You are here

- Home

- Publications

- Critical Essays

- Lorna Hardwick: Greek Drama at the end of the Twentieth century: Cultural Renaissance or Performative outrage?

Lorna Hardwick: Greek Drama at the end of the Twentieth century: Cultural Renaissance or Performative outrage?

This article is based on a lecture given to the annual meeting of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies in London in June 2000. It is offered here as a position paper to highlight aspects of current debate on performance and reception issues. I am grateful to the Council of the Society for their invitation and to members of the audience for comments and discussion, both on the day and subsequently.

‘Classics are simply residues, maps left over from earlier cultures; they invite you to make some sort of imaginative movement’: Jonathan Miller (1968), commenting on his work directing Robert Lowell’s Prometheus. [1]

My purpose in this lecture is to identify some of the imaginative movements which are taking place and to consider how they are being received and what kinds of cultural shift may be involved.

Introduction

The virtual explosion of performances of Greek plays, translations of Greek plays and adaptations of Greek plays shows no sign of diminishing. Within the last eighteen months or so in the UK alone we have had (the numbers in brackets refer to the documentation of the productions on the Data Base which is part of this research project) :

-

The London Festival of Greek Drama, an annual event, which this year had Birds in Greek (DB no. 2519), Oedipus the King in English translation and Peace in English translation (DB no. 877).

-

The triennial production in Greek at Bradfield College, this time a superb Hippolytus, notable both for its choreography for the Chorus based on modern music and dance rhythms and for its formal qualities (DB no. 2520).

-

The Actors of Dionysus tour with theAgamemnon (DB no. 1119) and Grave Gifts (DB no. 1113), the latter a bold decision to present the Choephori on its own.

-

The Oxford University Dramatic Society's Birds in translation (DB no. 967) and Iphigenia in Aulis in Greek (DB no. 966), as well as a production of Seamus Heaney’s A Cure at Troy (DB no. 1109), subtitled ‘after Sophocles’ and taking the Philoctetes as its source text.

-

Another student production of Birds - the Scottish Academy of Music and Drama’s version at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, entitled God Love Thatcher (fade to Greek)(DB no. 1108).

-

The Fringe also had a somewhat neglected Women of Troy by Courttia Newland, in which the opening words to the prologue were ‘ this is Nathan Poseidon reporting from the South Atlantic for the Times’ (DB no. 1114). (The Trojans were Christians and Cassandra a Jesus-freak).

-

Also at Edinburgh was the latest in the Tomee Theatre company’s series of Antigones, characterised by dance and the use of the body as the main instrument of communication (DB no. 1117)

-

Antigone also got prime time in Oxford and London in Declan Donellan’s version of Will Allan’s translation (DB no. 1091). This I found striking in its use of the movement of the Chorus to frame the changing focus of the action and in its ability to present Creon as a flawed tyrant from the beginning and yet to suggest in the second half of the play that the play is as much his tragedy as Antigone's.

-

In late 1998 we had the tour of the Craiova Theatre Company of Romania with their Oresteia (DB no. 940) directed by Silviu Purcarete. Four hours of Aeschylus in Romanian with English sur-titles looking like Tube-train indicator boards was not as dire as it sounds. The effect of silhouette and mime and the synchronised Chorus of grey suited politburo geriatrics was stunning and transcended language barriers, even for those in the audience who did not previously know the play.

-

The Oresteia, and especially the Eumenides, ought, one feels, to be the play for the turn of a century in such need of conflict resolution and the late Ted Hughes’version of the Oresteia, presented by the Royal National Theatre and directed by Katie Mitchell, took over the Cottesloe on the South Bank in London before touring the States (DB nos 1111 and 1112). Mitchell defended the Balkanisation and other contemporary allusions in the staging as responses to current uncertainties –‘a lot of us feel morally thrown…and don’t know how to find our bearings morally and politically. To some extent the production was working that through’ (New York Times, May 7, 2000).

-

In such a context, Electra also seems a play of choice and was presented in Greek in Newcastle and London by the pupils of Newcastle High School (DB no. 2547).

-

The Compass Theatre Company’s production of Electra (DB no 989), featuring Jane Montgomery in the title role, alternately outraged and transfixed audiences nationally. (It also prompted the only audience row I have witnessed, when after the play the foyer at the Ustinov Studio in Bath was blocked by debaters angry about whether the recognition scene should have been played in such a brutal manner or with tenderness).

-

Theatre Cryptic’s Electra (Glasgow and on the Edinburgh fringe) exploited multi-media, to achieve both shock and, in the recognition scene, tenderness and subtlety (DB no. 1115).

-

No-one who saw Messing with Medea (by the now sadly defunct Orchard Theatre Company, DB no. 1000), which both toured and showcased at The Other Place in Stratford-upon-Avon, will readily forget the versatility of the two member cast and especially the gripping, silently enacted physical and emotional transformation of the Nurse of the Prologue into the figure of Medea, silhouetted against a plain white sail sheet. The audience of fidgeting school-students were stilled and hardly drew breath for the rest of the performance.

