You are here

- Home

- Research Projects

- Completed Research Projects

- Contemporary Indian Literature

- Workshops

- Contemporary Indian Literature, Workshop, Presentation 2

Contemporary Indian Literature, Workshop, Presentation 2

Presentation by Professor Tapan Basu at the London Workshop

CONTEMPORARY INDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH: IS THERE A MARKET IN INDIA FOR THIS TEXT?

......It now appears that a niche has been created in India for Indian writing in English... a niche that is unrelated to Anglophone Western markets. This project tracks this change by gathering empirical data and undertakes analysis of the data in terms of concepts of Postcolonial Literature and World Literature.(1)

My paper has been titled in the interrogative mode so as to accommodate expressions of scepticism about the main assumption of our research project (stated above) that were voiced intermittently, but insistently, during the course of our (the members of the research team’s) interactions with key players in the field of our investigation. over the last eight months or so. For instance, at the workshop in New Delhi in March this year (2), a punctuation mark in our investigations, resource persons as diverse as Mr. Ravi Singh, Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Penguin Books in India, and Mr. Ajit Vikram Singh, Chief-Executive-Officer and Proprieter of the Fact and Fiction Bookshop in Vasant Vihar, New Delhi, while conceding a growth in the market for Indian writing in English in India in recent years, contested that the growth has been, in any way, significant, given especially the parallel and phenomenal growth in the Indian economy in general and the sales profiles of various kinds of consumer commodities in particular.

Notwithstanding these voices of doubt, we, the project researchers, abide by our contention that a market has developed indeed in India for Indian writing in English on a dimension and proportion in which such a market never existed in our country prior to the mid-1980s. Whether or not such a market has been exploited adequately on the supply side, on the demand side there is no gainsaying that such a market is craving for consummation. This position has been, more or less, affirmed by the two studies of the English language book-industry in India conducted in recent years, both from the trade point of view, one by the Khullar Management and Financial Investment Services in 1999 and the other by the British Council in 2003. Ours is, as far as we are aware, the first look at the domain from an academic point of view.

My presentation today will be divided into three parts. On the first part, I shall look at the emergence of a potential market for Indian writing in English in India in terms of its economic, social and cultural determinants. The contours of the actual market for Indian writing in English however are not as easily to be mapped as the contours of the potential market for Indian writing in English because of the lack of any officially authenticated data about production / distribution / retailing of different categories of books, such as are made available by agencies inside as well as outside the book industry in several other countries. Nevertheless, in the second part of my paper, I shall try and trace the shape of things as they exist in the arena of selling and buying of Indian writing in English in India, largely through a deductive analysis of subjective observations on the state of the indigenous English language book industry. The third and final part of my presentation will inquire into the gap between the actual market and the potential market for Indian writing in English in India, and remark upon the coordinates that need to be tightened if the possible is to be translated into the palpable.

I

At the base of a boom in the potential market for books in India, books in all Indian languages included, is an ambiance of material prosperity deriving from unprecedented economic growth over the last one-and-a half decades, increase in both National and Per Capita incomes, a rise in consumer confidence, and an expansion of the middle class constituency of likely customers for books.

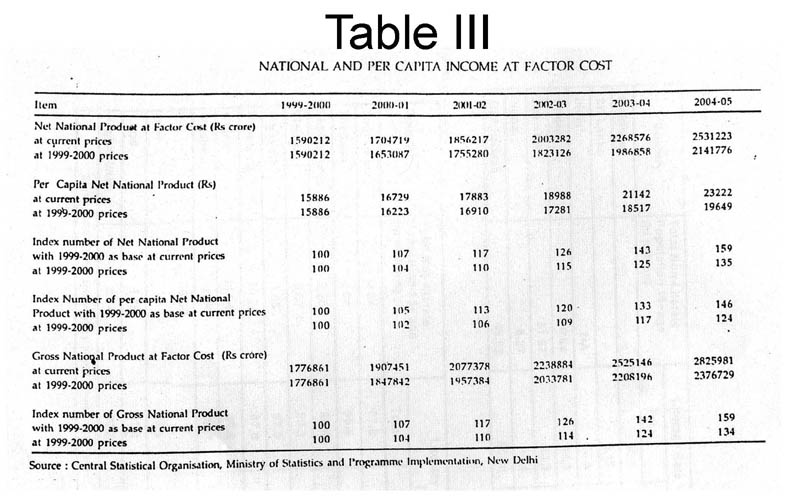

The overall economic growth in year 2006-2007, according to the Annual Budget presented by the Government of India earlier this year, has been close to 8%, the culmination of a steady climb in the growth rate through the 1990s. Through the 1990s, the Per Capita and National Income statistics registered a similar upsurge (see Table I, II, III)(3).

