP to Commissioner, 25 February 1972 (MEPO 31/20)

Despite some improvements, 28 years later another judge would reach the same conclusion following The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry that there was ‘institutional racism’ in the Met. (Macpherson,1999) Further positive change has been made since then but it remains a work in progress.

The Mangrove Nine trial occupies an important place in the history of anti-racism in Britain. It challenges perceptions of an impartial criminal justice system and shows the defendants, not as passive recipients of justice, but as agents in their successful fight against unfair treatment.

References

Macdonald, I. (1977) ‘Up Against the Lawyers’, in Field, P., Bunce, R., Hassan, L. and Peacock, M. (eds.) (2019) Here to Stay, Here to Fight: A ‘Race Today’ Anthology. London: Pluto Press, pp. 154-7.

Macpherson, W. (1999) Report of the Steven Lawrence Inquiry. (Cm 4262-I). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/277111/4262.pdf (Accessed: 28 September 2021).

Mangrove Nine (1973) Directed by F. Rosso. [Feature film]. London: George Padmore Institute.

Material in The National Archives is reproduced by permission of the Metropolitan Police Authority on behalf of the Crown.

Andrew Gilbert

Andrew Gilbert

Dr Andrew Gilbert, is a Senior Lecturer in Law at The Open University