-

In the summer of 2000 Fiona Shaw, directed by Deborah Warner is playing Medea at the Abbey, Dublin (DB no. 2573), and is, according to one critic (Lyn Gardner, The Guardian, 10/6/00) ‘more sad than bad, infected with the bitter humour of the terminally despairing’.

-

Drawing out the irony and playing Medea with black humour was a characteristic of Liz Lochhead’s translation, which featured in what for me has been the outstanding theatrical experience of the last few months, Greeks performed by theatre babel in the Old Fruitmarket in Glasgow in March. This consisted of three separate versions of Greek plays, each running for about one and a quarter hours and specially commissioned from modern Scottish writers: - Oedipus by David Grieg (DB no. 2524); Electra by Tom McGrath (DB no. 2521) and Medea by Lochhead (DB no. 2510). The Old Fruitmarket is what the name implies - a traditional and unconverted ex covered- market venue with stark red brick walls, high and resonant roof, cobbles and flagstones underfoot. The atmosphere was electric on the Saturday night when all three plays were presented in sequence to a capacity audience.

-

Scotland’s ability to energise new forms of classical theatre was underlined in the Edinburgh Royal Lyceum Theatre’s production of Edwin Morgan’s translation into modern Scots of Racine’s Phèdre. In this Phaedra (DB no. 2525) Euripides, Seneca, and Racine were interleaved on a playing space formed from a huge shell shape (designed by Isla Shaw). This took over the stalls and was raised to the level of the grand circle (with safety net in place) while some of the audience sat on what would traditionally have been the stage, giving the effect of performance in the round.

-

To the list of such 'close relatives' of Greek drama one might add the Gate Theatre’s touring production of Peter Oswald’s Odyssey, (DB no. 1090), directed by Martin Wylde and Tony Harrison’s verse-film Prometheus (DB no. 946), still discoverable at some Arts cinemas.

Now this may sound like a bewildering array of Greek plays (including some which were not very Greek either in conception or performance). And in a sense it is, but from it some significant patterns emerge:-

Firstly, productions range across the whole spectrum of theatre: student drama, touring productions directed mainly at the school and college syllabus but attracting broader audiences; fringe and experimental productions; commercial theatre; international tours by prestigious companies; involvement of leading actors, writers and directors as an integral part of their oeuvre. Greek plays and Greek referents are a significant part of artistic creative activity. In this respect, they can be seen both as part of the transmission of ancient culture and as a springboard for artistic and intellectual intervention in staging and interpretation, with all that that entails for various forms of theatre and for critique of modern artistic forms and their social and political context. Greek drama is a catalyst.

Secondly, there is a corresponding variety in audiences and in audience knowledge about the source plays and source culture. Clearly Greek plays, both in the original and in translation are an important part of student experience of theatre (as audiences and as players). For many, Greek plays are the only or primary source of awareness of ancient culture. They may be the only experience of Greek drama ‘away from the page’ and changes and adaptations will shape or reshape the audience’s views about the ancient world. Impact on the audience’s cultural sensitivity, to both ancient and modern and to perceptions of links and differences between the two, can be considerable.

Thirdly, there is the question of which plays are selected for performance (and I leave aside for the moment the influence of the syllabus!). It is often said that the 1980s and 1990s have prioritised Greek plays that are also war plays – well, that covers most of them! Karelisa Hartigan has argued that this is the case for the 20th century as a whole, at least in the USA, where she considers that Greek drama in the commercial theatre was most prominent when the country was involved in war. [2] Certainly its true that the prominence of certain plays seems to be cyclic and perhaps relates to some extent to the possibilities for the production style to resonate with modern contexts. Yet this is not always straightforward. For example, while the Eumenides is significant as a play which explores ways of breaking the cycle of revenge and killing, it is actually quite difficult to situate away from the ancient context, especially in terms of the importance of Athena’s support for the primacy of male over female as part of the resolution of the conflict. Modern staging increasingly includes an additional stress on the perspective of Clytemnestra, either by recasting the story from her viewpoint (as in the recent production in the USA of Kelly Stuart’s Furious Blood, DB no. 2581) or by including Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis as a prelude or by miming the sacrifice of Iphigenia at the crucial point in the chorus of the Agamemnon. (This is not always a very effective counter-attack against the demonisation of Clytemnestra, at least in the recent RNT production I referred to just now).

In contrast, it is interesting that Birds is making a comeback. It seems to me to be a play which defies seriously reductionist staging – ie staging which concentrates on crude equivalences between ancient and modern or which beats an ideological drum. I do not know whether there are plans to stage Paul Muldoon’s recent version. [3] If so it will be worth seeing for the very reason that Muldoon’s script self-reflexively plays with and subverts attempts to anchor it tightly in any one modern socio-political context. Although there are puns and allusions, they remain just that.