Tables 1 & 2:

Table 3:

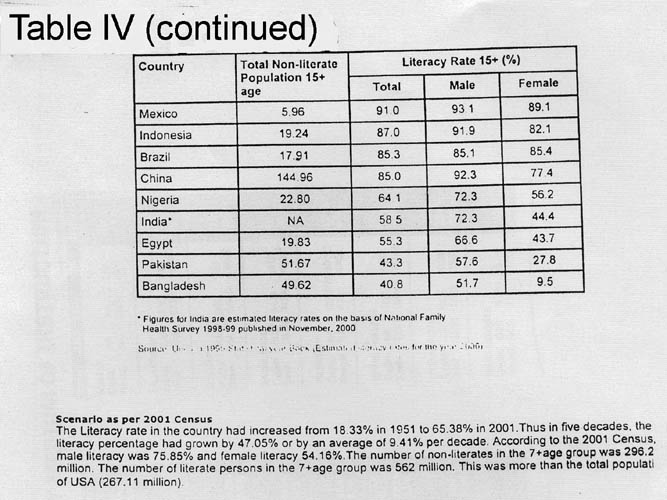

The percentage of literate persons (defined as anyone seven and above who can read and write in any language) has been also appreciating steadily, as successive census enumerations undertaken by the Indian government between 1951 and 2001 testify. The decade ending 2001, demarcated by Census 2001 on the one hand and Census 1991 on the other hand, in fact witnessed the most striking boost in literacy, with the total percentage of literate people peaking from 52.21 in 1991 to 64.84 in 2001 (see Table IV)(4). The aspiration for learning was obviously a direct fall-out of the sense of well-being on the economic terrain; it stemmed from faith in an India poised to realise itself as a global player, that extended beyond the limits of the primary metropolitan middle-class subjects of this feel-good vision.

Table 4:

The ideology of globalisation as opportunity, for empowerment as much as for employment, is now a hegemonic one, prompting people in small towns as much as in big cities of India to invest in its premises and its promises. An important requisite for worldly success from the globalisation ideology prism is the acquisition of functional skills –– speaking, reading, writing –– in the English language. Thus, literacy in English has become much in demand in almost every region in India.

An article recently published in The Times of India (as recently as March 25, 2007) succinctly represents this trend:

..... as more and more Indians wake up to the opportunities open to the English-speaking, state governments are finally picking up the grammar of what people want. Here’s how : in virtually every state in the country, English is being introduced earlier in regional language schools –– a sure sign that the queen’s lingo has more takers than ever before, cutting across linguistic and geographical barriers.(5)

The article cites an essay entitled, “Is English the Language of India’s Future?“ by Delhi-based socio-linguist Peggy Mohan, in which Mohan argues that the control of the discourse of science and technology, rather than it being the medium of great literature, is what accounts for the ascendancy of the English language in India. She says there is a transformation happening even among those not exposed to English world; Hindi words are being substituted by English words, the English chunks then getting larger, until the Hindi structure is dispensed with. ”Somehow en route something that is basically Hindi is changing into something that is basically English.”(6)

