Law Students and Extra-Curricular Activities in a Time of Pandemic

By Andrew Gilbert and Jessica Giles

This blog arises out of our SCiLAB-funded project, ‘An Exploration of the Use of Extra-Curricular Activities by Law Students and Alumni’, which we carried out during 2020-21. The project aimed to explore Open University (OU) law student engagement in extra-curricular activities (ECAs) and to understand how OU law graduates have used the experience of their ECAs to secure professional-level employment.

We surveyed level 2 (level 5 on the RGF) law students using an online survey and undertook semi-structured interviews with 8 OU law alumni currently in professional legal work or training. Given the timing of the research (early 2021), the impact of the pandemic on law student engagement with ECAs was explored. We also gathered demographic data to better understand differential engagement and outcomes. This report covers the findings of our work with level 2 students. The results of our alumni interviews will be discussed in a later blog.

The online survey

We sent an online survey to 1,046 level 2 law students. 114 completed surveys were received (11% completion rate). The survey asked about time spent engaging in seven types of ECAs, whether engagement has been affected by the pandemic, and motivations for participation in the activities. It also asked about legal work experience, and gathered demographic data about the participants.

Sixty students completed questions asking about their characteristics and backgrounds, showing:

- 73% (n=43) identified as white English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British. Five respondents (8%) identified as black African, black Caribbean or mixed ethnicity.

- 58% (n=34) were female; 42% male (n=25).

- 95% (n=53) were mature students.

- 28% (n=17) indicated some form of enduring health problem or disability.

- In terms of class backgrounds, 52% (n=31) were from professional or managerial origins, 22% (n=13) from intermediate origins and 15% (n=9) from working-class origins.

- 20% (n=12) had been eligible for Free School Meals at some point during their schooling.

This sample of 60 respondents, which was self-selected, was not far from a representative sample overall compared to the 2019-20 OU UG law cohort.

We used the bivariate Pearson correlation to look at the relationship between the general population sample and various participant groups (e.g. women, working-class origin, disabled) to see if a group’s experience is typical of the general sample.1 The confidence with which some statements can be made about the data is limited by the relatively small sample size.

ECA engagement

Of the seven types of ECAs (see Table 1 for list), the most popular were sports, games or exercise (61 respondents), paid employment (54 respondents) and unpaid voluntary work (39 respondents).

In terms of general levels of ECA engagement, there was a strong correlation between the experience of the whole sample and students with the following characteristics: women, men, disabled, free school meals, and mature students. Values for working-class origin (r=0.76) and ethnic minority students (r=0.44) were less strong, which is consistent with the findings of differential engagement in Blasko (2002) and Stuart et al (2011). However, the sample sizes for these two groups are too small to draw safe conclusions from the data and further investigation is needed to establish if the lower levels of engagement with ECAs are true across a bigger sample. Recent evidence from The Sutton Trust (Montacute and Holt-White, 2021) has shown less engagement in some ECAs by working-class students, with a widening gap between those students and middle-class students apparent during the pandemic. Given the known benefits of ECA participation, it is important to ensure as equitable access to them as possible (Winstone et al, 2020).

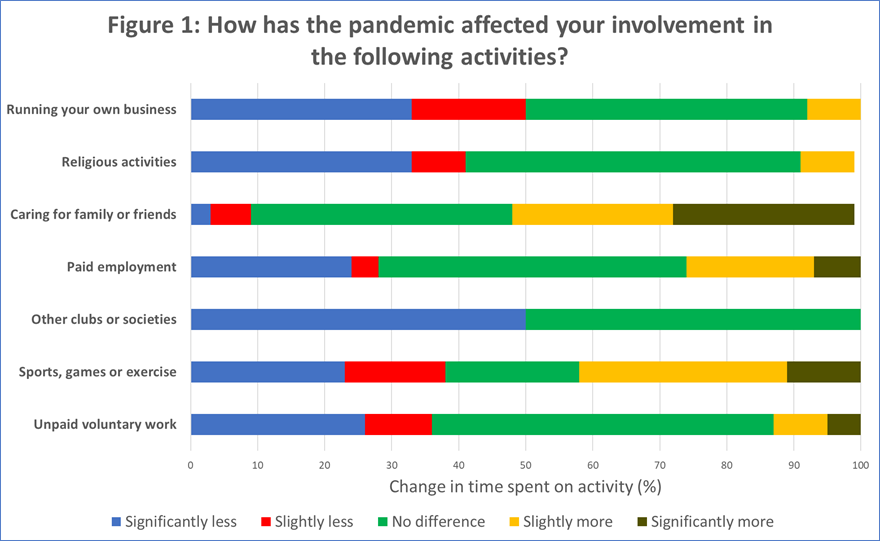

Students were asked to state why they do an activity, selecting as many reasons as relevant from a list of ten. The table below shows the top three reasons selected for each ECA. The results suggest students are altruistic and community minded, as well as being concerned about their own health and wellbeing. Developing skills is also a common theme, but – perhaps surprisingly – enhancing CVs and employability do not feature highly.