This question of the selection of plays for performance is not just a matter of the external environment but also of the internal world of the theatre. It also relates, I think, to the impact of canonical productions and performances, against which practitioners measure themselves or against which they react. This sometimes makes for interesting paradoxes. For example, some may come to be considered ‘canonical productions’ theatrically because of their authority and influence, for instance Mnouchkine’s Les Atrides or the Shaw/Warner Electra and they may nevertheless have provoked fierce debate about staging, interpretation, acting style and so on. This seems to me to be thoroughly healthy.

As an optimist, the features I have identified suggest to me that we are about to see a new and more sophisticated phase in the staging of Greek drama, with greater emphasis on creativity within classical repertoire. In hoping this I am probably in a minority. I am struck by the extent to which some critics (and academics) are overdosing on apoplexy. Here are some recent examples:

1) The cultural argument

In Arion 1996 was published an iconoclastic article by Herbert Golder ‘Geek Tragedy? – or why I’d rather go to the movies’.[4] Golder voiced a deep disenchantment with almost all contemporary staging, partly because he thought the productions were flawed but mainly because they were contemporary in a way which, he felt, privileged modern resonances and acting styles over the Greek. His main assertion was that ‘the ephemeral must never be allowed to occlude the essential’. Of course, this encodes a particular view of the Classical Tradition, which is seen as a vehicle for transmission of an iconic conception of the plays, rather than as a strand in dialogic processes of reception and refiguration. Golder’s view entails a rejection of insights from other traditions such as Noh drama (which he categorised as ‘Nipponising’ at the hands of Mnouchkine).

2) The argument about authenticity versus commercialism

Of course Golder has been castigated by Oliver Taplin and others but aspects of his unease permeate a good deal of academic responses to contemporary staging. Robert Garland, who is preparing a book in this area, suggested in a recent electronic seminar organised by the Reception of Classical Texts Research Project that the ideal would be to commission joint translations by a philologist and a professional writer, as is done for productions in the ancient theatre of Syracuse. The translation is tested in the actors’ school and modified according to the demands of fluency and actability. This would be interesting as an action research project but Garland thinks that such a synthesis of talent and expertise is not generally viable . He said – ‘although classicists are often deeply disturbed by the latitude that translations take, particularly those that are staged, they are of course in no position to teach the contemporary theatre director his or her profession, especially when big bucks are concerned, which is where the heart of the problem lies’.

3) The too-close-for-comfort argument

This takes a number of forms but usually involves accusations of creating a new mythology or conflating ancient and modern experience and sufferings – for example in the critical review by Keith Miller in the Times Literary Supplement of Tony Harrison’s Prometheus - ‘There is an arrogant tendency to conflate all of the big themes of the past 100 years into one enormous supermyth’. [5]

These reactions , I suggest, encode a number of features. Firstly, they reveal a sense of cultural ownership which privileges some appropriating cultures over others and gives academics a special role in safeguarding the authenticity of transmission. In other words, it is claimed that theatre in relation to Greek plays must be of a certain kind. Some aspects of this seem to be related to a sense of a crisis in Classics (especially Greek) and one senses that ‘Who killed Homer?’ may shortly be succeeded by ‘Who killed Greek drama?’ Then there is what I call the Phrynichos syndrome. Herodotus tells us (Book 6.21.2) that the subject matter of The destruction of Miletos was too close to home. Phrynichos crossed the safety gap between theatre and ‘real life’ and between mythology and civic life. He narrowed the distance between tragedy and the audience’s overpowering troubles and was attacked for doing this. Perhaps that was why the Harrison film of Prometheus offended? Yet if the gap is too great, the force of tragedy is lost. The balance between the two extremes will be one of the concerns of the rest of this paper.

A Renaissance of Greek Drama?

The criticisms and anxieties which I have just summarised represent a move away from the sense of relief, almost gratitude which one used to sense amongst audiences and critics when discussing the revival of Greek plays. There was almost a feeling that we had to enjoy, appreciate and praise, if only to ensure that plays continued to be presented and that Greek drama (and by implication a toe-hold on Greek language) did not fade from view. So in one way it might be said that fierce aesthetic and cultural debate is a sign of confidence, that Greek drama is established with some security in the repertoire, that its importance is recognised and that the nature and quality of performances is important not only for transmission of Greek culture but also for the vitality and diversity of modern theatrical experience. Yet in another sense, as I’ve suggested, the debates betray fear: a fear of cultural exchange, of loss of control over the processes of cultural transmission and interpretation.