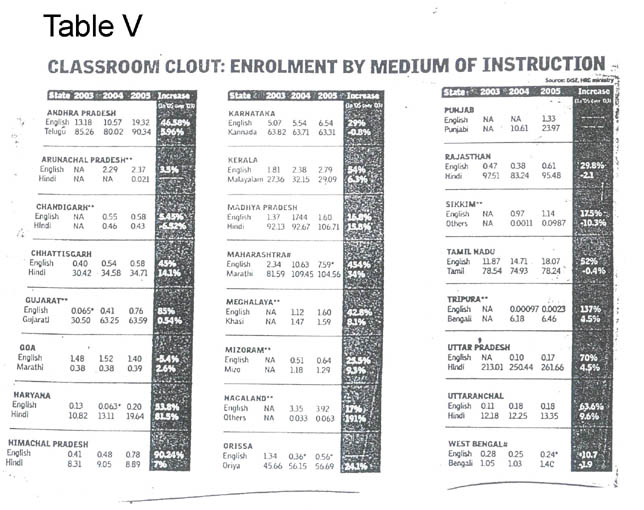

Mohan’s thesis is indubitably overstated. Statistics show that English is still not the highest scoring medium of instruction; some states do not even have a count of the number of students enrolled in schools in which the medium of instruction is English. But data from the District Information System for Education (DISE) of the Human Resources Development Ministry of the Government of India suggests that the lag may be narrowing. Most states have witnessed a dramatic inflation in the enrollment of students for instruction in the English medium as against regional medium instruction, propelling many states (like Maharashtra) to decide in favour of starting more English medium schools rather than schools in the regional medium (See Table V).(7)

The English language readership in India however does not tally in absolute measure with this trend. In absolute measure, as per the readership figures issued by the Indian Readership Survey 2006,The Times of India, with an estimate readership of 7.08 million in 2005, remains the sole English language newspaper among the list of top ten newspapers subscribed to by readers of newspapers. It trails behind newspapers in other languages, such as Dainik Jagran, Dainik Bhaskar, Daily Thanti, Amar Ujala, Malayala Manorama, Hindustan, Lokmat, Eenadu and Mathrubhumi(8). Vis-a-vis magazines, Saras Sahil, Kungumam and Vanitha, magazines in other languages, lead India Today in the English language. The English language India Today, with an estimate readership of 3.51 million on 2005, is the lone English magazine, to make it to the list of top ten magazines subscribed to by readers of magazines, as per the readership figures issued by the Indian Readership Survey 2006.(9)

Yet despite a decline in subscription to several magazines and newspapers in English, registered in the Indian Readership Survey 2006, English periodical literature, including these two genres, continues to thrive. In an interview on “The English Language Press : Growing Daily,” Chitralekha Basu, Deputy Features Editor of The Statesman, the oldest surviving daily in the English language in India, expounds upon the special position occupied by the English language press in India.

There are no less than 8141 English language periodicals published in India, according to a recent survey published in the anniversary issue of Outlook(August / September, 2005)! So you can imagine the variety in terms of design, get-up, political leanings and packaging strategies, even if tabloidisation of the mainstream papers seems to be a growing trend...

The smaller papers are read locally, but the big players like The Times of India, Hindustan Times, Indian Express, The Statesman, The Hindu have editions coming out from multiple cities and thus are read quite widely. Magazines like India Today and Outlook also have a nation-wide circulation, as do film magazines.

The readership is as varied as the papers themselves. Anybody who can read English will tend to read English language newspapers. English is one among the roughly 20 official languages spoken in India. It binds Indian people together because, unlike Hindi or Tamil, it is not regional. English is an international language –– one that is indelibly associated with aspirations, dreams, class, respectability and a sense of achievement in the Indian psyche, irrespective of one’s social-cultural background.(10)

The drop in subscription to periodical literature (including dailies, weeklies, fortnightlies, monthlies, quarterlies, half-yearlies and annuals) in the English language thus might be attributed to reasons extraneous to the popularity of English periodical literature in itself –– the spread of satellite television, easier internet access, doorstep photocopying facilities and expanding library networks.

None of these reasons have been a deterrant to the augmentation of the reading habit among Indians. The National Readership Survey 2005 posited that the time spent on reading by people in India had gone up quite significantly –– from 30 minutes per day to an average of 39 minutes per day over the previous three years. The increase was sharp in urban India (from 32 to 42 minutes per day) as well as in rural India (from 27 to 35 minutes per day). (11)

Clearly then, there is a potential market, more enormous than ever before, for every kind of writing –– Indian writing in English too –– at this historical moment in India. To what extent the actual market for Indian writing in English in India matches its potential market is a query that demands further investigation.