Table 1: Top 3 reasons why students undertake each ECA (highest first)

Pandemic impact

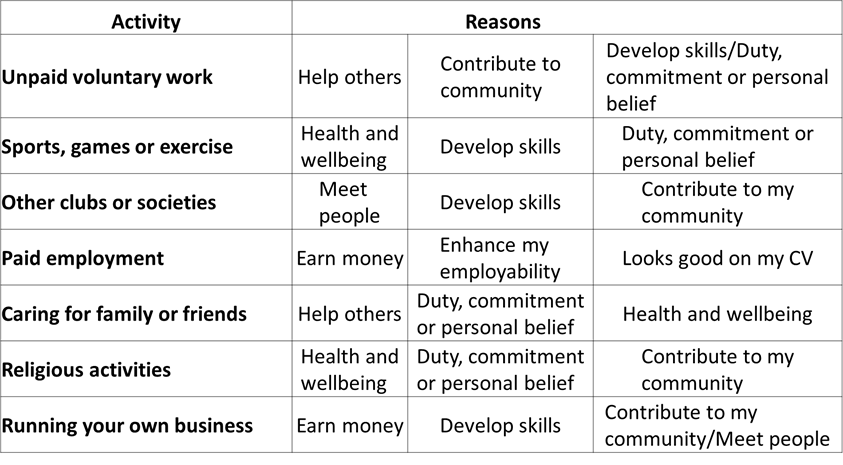

The pandemic did not impact ECA engagement uniformly (Figure 1). Around a quarter of respondents had spent significantly less time doing unpaid voluntary work, paid employment or sports, games or exercise as a result of the pandemic; while a third had spent significantly less time engaging in religious activities or running their own business. Other studies of UK undergraduate students have also reported much lower levels of ECA engagement during the pandemic (Montacute and Holt-White, 2021). By contrast, 27% of OU respondents had spent significantly more time, and a further 24% spending slightly more time, caring for family or friends.

Figure 1: How has the pandemic affected your involvement in the following activities?

Of those doing an activity significantly or slightly less due to the pandemic, working-class origin and ethnic minority students seemed to show the weakest association between the pandemic and a negative impact on their engagement with ECAs, i.e. those students were least adversely affected by the pandemic. However, Montacute and Holt-White (2021) found that working-class students experienced greater falls than middle-class students in the level of their ECA engagement, with the exception of paid work which was unaffected.

It is widely known that caring responsibilities have been significantly affected by the pandemic, with some sources reporting more of an adverse impact on women than on men (United Nations, 2020; Newson, 2021; Pugh, 2021), although not all studies have found this (Aldercotte et al, 2021). Amongst OU law students an increase in time spent caring for family or friends correlates most strongly with the experience of women and less strongly with the experience of other groups. Conversely, our study showed that a positive impact of the pandemic has been more students have spent time doing sport, games or exercise than the number of students who have had such activities curtailed by the pandemic.

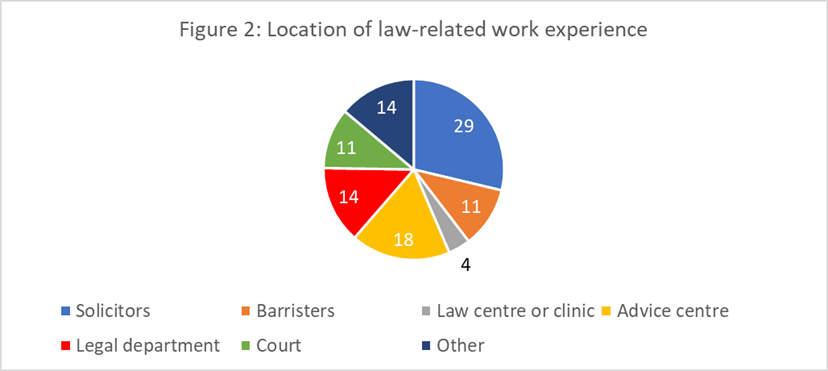

Legal work experience

The responses from students to the question about the period of their legal work experience suggests that many of them who responded affirmatively are working in legal roles already. Nevertheless, a minority of second-year law students had undertaken such experience (39% of respondents). Of those who had legal work experience, it was unpaid for 57% of students. While experience in a solicitors’ firm was the most common, students had a broad range of experience across the justice and legal advice sector (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Location of law-related work experience