I have always tended to resist the application of the term Renaissance to the phenomenon of the recovery of Greek drama in all the various sectors of theatre and performance that I described earlier. I have doubts about the metaphor because, despite the best efforts of cultural historians, the term is so often used in the narrow and unproblematic sense of reviving the past or even, at worst, as part of the ‘Grand Narrative’ of the rise of Western civilisation, a view summarised recently as ‘a triumphalist account of Western achievement from the Greeks onwards in which the Renaissance is a link in the chain which includes the Reformation, the scientific revolution, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution and so on’. [6]

The author of that verdict on the Grand Narrative, Peter Burke, has published a revisionist assessment of the nature and scope of the Renaissance. The features which his account attributes to the Renaissance are a source for several aspects of the model which I wish to develop in order to describe and test the cultural impact of Greek drama today. Some aspects of Burke’s approach are surely uncontroversial : he defines a Renaissance as a movement rather than as an event or a period. He asserts that this movement involved innovation as well as renovation and that it was characterised by enthusiasm for antiquity and the revival, reception and transformation of the classical tradition. Burke also identifies a paradox which is important for my concerns. Although his Renaissance emphasised the way in which innovation and the recovery of antiquity went together (p 2), he notes a discontinuity in attitude between that time and contemporary culture, which prizes novelty and finds it difficult to respond to the sometimes difficult relationship between innovation and tradition. Most important of all for my purposes is Burke’s presentation of the Renaissance as ‘de-centred’, rather than as holding the centre-stage position which has traditionally been ascribed to it. He views the culture of Western Europe at that time as one culture among others, ‘co-existing and interacting with its neighbours, notably (in his case) Byzantium and Islam, both of which had their own ‘Renaissances’ of Greek and Roman antiquity’ (p 3).

This draws attention to the way in which antiquity can function as an agent and catalyst in the processes of cultural change and cultural exchange, being definitively ‘owned’ by none of its activators or receivers. Burke also emphasises the status of his Renaissance as a ‘half-alien’ culture – ‘the very idea of a movement to revive the culture of the distant past has become alien to us, since it contradicts ideas of progress or modernity still widely taken for granted despite many recent critiques. At the very least – since there are degrees of otherness- we should view the culture of the Renaissance as a half-alien culture, one which is not only distant but receding, becoming more alien every year’ (p 4). The term ‘half-alien’ seems to me to encapsulate the corresponding ambivalence in modern relationships with antiquity. Yet on the other side of the coin, ‘half-alien’ also implies half -domesticated (sc related to ‘our’ history, ‘our’ culture, even ‘our’ values). Anything that threatens that half domestication risks turning Greek culture into something totally alien, and thus threatening security in the definition of domesticated culture and values.

Other aspects of Burke’s model are valuable too. He emphasises that the concept of reception is more ambiguous than it sounds (p 6). In the nineteenth century, for instance, it often used to be assumed that reception was ‘ the complementary opposite of tradition’, that tradition was a process of handing over, reception was a process of receiving and it was assumed that what was received was what was handed over. Alternatively (and Burke locates this in his Renaissance as well as in the theory of the late twentieth century), the emphasis could be on the changes that occur in the process of transmission. Reception is seen as a form of production or as leading to production. New work may be created even by acts of rejection as well as by appropriation, assimilation, adaptation and other forms of reaction and response.

There is now, increasingly, sensitivity to the role of the processes of translation, whether verbal or, as I shall argue in the case of Greek drama, also performative in a way which draws also on non-verbal translational practices. And translation theory now recognises that translation is not necessarily a pale imitation but may be a work of art in its own right, in which both source and target languages are transformed. Burke points to the metaphor of ‘bricolage’, the making of something new out of fragments of an earlier construction. This is a metaphor adapted by Derek Walcott in his Nobel Lecture in which he refers to the creation of a new work from the shards of shattered epic from the past. [7] Burke relates this metaphor to that of ‘context’, a metaphor taken from weaving (p 9). Context is applied not just to the parts of the text preceding and following a given quotation but also to the cultural, social and political surroundings of a text, image or idea. So ‘receiving’ involves a creative adaptation for the new context. According to Burke, this involves a double movement (p 9) - the first is that of de-contextualisation, dislocation and appropriation; the second, that of re-contextualisation, relocation, refamiliarisation. Of course, in the metaphorical framework of the ‘half-alien’ this may involve various kinds of hybridisation. It also leaves open the question of the extent to which the source contexts and the forms embedded in them are transplanted into the new.

The final aspect of Burke’s model which I find particularly appropriate is that of diaspora, although his model requires significant adaptations in my context. Burke identifies four diasporas (p. 4) which had a shaping role in his Renaissance. He uses the term mainly to cover movement of people, although he also recognises the movement of texts and images:

The first was of Greeks who moved westwards from the beginning of the 15th century.

The second was the Italian diaspora of artists, humanists and merchants (to Lyons, Antwerp and other cities).

The third was German, especially printers but also artists (reached the area England to Poland).

The fourth was of Netherlanders, mainly painters and sculptors who were active in the Baltic countries.

I think the metaphor of diaspora is helpful not only as a feature of Renaissance but also as a commentary on the situation that the texts and images of antiquity are in today as part of the process of reception, regeneration, refiguration and further reception. However, the metaphor needs to be filled out and contextualised in a way which differs sharply from the approach of Burke, although his broader concept of diaspora as energising Renaissance still holds. In the modern context I would identify three kinds of diaspora as crucial in relation to Greek drama:

-

The displacement of classical texts from the centre of education, culture and institutions. This has been happening progressively since the nineteenth century (as Chris Stray’s study has demonstrated in detail. [8] This displacement has been accelerated by various economic and social factors. It also involves an element of intellectual and moral rejection because of the association of an (admittedly selectively appropriated) classicism with slave societies, imperialism, colonialism, fascism and class ideology. Ironically, some of these socio-political systems were enabling so far as the positive aspects of dispersal were concerned, for example, through the export of colonial systems of education (which nurtured the young Derek Walcott) or through stimulating the use of classical texts and images in a culture of encoded resistance (for instance in the GDR or in apartheid South Africa).