II

The year 2006-2007 has been an exciting year for the Indian book Industry as a whole : India was the “Guest of Honour” country at the Paris International Book Fair which was held from March 23 to 29, 2007. From October 4 to 8, 2006, at the Annual Frankfurt Book Fair, India was again the “Guest of Honour” country selected from a choice of 110 countries. With this, India became the only nation to be accorded this honour twice since the setting up of the Annual Book Fair at Frankfurt 59 years ago, already having won this distinction in 1986.

But the international focus on books from India, such as on these occasions, unfortunately very, very often translates into attention on writings published anywhere by persons of Indian origin (whether based abroad or home based), and not necessarily those Indians who publish their writings from India alone (those who are the focus of our research project). Hence the Indian writers invited to the Frankfurt Book Fair 2006 included an unwarranted number of writers in English, non-resident Indians as well as Indian residents. Commenting on the presence of Indian writers at the fair, Arun Sankar Chowdhury observes.

...Indian writing in English dominated the scene, perhaps more so than in 1986, though German publishing houses were sincerely convinced that they had made a brave effort to correct this imbalance by publishing translations of a dozen or more Indian authors writing in the regional languages. Nevertheless, the German literary supplements were perforce full of Kiran Nagarkar, Vikram Chandra and co., the question being one of linguistic and normative, and not necessarily literary access. Even if Kiran Desai got her Man-Booker only after the Fair, Shashi Tharoor himself was present at Frankfurt with his plan ‘B’, as he called it, after having failed with his candidature for the Secretary - Generalship of the United Nations. Arundhati Roy, the darling of the German reading public so far as Indian literature is concerned, was conspicuous by her absence, but Amit Chaudhuri and Amitav Ghosh, both familiar names in Germany, put in an appearance. (12)

Rather unkindly, Chowdhury interprets the charm of Indian writing in English for Western readers to this writing being “comprehensible as well as consumable... It is the West’s take-away, Balti(bucket) version of Indian literature.”(13) Even if such harsh slighting of all Indian writing of English is dismissed as misleading, it cannot be denied that an influential school of criticism of Indian writing in English, operating in India with as much blissful ignorance as in the West, tends to see Indian writing in English as the epitome of the best that has been expressed in the entire corpus of writings from India.(14)

Given the reach of this attitude of Anglocentric indifference to excellence in writings in Indian languages other than English, it is little wonder that writings in the regional languages of India encountered a “tough sell” at Frankfurt.(15) “Indian literature is still largely seen as the literature of authors who write in English. Regional literature hardly makes a dent in the West’s consciousness even though it is such a diverse scene”, said Peter Ripkin, head of the Frankfurt-based Society for the Promotion of Asian, African and Latin American literature.(16)

The marginalisation of Indian writings in the regional languages in the Western market, no matter how efficiently vended, is in counterpoise to the Indian market’s acknowledgment of the centrality of writings in the regional languages of India in the collective aggregate called Indian writing. Writings in the regional languages of India prosper apace in the Indian market along with Indian writing in English. The latter certainly is not in bloom to the exclusion of the former.

So what is the relative territory within the Indian market of the two categories of writings from India – regional language writing and English language writing? The English language segment comprises merely about 20% of the books in the market.(17)

If this seems meagre, it must be remembered that the percentage of the Indian population literate in English is just more than 7%. But 7% of the Indian population accounts for nearly 65 million persons knowing English, second only to the 215 million English-knowing persons in the United States of America and ahead of the gross population of Britain (about 60 million) and Australia (about 20 million)(18). A gigantic clientele of might-be readers of English books within India makes India an emerging market that is, to use the words of David Davidar, former publisher of Penguin India and currently publisher of Penguin Canada,

... the fastest growing English language market in the world today.