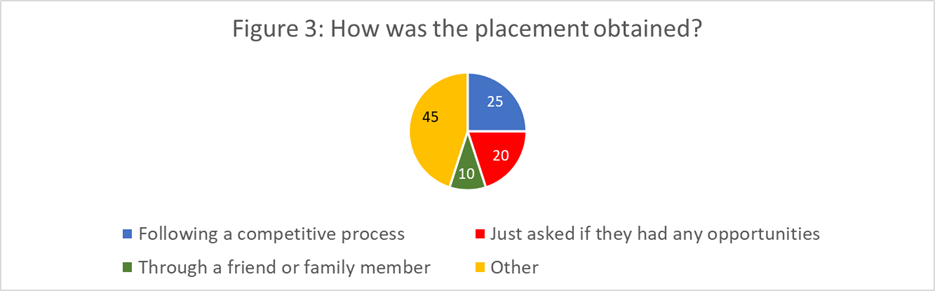

Only 10% of placements had been obtained through a friend or family member (Figure 3). This could be read in two ways, which are not mutually exclusive: students have low levels of social capital or students are successful through other means and have no need to mobilise social networks to obtain work experience.

Figure 3: How was the placement obtained?

Conclusion and next steps

Part 1 of this project has been invaluable for understanding what types of ECAs level 2 students are engaging in and why, as well as how the pandemic has impacted them. The survey revealed that working-class origin and ethnic minority students might be engaging in ECAs less than other groups. Given the unreliable sample size, further work should be done to investigate this. Our data also suggests that students are not primarily seeing ECAs instrumentally in terms of their careers, but as part of a broader project of self-actualisation and altruism. While this broader approach is not to be discouraged, it might imply – in contrast to the strategic approach of alumni successfully working in legal professional roles – that students need further guidance on how best to engage in ECAs during their studies and in particular at an early stage. In addition, they need to learn how best to articulate their experience when seeking employment opportunities. Further thought should also be given to what could be done to remedy any pandemic-induced deficit in preparing for future careers.

Given the value placed on legal work experience in stories of alumni success (see our next blog), it is concerning that only a minority of second-year law students had undertaken such experience. There is cause for optimism though as many students will go on to acquire clinical legal experience in their final year through W360 and some are likely to obtain work experience before they graduate. Our recommendation is, in addition, that it is important to find ways of increasing the numbers of students with legal work experience overall and of enabling students to engage in their career aspirations at an earlier stage in their studies so they can better compete for legal jobs.

Endnotes

1 The bivariate Pearson correlation measures the strength and direction of linear relationships between pairs of continuous variables. The test produces a sample correlation coefficient, r. An r value of -1 is a perfectly negative linear relationship; 0 is no relationship; +1 is a perfectly positive linear relationship; 0.1-0.3 is a small/weak correlation; 0.3 to 0.5 is a medium/moderate correlation; 0.5 to 1 is a large/strong correlation.

References

- Aldercotte, A., Pugh, E., Mcmaster, N. and Kitsell J. (2021) Gender Differences in UK HE Staff Experiences of Remote Working. (Accessed: 18 August 2021).

- Blasko, Z., Brennan, J., Little, B. and Shah, T. (2002) Access to What: Analysis of Factors Determining Graduate Employability. Bristol: HEFCE.

- Montacute, R. and Holt-White, E. (2021) Covid-19 and the University Experience. (Accessed: 25 February 2021).

- Newson, N. (2021) Covid-19: Empowering women in the recovery from the impact of the pandemic. (Accessed: 25 August 2021).

- Pugh, E. (2021) Building Back Better for Gender Equality in Higher Education. (Accessed: 7 September 2021).

- Stuart, M., Lido, C., Morgan, J. and May, S. (2011) ‘The Impact of Engagement with Extracurricular Activities on the Student Experience and Graduate Outcomes for Widening Participation Populations’, Active Learning in Higher Education, 12 (3), pp. 203-215.

- United Nations (2020) The Impact of COVID-19 on Women. (Accessed: 25 August 2021).

- Winstone, N., Balloo, K., Gravett, K., Jacobs, D. and Keen, H. (2020) ‘Who Stands to Benefit? Wellbeing, Belonging and Challenges to Equity in Engagement in Extra-Curricular Activities at University’, Active Learning in Higher Education, pp. 1-16.

This blog represents the views of the individuals, not SCiLAB or the Open University.

Andrew Gilbert

Andrew is interested in the broad spectrum of academic and vocational legal education. He leads the law school’s Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE) curriculum development work and has blogged on why the SQE can’t guarantee competent solicitors and law schools’ responses to the SQE. Andrew is a member of the Executive Committee of the Association of Law Teachers and a peer reviewer for the leading legal education journal, The Law Teacher.

Jessica Giles

Jessica is a Law Lecturer, SFHEA and Barrister. She is Director of the Project on Interdisciplinary Law and Religion Studies at the OU. She is a valued member of the SCiLAB working group representing the Law School.

Blog posts

- Rethinking Tuition: Reflections from the Staff Tutor / Student Experience Manager (SEM) Symposium, 4-5 December 2024 6th June 2025

- ‘Hitting the keyboard’ : Exploring student feelings and approaches to developing legal research skills 9th May 2025

- From Feedback to Action: The Student Voice Festival in Law Education 15th April 2025