-

In conjunction with this there has been another kind of diaspora, a separation of classical texts and images from their association with particular dominant groups or with gender and class exclusions. As the cultural politics of appropriation have become better understood, there has developed an increased awareness among non-classicists and classicists alike that it is simplistic to equate classical values and cultural achievement with those groups who have appropriated and used classical culture as a sanction for their own position. This awareness means that the ancient texts and images are liberated to be refigured and reappropriated by other groups and it is here that all the elements associated with performance, both verbal and non-verbal, have a crucial role. The current concern with classical plays in post-devolution Scotland, for example, promises to produce a significant commentary in this area.

-

Thirdly, there has been a diaspora of individual artists, writers and directors. This takes a different form. A figure like Derek Walcott is multiply displaced – from African and European roots (because of his ancestry), by empire, and from his home island by education, poetry and politics. Classical texts and themes are interwoven with all aspects of the history of this displacement and in Walcott’s response to it. This is one reason he has engaged so creatively with Homer, another displaced text. Seamus Heaney is also in a sense displaced, from the North of Ireland to the South, the product of an education part Irish- part Ascendancy-orientated and it is his engagement with Sophocles’ Philoctetes in A Cure at Troy and with Aeschylus’ Agamemnon in ‘Mycenae Lookout’ which is his means of mapping a route through contested fields. In a slightly different way, Tony Harrison has been displaced through education from his working class origins and has used classical referents both to map the process and to refigure the relationship between classical culture and modern politics. Women writers, especially in the theatre, have not been central to classical translation and staging but even here Timberlake Wertenbaker, Deborah Warner and Sarah Kane have spoken powerfully from the periphery and moved it towards the centre. Among directors, Bertold Brecht, Andrei Serban and Silviu Purcarete in different ways spring from a theatrical and political diaspora and have refigured plays from the classical canon as aesthetic experiment and ideological critique.

Furthermore, all these aspects of diaspora affect the nature of the audience and audience response (whether one conceives of the audience as actual or ideal). At any given moment, members of an audience have views which may converge or diverge, individually and collectively, in respect of their response to the particular play, their sense of the play’s relationship to the Greek source or myth and the sense of the play’s relationship to their own cultural framework, including their sense of what is or is not ‘half-alien’. As Declan Donnellan recently put it, ‘theatrical meaning, more than in any other work of art is created by the observer as well as by the artist’. [9] So I want now to move on to consider some examples of the role of modern performance in the recovery, transmission, refreshment and refiguration of Greek drama and to ask questions about what is involved in the construction of theatrical meaning and how this interconnects with the cultural perspectives of the observer.

The Power of Performance

In recent years, the concept of performativity has become increasingly prominent in Theatre Studies and related disciplines. However, there is by no means an agreed theoretical base for the parameters of the concept and its realisation in mis-en-scène across genres and cultures. For my purposes I shall explore applications of the concept which emphasise the role of performance as ‘doing’, achieving, transforming and as having the power and authority which goes with those acts. This of course includes verbal acts – and here I invoke J.L.Austin’s distinction between constative and performative utterances. The former report, describe and propose: the latter do or enact by virtue of being uttered. [10] However, my interest is as much in the non-verbal languages of theatre as in the verbal. The performative impact of a performance is created not only by the spoken text/translation/acting script but also by the staging, set design, lighting, costume, music and choreography. Furthermore, performative aspects of culture are not confined to the theatre, dance studio or concert hall: anthropological study of ritual and sociological analysis of everyday life have revealed overlaps and interactions. In relation to the ancient world, recent studies have investigated the relationship between the Athenian democracy and performance culture and have emphasised the relationship between public performance of various kinds and broader issues relating to political agendas, the social function of language, the construction of the political subject and social stress and clashes of power. Critics have also emphasised the often transitional state in performance of tragedy in the fifth century, especially the redrawing of genre boundaries, the refinement of dialogue and the role of stage effects.[11] The response of modern performance to these aspects of ancient culture, both theatricially and, if I may use the term, archaeologically, transplants and refigures these issues into modern theatrical experience and with reference to modern cultural contexts. An example would be a modern performance’s sensitivity to nuances of performative mode when representing vendetta justice and forensic justice.

In his introduction, ‘Programme Notes’, to the recent edited collection of Essays on Performance Culture and Athenian Democracy, Simon Goldhill has identified a framework for investigation of the Athenian context of performance. [12]This is bounded by four crucial Greek terms: 1) agon (contest); 2) epideixis (display). Taken together these two require an audience. 3) schema – this is perhaps more problematic and has an even wider semantic field. It includes gesture, dress and equipment, the physical appearance which is subjected to the gaze of the citizens (and which can involve concealment or semblance). Schema involves positioning, of self or others. In Athens the schema was open to scrutiny, evaluation and regulation. Finally, Goldhill identifies 4) theoria, the term he uses to discuss the changing politics of spectacle and the various aspects of spectating, ranging from the act of attending and watching to some kind of participation (in the religious and civic ritual, or as a judge).