... the Indian market could be bigger than Canada and Australia in the next 10-15 years. (19)

The response to this beckoning trade zone on the part of English language publishers in India has been encouraging. The 20% segment of Indian books in the English language works out to a rough and ready 20,000 - 25,000 books, making India the third ranking country in the publishing of English language books, following the United States of America (inhabited by the maximum concentration of persons knowing English) and the United Kingdom (the home of English, so to say). As a foil stands the Arab kingdoms which together publish fewer than 8,000 English language books, a tiny 1% of the world’s sum.(20)

The English language books published in India predictably belong to a variety of classifications. Textbooks overwhelm the rest, a testimony to the colossal education geography of India encompassing 336 universities, of them 20 funded by the Union Government and 100 by private sources, 5589 colleges, 1,16,820 high schools, 1,98,094 middle schools, 6,41,695 primary schools plus lakhs of coaching / tuition institutes that have never been enumerated. Apart from textbooks, and aligned to their role, are the reference books, encylopaedias, atlases and dictionaries. A major share revolves around books propagating self-help, new age, spiritual, religious philosophies. Children’s books are an upcoming group. And bringing up the rear, anti-climactically, are the books in the English language that we like to call Indian literature in English.(21)

If publishers are running head over heels to sign up Indian writing in English, Indian writing in English that they are signing up is not always ‘literary’ writing in the narrow sense. As fallacious as the impression that Indian writing has little of worth except as Indian writing in English, is the impresion that Indian writing in English has little of worth except as Indian literature in English. The fallacy can be nailed by even a cursory perusal of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s classic, An Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English (2003), in which Mehrotra pries open the Indian literature in English canon by accommodating within this rubric, translations of regional writings into English, nature treatises, dissertations on literature and art, political essays and tracts on social issues. In the original plan for the History, he tells us in his “Editors Preface”, Mehrotra envisaged two more chapters, namely, “The Historian As Author” and “The Pulp Artists,” covering historical writings and writings of a journalistic sort respectively.(22)

The happy hunting ground that India is now becoming for publishers, both foreign and native, of English language books, is the habitat of writers in the English language who try their talent in one or many of the types of pencraft mentioned above. With English language writers of Indian origin winning international laurels and mopping up prizes such as the Commonwealth, the Pulitzer and the Booker for excellence in writing in the English language, every English-knowing Indian appears to be an eligible writer as much as s/he definitely is an eligible reader. Tempted to tap this fortuitous conjuncture of resources, as well as a trans-continental cultural climate in which India is in vogue, English language publishers have steadily established shop on Indian soil since the mid-1980s, not a few of these aiming to be the midwife to ‘the great Indian novel.’ The first of these publishers was Penguin India, a joint venture between Penguin Books and the Ananda Bazar Patrika, inaugurated in 1986. The launch was followed soon by Ravi Dayal Publishers. Harper Collins Publisher arrived five years later as the result of a tie-up between Harper Collins and Rupa Publishing House, a contract which dissolved after Rupa Publishing House and Harper Collins decided to sunder their agreement.

Not that any of these firms can claim credit for releasing any Indian novel in the English language that remotely measures up to international bestseller standards. But dreams die hard, and attempts to manufacture Indian bestsellers have been a key motif-force in the operation of English language publishers in India since the mid - 1980s.

In all this hype around English language novels from India, of the 1980s and the post - 1980s, it ought not to be forgotten that Indian writing in English has a past that pre-dates the 1980s and that English language publishers in India were requisitioning manuscripts from the 1940s onwards. In his contribution to the brochure on 60 years of Book Publishing in India, 1947-2007, prepared by the Federation of Indian Publishers in coincidence with the Frankfurt Book Fair 2006, Tejeshwar Singh charts out the career of publishing in the English language in India.(23)

In 1943, Asia Publishing House pioneered this engagement, publishing 250 titles annually and giving voice to many Indian writers, before succumbing to some financially debilitating errors of business by the end of the 1960s. Prior to that, British houses such as Oxford University Press, Macmillan, Blackie and Sons, and Longman, Green and Sons had been busy peddling their books, textbooks specifically, in the Indian market, the only Indian competition in this respect coming from S. Chand & Co.

Soon after 1947, three paperbacks publishers came into existence – Orient Paperbacks, India Book House and Jaico Books. While India Book House floated the Amar Chitra Katha series of comics on Indian themes in the English language, Jaico Books and Orient Paperbacks concentrated on the publication of English language books by Indian writers as well as books translated into English from the regional languages of India.

Some eminent names in academic publishing –– Popular Prakashan, P.C. Manaktala and Sons, People’s Publishing House, B.I. Publications, Munshiram Manoharlal and Motilal Banarsidas –– spawned during this era, although the textbook business endured, more or less, with publishers from Britain.

