You are here

- Home

- Blog

- Can monitoring enhance my teaching practice? The latest scholarship research within The Open University suggests it can

Can monitoring enhance my teaching practice? The latest scholarship research within The Open University suggests it can

The UK Quality Code for Higher Education explicitly refers to the need for Assessment and feedback to be “purposeful and supports the learning process” (QAA, 2018).

Like many Higher Education Institutions, The Open University (OU) as part of its quality assurance (QA) processes use a process called Monitoring to review a sample of marked assessments and provides feedback to tutors on the gradings and feedback provided to students. This process provides many benefits to module teams, tutors and students. Module teams benefit from observing how assessments are interpreted and marked. Tutors receive peer feedback from their colleagues on their marking and their student feedback. Students also benefit from knowing their assessments are part of a thorough QA process.

Tutors in the OU are also referred to as Associate Lecturers (ALs), and they are managed by Student Experience Managers (SEMs) and Staff Tutors (STs).

Research methodology

A large-scale survey was undertaken with the use of an online questionnaire to all monitors (who provide peer feedback on marked assessments) and monitees (who receive feedback on their marked assessments). This survey was sent to all four Faculties of the University including Faculty of Business and Law (FBL), Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS), Faculty of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) and Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies (WELS). 248 monitors and monitees responded to the large-scale anonymous survey that explored the monitoring process, a 12% response rate. Of those 143 (58%) were monitees, 13 (5%) were monitors and 91 (37%) were both monitee and monitor.

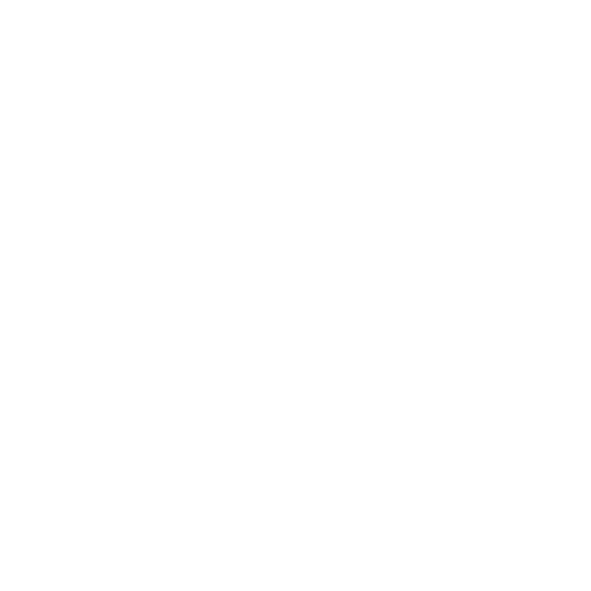

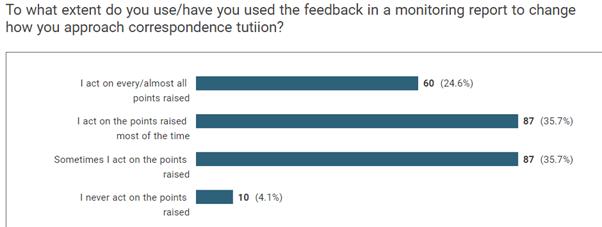

This pan-university scholarship project showed that monitoring has an impact on correspondence tuition and thus the student experience. 89% of the monitees who responded had read their monitoring reports carefully or extremely carefully and almost all (96%) said they acted on the points raised to some extent.

Some of the comments on the qualitative data included a monitee saying they had ‘incorporated suggestions around feeding forward for next assignment’. Another monitee had ‘given more praise’.

In addition, 94% of monitors surveyed stated they felt that the points they raised in the monitoring report were acted upon all or some of the time. One monitor said, ‘I have had ALs contact me and say they have changed their practice for the better following feedback.’ Another stated ‘One wonderful tutor responded…and we have had long discussions about how we mark and teach..’.

Whilst there are benefits to receiving the report it can also be daunting

It is clear from the research that monitors and monitees benefit from the process but receiving monitoring peer feedback can be a daunting experience for some; ‘Being assessed for performance by one's colleagues can be humiliating and engender bad feeling.’ said one monitee. This is reflected in the fact that 4% of monitees who responded did not read their monitoring reports at all.

There are two categories that the monitors can use in the monitoring report in relation to the grading awarded and the feedback provided: meets or exceeds requirements, or requires further exploration. Some monitors did not use both categories with 18.4% of respondents only using ‘meets or exceeds requirements’. One monitor commented: ‘I feel that the 'requires further exploration' category puts me in a position where I am criticising my colleague's work, so I don't use it.’

Ridge & Lavigne (2020:18) cited ‘collaboration among teachers as one of the major reported benefits of peer-to-peer feedback.’ This is further supported in the works of Jao, 2013; Koch, 2014; Phillips & Glickman, 1991; Pollara, 2012; and Porras, Diaz, & Nievens, 2018. Our research showed that these benefits are not being fully realised in the process, given that 4% of monitees do not read their feedback and 18% of monitors do not use both categories within their feedback.

What about the training provided?