Considering the role of the spectator or in modern terms the audience, reviewers, critics and perhaps the Arts funders, raises significant questions about who ‘counts’ and of the relationship between individual, group and collective response and activity. It also raises issues about the relationship between the ‘audience’ both inside and outside the play (including the construction and performance of the Chorus). If performance is, as Goldhill suggests (p.1) ‘a useful heuristic category’ which can be used to explore the connections and overlaps between different areas of social, artistic and political activity and if these connections and overlaps are significant for understanding the culture of the Athenian democracy, it follows that their mediation and enactment in modern performance is equally (though differently) significant for understanding the cultures which contribute to and shape the performances and their critical reception. In this sense, the complaint of Colin Meir that Seamus Heaney is ‘creating a new mythology’ and the critical unease of Shaun Richards about the (mis)translation of Greek drama on the modern Irish stage look less like a plea for authenticity than an expression of unease about the potency of Greek drama in performance to expose faultlines and cracks in modern cultural and political consciousness. [13]

There is another reason, too, why the modern performative impact of Greek drama is problematic. This is because performance itself is ephemeral and its nature and impact cannot be captured in the same way as is attempted with written texts. Video may be useful but it is partial and mono-visual and cannot in any case recreate the interactive buzz of audience participation. Even the best efforts of current research projects to document the elements of performance have the limitations that the term implies. They may be able to map the contribution of the languages of gesture and movement, dance, music, stage effects, colour, costume and so on but they document an historical event not a present moment in which verbal and non-verbal combine to create the spectacle. What they can do, however, is to record something about the balance held in each production between the familiar and the ‘half-alien’, between the domestic applications and the ‘safety-gap’; that is they can suggest the nature and extent of the critical distance which was created for a particular audience at a particular time. I will mention just two recent examples where the interweaving of the languages of theatre produced a performance which both outraged some critics and transformed perceptions of the cultural scope of Greek drama. These are taken from the performances of Les Atrides by Le Théâtre du Soleil and a South African Medea. In each case I will select only one aspect for comment.

My first example illustrates aspects of an oriental approach to theatre, developed by the French-based company Le Théâtre du Soleil and their director Ariane Mnouchkine. Their performance of the Oresteia was preceded by Euripides’ Iphigenia at Aulis and entitled Les Atrides (DB no. 152). It toured internationally and was performed in the UK at Bradford in 1992.The company had a background in Eastern repertoire and the production drew on the music, movement, acting styles and costume of Europe, Africa, China, India, the Levant and Japan. The Japanese traditional theatres of Noh and Kabuki, like the Greeks, used male actors, masks, poetic language and heroic settings. My colleague Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones kindly suggested suitable slides and gave me his recollections of the performance. (Unfortunately for copyright reasons it is not possible to reproduce the Les Atrides slides here).

SLIDE 1

Kassandra, Trojan princess and prophetess of Apollo, dressed like a Noh priestess in a thickly padded kimono.

SLIDE 2

The three Furies, who in the Eumenides were dressed like oriental peasants in layered short dirty kimonos. This led some reviewers to compare them to modern bag ladies (Note the battered footware).

SLIDE 3

The performance’s approach to the audience covered the whole sequence of audience experiences. The audience was inducted into the cross-cultural aspects of its experience as soon as it entered the building (a large ware-house). One might compare Heiner Müller’s Medea Material, which also explicitly gave the audience a role as translators/interpreters. [14] For Les Atrides, the props in the Reception Hall included a huge map of the Mediterranean world showing the voyages of Agamemnon; displays relating to Greek life, including food and an entrance area in which the audience walked above a sequence of life size terracotta figures, like the Chinese terracotta army.

SLIDES 4 and 5

Then the audience was encouraged to talk to the performers as they applied their make-up and tied on their costumes. The lights dimmed and the dancers of the Chorus in red, black and yellow costumes, rushed on to the roar of the kettle drum.

SLIDE 6

In the staging, Mnouchkine adapted both Greek and Japanese conventions and used make-up masks which retained the capacity for a language of facial movement (rather than shifting the emphasis entirely to body movement). The formalised make-up here expressed grief and ritual lamentation.

SLIDES 7 and 8

In contrast, the male characters, wearing Kathakali heroic make-up (originating in seventeenth century epic story telling in India) weep ‘real’ tears. Here is Agamemnon, lamenting the sacrifice of his daughter

SLIDE 9

As Mnouchkine put it – ‘push internal feeling and external for to the limit’.