The monopoly of the British publishers in the textbook business was severely curtailed, from the 1960s, with the setting up of the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) and the State Councils of Educational Research and Training (SCERTs) which were entrusted with the task of fashioning education policies geared to domestic exegencies. The result was, as Tejeshwar Singh has described it,

... the virtual nationalisation of school texts. Commercial publishers were left to publish only supplementary readers, workbooks, and textbooks in a few subjects in which enrolments were not high.(24)

A few of the British publishers continued to survive in the field of textbooks by virtue of their long association with it. Among the successful Indian publishers of school texts were Frank Brothers, Navneet, Ratna Sagar and Madhuban Books.

An offshoot of the Cold War was the aggressive wooing of the Indian market for textbooks by book dealers from both the U.S.A and U.S.S.R., each vying to outdo the other by subsidising their textbooks for the market in India. Inevitably, governmental agencies on either end were responsible for the programmes of subsidisation of textbooks, after suitable English edition of these textbooks had been manufactured.

Almost as a reaction against the continued invasion of the Indian market from outside, the 1990s ushered in a phase of fierce protectionism. Buttressing the protectionist impulse was the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, a Government of India legislation of 1971, which stipulated that a foreign corporation transacting its affairs in India had to be owned to a minimum ratio of 60 percent by Indian promoters. This legislation led to the exodus of several foreign publishing firms from India and the initiation of partnerships between Indian and foreign firms as in Tata-McGraw Hill, Wiley Eastern, Prentice Hall of India and Affiliated East-West Press. By the 1980s, foreign firms had adjusted themselves to the changed circumstances, and the best of them, Penguin Books and Harper Collins Publisher being the examples already mentioned, had learned to ride comfortable piggyback on Indian partners in order to operate in India.

The 1980s moreover witnessed the birth of the small investment, independent of big money, Indian publishers in the English language – a Ravi Dayal Publishers, a Roli Books, a Manohar Publishers, a Kali for Women (now split into Zubaan and Women Unlimited) a Tulika, a Stree, an Academic Foundation, a Narosa, a Social Science Press and a Permanent Black, for instance.

But a turning of the tide in the 1990s, thanks to “the return of the multinational”, as Tejeshwar Singh desinates it,(25) threatens the mushrooming genesis of independent publishing initiatives. The trajectory of economic liberalisation, dictated by the Government of India, spelt the demise of the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act and its substitution by the Foreign Exchange Management Act, through which corporate giants with transnational stakes could delve into most sectors of the economy. In the 1990s, not surprisingly, Cambridge University Press, Pearson Education, Scholastic, Butterworths, Routledge, Random House and Picador tested the waters of the Indian market for English language books, each negotiating the market in India on its own muscle sans alliances with local entrepreneurs. Simultaneously, alliances forged previously were sundered, with local entrepreneurs persuaded into surrendering their shares to their collaborators from abroad.

III

The grand narrative of publishing of English language books for the Indian market would not be complete unless it is underscored these books are marketed in more than 80 countries. The irony is that while this is so, the actual market in India itself still lags behind the potential market.

K.S. Padmanabhan, Managing Director of East West Books (Chennai), highlights the hiatus between the potential market and the actual market, of course with special reference to the market for novels, thus:

The reported sale of 30,000 copies of Arundhuti Roy’s The God of Small Things, six months after its publication by India Ink, is a remarkable record for the Indian trade. It seems to indicate a sizeable market for the Indian English novels in the country. If this is so, why is it that other books in this genre (with the notable exceptions of those by Vikram Seth and Shobha De) have not sold that well?(26)

Informed guesstimates from within the trade hazard 10,000 as the benchmark for an average bestseller in the Indian market, while a midlist book is counted as lucky if between 2000 and 3000 copies of it are picked up. (The reliance on guesstimates, though unfortunate, is unavoidable, with booksellers, distributors and publishers in India alike avouching inability to draw upon authentic data in discussing the Indian market for books, on the simple, if specious, ground of non-maintainance of such data.