Given the value and impact of monitoring, monitors must be trained appropriately for this role. Our research evaluated the OU monitoring training provision, and found that only 40% of monitors had completed this training. Worryingly 9% couldn’t remember if they had completed the training at all. Although 98% of those who had completed the training felt the training fully or somewhat equipped them for their monitor role. The lack of engagement with the monitoring training highlights a potential issue around the communication and recording of the training provided.

What if things don’t go well and there are disagreements?

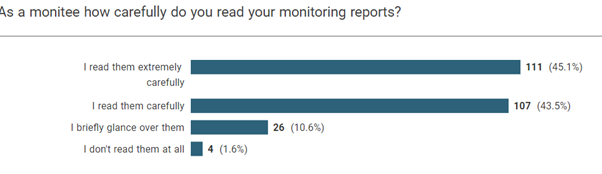

It is recognised that differences in opinion can exist in peer feedback processes. As highlighted by Ridge & Lavigne (2020:18) ‘considering the practice of peer feedback, we might consider that peers could possibly provide misleading or inaccurate feedback.’ Our own study found that nearly a quarter of tutors who disagreed with the monitoring report took no action at all.

Whilst 33% did in fact contact the monitor, 42% contacted their Student Experience Manager or Staff Tutor. This does present an opportunity to promote further dialogue between the monitor and the monitee. This is further supported by comments from monitors and monitees; ‘It would be good to have informal discussions about the monitoring process with other monitors and monitoring should be a dialogic process, encouraging collaborative discussion and feedback between ALs, monitors and line managers.’

Strong themes emerging from the research emphasised the importance of collaborative dialogue, mutual respect, and supportive discussions as key elements of the peer feedback process.

Call to action

Providing feedback on teaching and assessment practices is essential in Higher Education Institutions. Within The Open University peer monitoring is also an integral part of The Open University’s tuition model. What can Higher Education institutions, including the OU, do to encourage both monitors and monitees to engage fully with the process?

- Promote and encourage more monitors to complete the monitoring training or refresh their skills.

- Encourage more markers to take on roles as monitors to support their own development and those of their peers.

- Encourage all monitees to read and respond constructively and openly to their reports.

- Encourage dialogue between the monitor and the monitee.

For more details about the research please contact Allan.Mooney@open.ac.uk or Janette.walllace@open.ac.uk.

References

Jao, L. (2013). Peer coaching as a model for professional development in the elementary mathematics context: Challenges, needs and rewards. Policy Futures in Education, 11(3), 290– 297. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2013.11.3.290

Koch, M.-A. (2014, January 1). The relationship between peer coaching, collaboration and collegiality, teacher effectiveness and leadership (doctoral dissertation). Walden University

Monitoring Website (2024), Website: TMA Monitoring | learn3 (open.ac.uk) Accessed 150524

Nieland, S. (2020) Making the most of monitoring. http://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/FASSTEST/index.php/making-the-most-of-monitoring/ (accessed 11 June 2021)

Phillips, M. D., & Glickman, C. D. (1991). Peer coaching: Developmental approach to enhancing teacher thinking. Journal of Staff Development, 12(2), 20–25

Pike et al (2016). TMA Monitoring: Good practice and training. https://openuniv.sharepoint.com/sites/units/lds/scholarship-exchange/Lists/projects/DispForm.aspx?ID=312 (accessed 14 June 2021).

Ridge, B. L., & Lavigne, A. L. (2020). Improving instructional practice through peer observation and feedback: A review of the literature. Education Policy Analysis, P18 Archives, 28, 61. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.28.5023

Tatlow-Golden, M. (2020) E102 Monitoring Project, informal communication.

Allan Mooney

Allan loves tutoring and all things learning. He completed his MBA and MSC in HRM at Caledonian University, prior to which he held the post of Head of Learning and Development within Forestry and Land Scotland, an agency of the Scottish Government. Allan has also been a CIPD lecturer at City of Glasgow College and the Chair of the CIPD Organisational Development Group and is currently a Chartered Fellow of CIPD, Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and a Certified Management Business Educator.

Allan has worked at The Open University for 14 years and has previously been a student with the institution. He is currently a Senior Lecturer and Assistant Head of Student Experience, teaching on two modules in the Business School at level 2 and level 3.

Janette Wallace

Janette is passionate about learning and supporting students in their OU journey. She is a Senior Lecturer and Staff Tutor in the school of Life Health and Chemical Sciences (LHCS) and as part of this is Qualification Director for the OU’s taught postgraduate MSc. Mental Health Sciences programme and a Module Team Chair (Science project module). Janette is also an Associate Lecturer and enjoys building relationships with her students. She enjoys educational research and is involved in an Access Participation and Success (APS) funded project to explore and support students’ sense of belonging in LHCS.

Blog posts

- Rethinking Tuition: Reflections from the Staff Tutor / Student Experience Manager (SEM) Symposium, 4-5 December 2024 6th June 2025

- ‘Hitting the keyboard’ : Exploring student feelings and approaches to developing legal research skills 9th May 2025

- From Feedback to Action: The Student Voice Festival in Law Education 15th April 2025