Referring back to the revisionist Renaissance model I considered earlier, you can see that Les Atrides involved a performative disruption of any easy association between revival of Greek drama and the concept of a Grand Narrative of Western culture and that in it renovation and innovation worked side by side. There is certainly a dynamic of diaspora, a displacement of some of the accretions to the Classical tradition and especially of the association of a canonical text with a particular dominant culture. The response of critics may be conditioned by the fact that for those accustomed to a western theatrical tradition, the performance then becomes more that ‘half-alien’ - hence the desire of Golder to reject it in favour of a gospel performance style that he considered was more familiar, more domestic, to the culture of the USA, and especially to its ritual and religious aspects.

My final example is from the Mark Fleischman and Jennie Reznek directed production of Medea performed in South Africa (Cape Town, Grahamstown and Johannesburg) in three seasons between October 1994 and March 1996 (DB no. 827). It was an adaptation of the story of Medea and Jason, drawing on Euripides, Seneca and Apollonius of Rhodes (Argonautica). The production encouraged the audience to make connections between Medea, the ‘marginalised barbarian’ and those population groups humiliated and disempowered by apartheid and between Jason and those who had violated human rights in their pursuit of power.

SLIDE 10: Medea

Scene from a South African adaptation of Euripides' Medea. Performed by Jazzart Dance Theatre during 1994-1996.

Directors: Mark Fleischman and Jennie Reznek

Photographer Ruphin Coudyzer.

Choreographer - Alfred Hinkel

Composer - Rene Avenant

Actor - Bo Petersen (Medea)

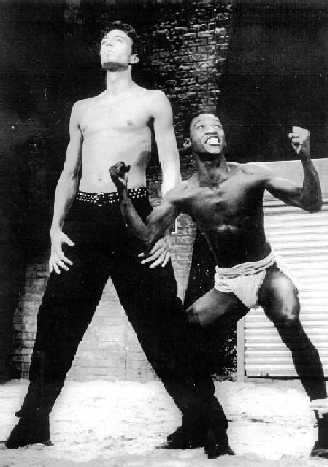

Slide 11: Jason and the Praise Singer

Scene from a South African adaptation of Euripides' Medea. Performed by Jazzart Dance Theatre during 1994-1996.

Directors: Mark Fleischman and Jennie Reznek

Photographer Ruphin Coudyzer.

Choreographer - Alfred Hinkel

Composer - Rene Avenant

The performance was a collaborative creation by a multi-racial cast of actors and dancers. The dancers who took the role of the Chorus were from Jazzart Dance Theatre, the first South African multi-racial modern dance company. Representation via the body has been a key performative strategy for post-colonial theatres.[15] There is a link to my previous example in that the Kathakali made-up actors’ stylised face expressions in Les Atrides also involve communication of carefully preserved systems of meaning through the actors’ bodies, but the body movement in the Jazzart approach, while drawing on traditional forms of expression also involved creative improvisation in the rehearsal sequence. Their principle is that the actor’s body is not just a vehicle for conveying meaning but can actually communicate nuances of the processes of struggle through movement, covering, revealing and even contortion and ‘fracture’.

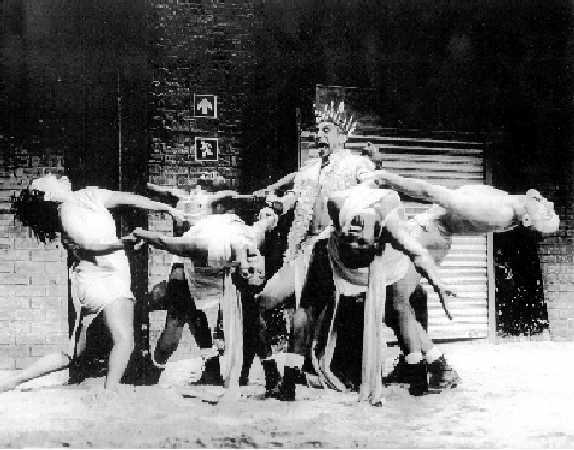

Incidentally, Jazzart was the group which reworked Gumboot dancing to generate a dance form to represent the ways in which repressed identities could be encoded through movement and thus could act as a way of empowering the otherwise repressed and silent (in that case the miners of South Africa). In Medea, dance was a way of incorporating oral tradition and consciousness into the play and thus also was a means of transcending language barriers. In a country where eleven languages have official status, verbal and somatic languages joined together to tell the story. The Chorus had a double role. In the Corinthian sequences they impersonated Greeks, using Western contemporary jazz dance. In the Colchis scenes, they were transformed into ethnic Colchians, wearing tribal dress with African dance movements.

SLIDE 12: Aeetes and the Colchian Chorus

Scene from a South African adaptation of Euripides' Medea. Performed by Jazzart Dance Theatre during 1994-1996.

Directors: Mark Fleischman and Jennie Reznek

Photographer Ruphin Coudyzer.

Choreographer - Alfred Hinkel

Composer - Rene Avenant

SLIDE 13: Aeetes and Medea

Scene from a South African adaptation of Euripides' Medea. Performed by Jazzart Dance Theatre during 1994-1996.

Directors: Mark Fleischman and Jennie Reznek

Photographer Ruphin Coudyzer.