Both K.S. Padmanabhan and R. Sriram, ex-Managing Director of Crossword Bookstores Ltd., pointedly blame the supply side of the trade for proving unequal to the demand side. R. Sriram uses Chris Anderson’s recommendation of a “long tail” supply strategy of marketing (27) to interrogate the fallacy of insufficiency of demand drivers of the book trade in India. To quote Anderson, “Many of our assumptions of popular taste are no more than artefacts of poor supply and demand matching –– a market response to inefficient distribution.” (28) The distribution network for books in India, says Sriram, is as lacking as the network for the retailing of books (29). The book retailing network in India is spun around a maximum of 5000 outlets all over the country as against a minimum of 5 million outlets all over the country which compose the retailing network in India for mass consumer goods. Besides, the run-of-the-mill bookshop is very tiny, tinier than 1000 sq. ft. in size. And books, epitomising a long tail variety among commodities, in which the back list is as crucial as the front list, these shops cannot do justice to the galaxy of books in print. The distribution mechanism in India is likewise at the cottage industry stage, with little apparatus to manoeuvre around the long tail of books : the niche books customer is inexorably relegated to the background to the advantage of customers of mainstream books who are invariably foregrounded. The net result is a catering to the lowest common denominator of popular taste in books and a corresponding neglect of clientele for books which stray beyond the province of the usual.

The book market is also constrained by the affordibility factor. English language books in India are, in any case, more steeply priced than the books in the regional languages. In R. Sriram’s calculation, a mass-market regional language book normally costs Rs. 60.00, while a mass-market English language book normally costs Rs. 250.00. On the other hand, a movie ticket in a metropolis costs about Rs. 150.00 and in a provincial town about Rs. 75.00. As compared to movies, books therefore are expensive entertainment for a middle-class Indian pocket.(30)

An efficient public library system would help to circumvent the affordibility factor, but as K.S. Padmanabhan laments, “the public library system is far from satisfactory in our country as compared to those in other countries.”(31)

I began my paper by asking whether there is a market in India for contemporary Indian writing in English published from India. I end the paper by replying in the affirmative to my query, and with the qualification that the actual market for this body of texts awaits the event of its harmonisation with the potential market.

The moment of harmonisation will usher in a fresh chapter in the history of English literature with autonomous enclaves of production / circulation / consumption of English language texts developing in the erstwhile colonies of the Anglo-American world quite irrespective of the fate of the English language texts market on their home grounds. Shall we finally be able to travel beyond the perennial postcolonial moment in English Studies by banishing the bugbears of both an over-determining colonialism as well as its everlasting post-ness?

(1)Extracted from the prospectus to the research project on Contemporary Indian Literature in English and the Indian Market, sponsored by the Ferguson Centre for African and Asian Studies, the Open University, U.K.

(2)Workshop held under the aegis of the above-mentioned research project at the Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, from 8th to 10th March, 2007.

(3) Statistics culled out of Government of India documents, disseminated by the Publications Division of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting via India 2007: A Reference Annual.

(4) Statistics tabled by the National Literacy Mission of the Government of India on the website of the National Literacy Mission.

(5) Hemali Chhapia, “A is for Aspiration" The Times of India, March 25, 2007, p. 16.

(6) ibid

(7) Statistics tabled by District Information System for Education, Human Resource Development Ministry, Government of India; profferred as evidence in “A is for Aspiration” by Hemali Chhapia.

(8) “IRS 2006 : Dailies, Newspapers See Decline in Readership”, Newswatch India,

http://www.newswatch.in, April 9, 2006.

(9) ibid

(10) Chitralekha Basu, “The Indian English Press : Growing Daily “(An Interview), Anglow : A Review of the Anglophone World, anglow.net, April, 2007.

(11) “National Readership Survey (NRS) 2005 : Highlights”, Education in India, Allindiannewspapers.com,n.d.

(12) Arun Sankar Chowdhury, “Organising the Frankfurt Book Fair 2026,” DW-WORLD.DE, http://www2.dw-world.de/southasia/1.200773,1 html, October 19,2006.

(13) ibid

(14) The debate around the merits of Indian writing in the English language vis-a-vis writings in the regional languages of India is an old one, but it got a new lease of life in the wake of Salman Rushdie’s famous/infamous jibe in the “Introduction” to The Vintage Book of Indian Writing (London : Vintage, 1997), edited by himself and by Elizabeth West, denigrating “what has been produced in the 16 official languages of India, the so-called vernacular languages”, as inferior to the “stronger and more powerful body of work” belonging to “Indian writers working in English.” Rushdie’s pronouncement obviously met with indignant rejoinders as well as a counter-anthololgy which privileged regional language writings from India, namely, The Picador Book of Modern Indian Literature, (London : Picador, 2002), edited by Amit Chaudhuri.

(15) “India’s Regional Literature a Tough Sell at Frankfurt”, DW-WORLD.DE,

http://www2.dw-world.de/southasia/1.200773.1.htmb, October 6, 2006.

(16) ibid

(17) Dina N. Malhotra, “The Panorama of Indian Book Publishing”, 60 Years of Book Publishing in India : 1947-2007 (New Delhi : Federation of Indian Book Publishers, 2006), p.11.

(18) “India’s Growing Clout in English Language Publishing,” The Publishing Horizon,

http://prayatna.typepad.com/publishing/2007/01/indias-growing-html, January 1, 2007.

(19) ibid

(20) Abdullah Ali Madani, “Recognising India’s Huge Book Industry,“ gulfnews.com, April 8, 2007.

(21) Information gathered from Dina N. Malhotra, “The Panorama of Indian Book Publishing.” 60 Years of Book Publishing in India : 1947 – 2007 (New Delhi : Federation of Indian Book Publishers, 2006), p. 13.

(22) Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, “Editor’s Preface,” An Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English(New Delhi : Permanent Black, 2003), pp.xix-xxii.

(23) Tejeshwar Singh, “Publishing Scenario in Indian Languages : English,“ 60 Years of Book Publishing in India : 1947 - 2007, (New Delhi : Federation of Indian Book Publishers, 2006), pp. 49-58.

(24) ibid., p. 54.

(25) ibid., p. 57

(26) K.S. Padmanabhan, “Market for Novels from a Publisher’s Perspective,” The Book Industry in India : Context, Challenge and Strategy, ed. Sukumar Das (New Delhi: The Federation of Publishers’ and Booksellers’ Associations in India, 2004), p. 92.

(27) “The theory of the Long Tail is that our culture and economy is increasingly shifting away from a focus on a relatively small number of “hits”. (mainstream products and markets) at the head of the demand curve and toward a huge number of niches in the tail. As the costs of production and distribution fall, especially online, there is now less need to lump products and consumers into one-size-fits-all containers. In an era without the constraints of physical shelf space and other bottlenecks of distribution, narrowly-target goods and services can be as economically attractive as mainstream fare” (Chris Anderson, The Long Tail : A Public Diary on Themes around a Book, http://www.typepad.C, September 8, 2005.

(28) Quotation borrowed from presentation made by R. Sriram at the Jamia Millia Islamia workshop mentioned in note 2. Mr. Sriram’s presentation was entitled, “Understanding the Demand Drivers of Books in India.”

(29) R. Sriram, “Understanding the Demand Drivers of Books in India,” posted on website of research project on “Contemporary Indian Literature in English and the Indian Market,“ sponsored by the Ferguson Centre of African and Asian Studies, the Open University U.K.

(30) ibid

(31) K.S. Padmanabhan, “Market for Novels from a Publisher’s Perspective”, p. 93.

Books Consulted (Select)

Khullar Management and Financial Investment Services, Indian Book Publishing. New Delhi. U.S. Foreign Commercial Service and U.S. Department of State, 1999.

Rob Francis, Publishing Market Profile: India. New Delhi : The British Council, 2003.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (ed), An Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English. New Delhi : Permanent Black, 2003.

Sukumar Das (ed). The Book Industry in India: Context, Challenge and Strategy, New Delhi : The Federation of Publishers’ and Booksellers’ Associations in India, 2003.

Dina N. Malhotra (ed.), 60 Years of Book Publishing in India: 1947-2007. New Delhi: Federation of Indian Publishers, 2006.

India 2007: A Reference Manual. New Delhi: Publications Divisions, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, 2007.

Websites Consulted ( Select)

Official Websites of the National Literacy Mission (NLM), the National Readership Survey (NRS), the Indian Readership Survey (IRS), Newswatch India and The Publishing Horizon