Choreographer - Alfred Hinkel

Composer - Rene Avenant

In a recent article the late Margaret Mezzabotta (to whom I am indebted for these slides) described the effect on the audiences-

'Each of the linguistic visual and musical codes through which the performance communicated was interpreted with varying degrees of ease by the individual members of the audience depending on their cultural backgrounds. The spectators’ uneven comprehension of the play’s different signifying systems became a metaphor for the difficulty of understanding what was happening in South Africa in the immediate post-election period, during which old structures and certainties disappeared almost overnight to make way for a new set of givens, likewise subject to constant revision.' [16]

This comment seems to me to encapsulate many of the problems that are reflected in critical and academic reaction to the impact of performances and adaptations of Greek drama. [17] It is a commonplace to describe drama as a gateway to cultural dialogue - as Gershon Shaked has put it , ‘only the art of the theatre through its experience in translation on the stage can bring the distant near and reduce the dread [which] are not easily grasped and must be reinterpreted to bring them closer to their audience’.[18] However, it seems to me that while a good deal of attention has been paid to authors (ancient and modern), to directors and even to the role of academics (as advisors and cultural ‘gatekeepers’), the role of the spectators/ audience in this complex transaction has been under-examined. The audience, along with the modern translator/author and the director possesses powers to shape, interpret and also to mediate. Part of this power is cultural, part psychological, part economic (if no audience this time, then no Chorus next time). Of course, the audience is not undifferentiated. Nor is its hermeneutic competence unambiguous, though it may be transformed by or indeed itself transform the performance. What is ‘half-alien’ or maintains the ‘safety-gap’ for some is not so for others. Because audiences are now so diverse, both in terms of sub-cultures, as I indicated at the beginning, and so also in terms of cultural referents, the tightrope between the half-alien and the domestic, the safe critical distance and the uncomfortably challenging becomes more problematic, more wobbly, less predictable. Agon, epideixis, schema and theoria are subject to a scrutiny which, unlike that of the Athenian democracy, is both wider and narrower in its cultural awareness, less certain in the definitions, boundaries and applications of its discrimination between insiders and outsiders and sometimes less certain that such discrimination is either coherently justifiable or desirable.

Over and above this, audiences differ in their awareness and experience of the different aspects of the classical diasporas which I have discussed. So, too, do conceptions of what is or might be entailed in a Renaissance of Greek drama and in the limits and opportunities associated with performative innovation and transformation. Therefore, it seems to me that this particular Renaissance needs the ‘outrages’ in order that distinctive voices and representations of the constituent diasporas can be uttered, verbally and non-verbally. They help us to refocus our attention on the source texts, the performances and contexts of reception and on our own cultural assumptions about the alien, the half-alien and the ‘safety-gaps’.

Lorna Hardwick

December 2000

Endnotes

[1] Jonathan Miller, quoted in Jonathan Price, ‘Jonathan Miller directs Robert Lowell’s Prometheus’, Yale Theatre 1, Spring, 1968, 40

[2] Karelisa Hartigan, Greek Tragedy on the American Stage: Ancient Drama in the Commercial Theatre, 1882-1994, Westport CT, Greenwood Press 1995)

[3] Paul Muldoon, tr. with Richard Martin, The Birds, Oldcastle Co Meath, Gallery Books, 1999.

[4] Arion, third Series 4.1 Spring 1996 pp 174-209.

[5] Keith Miller, Times Literary Supplement, May 14 1999.

[6] Peter Burke, The European Renaissance, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 3.

[7] Derek Walcott, The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory, New York, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1993.

[8] C Stray, Classics Transformed:schools,universities and society In England 1830 – 1960, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1998.

[9] Source: Declan Donnellan, contribution to BBC/Open University video discussion of As You Like It.

[10] See for example J.L.Austin, How to do things with words, 2nd ed. 1975.

[11] See for example Helene Foley’s discussion in her Introduction to Peter Meineck’s translation of the Oresteia, Indianapolis, Hackett, 1998pxv.

[12] In (ed) Simon Goldhill, Essays on Performance Culture and Athenian Democracy, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

[13] For further discussion see Lorna Hardwick, Translating Words, Translating Cultures, London, Duckworth, 2000, ch 5.

[14] See n.13 Hardwick, 2000, ch 4.

[15] See eg H Gilbert and J Tompkins, Post-Colonial Drama, theory, practice, politics, London and New York, Routledge, 1996, chapter 5.

[16] M Mezzabotta , ‘Ancient Greek Drama in the New South Africa’ in (edd) L Hardwick, P E Easterling, S Ireland, F Macintosh and N Lowe, Selected Proceedings of the January Conference 1999: Theatre Ancient and Modern, Milton Keynes, 2000, 253. Also published electronically.

[17] For discussion of the cultural positioning of theatrical reviews see the critical essay by Lorna Hardwick, The Theatrical Review as a Primary Source on this Website.

[18] In (edd) H Scolnicov and P Holland, The Play out of Context: Transferring Plays from Culture to Culture, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989,10.